‘In the sun’: St. Louis radioactive waste activists find hope in new federal law

After years of mourning family and friends who succumbed to aggressive cancers, activists in Missouri finally won federal recognition that radiation released during the development of nuclear weapons is to blame.

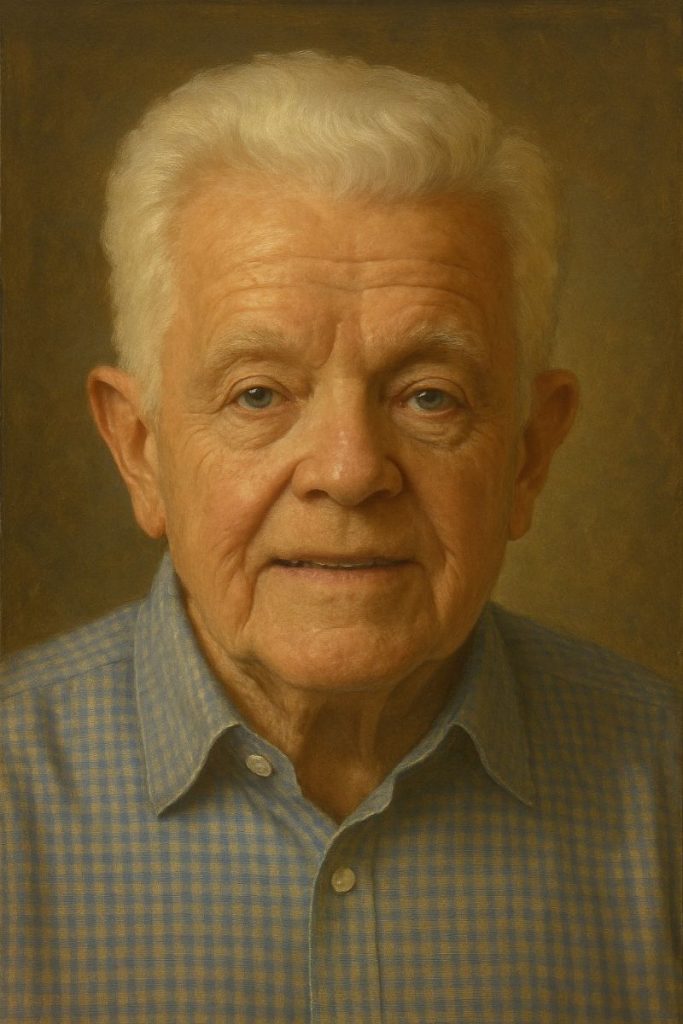

Since the publication of a six-month investigation by The Missouri Independent, MuckRock and The Associated Press, Republican U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley has pressed for Missourians to be included among the states where residents are eligible for compensation. The provision extending help to the St. Louis region, where uranium was processed for the first atomic bombs, New Mexico, where the first bombs were produced and tested, and six other states, was finally included in the massive budget reconciliation bill signed Friday by President Donald Trump.

“We blinked and after 13 years of being in the dark, we were in the sun,” Dawn Chapman, co-founder of Just Moms STL, said in an interview with The Independent.

Records reveal 75 years of government downplaying, ignoring risks of St. Louis radioactive waste

The passage was celebrated as a victory in a news conference in a St. Louis County park adjacent to Coldwater Creek, contaminated by radioactive waste since 1949.

Hawley and Chapman were joined by Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren and activists from around the country to get the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act renewed and expanded. The law, originally passed in 1990, lapsed in 2024.

“It’s a tremendous privilege to be with these heroes who are beside me and behind me,” Hawley said as he opened the news conference.

The people who lived in the areas now eligible for compensation have waited far too long for help, Hawley said.

“The truth is, it wasn’t just the people of Missouri who had waited for 70 years to have justice done,” Hawley said. “It was the people of the Navajo Nation. It was the people of Utah, it was the people of New Mexico, it was the people of Idaho, it was the uranium miners and atomic veterans from all over the country who had been waiting for decades for the federal government to finally own up to what it had done.”

The Navajo Nation has suffered from fallout swept by winds onto its Arizona lands from nuclear weapons tests, Nygren said. More than 100 uranium mines were on reservation land and, in 1979, the Church Rock Spill, the largest release of radioactive material in U.S. history, poured 94 million gallons of radioactive waste into the Puerco River.

“People were devastated because their livestock, their cattle, their land, their water resources were extremely affected,” Nygren said.

Under the provisions included in the budget bill, Missourians who contracted one of 20 cancers, including lung or breast cancer, after living in any of 21 zip codes for at least two years are eligible for compensation. Leukemia is also covered, but only if it occurred at least 20 years after residence in the designated areas.

In addition to Missouri, the budget bill allows compensation for radiation exposure related to the Manhattan Project in 14 zip codes in Tennessee, two zip codes in Alaska and three in Kentucky. New Mexico is included among the states where fallout spreading downwind from atomic and nuclear tests contaminated the land. The downwind areas, in Arizona, Nevada and Utah in the original compensation act, now include New Mexico, Colorado, Idaho and Montana.

Missouri is also working to identify if other areas are contaminated.

During this year’s legislative session, Missouri lawmakers passed a bill expanding the state’s ability to find radioactive contamination in the St. Louis region. The measure, which Gov. Mike Kehoe has indicated he will sign Thursday, would authorize the Department of Natural Resources to seek a search warrant to conduct investigations on otherwise off-limits government land and removes a $150,000 annual cap on how much the state can spend on an investigation.

The celebration of the bill’s passage is clouded by the memories of people who died without compensation or acknowledgement that nuclear material caused their deaths, Chapman said at the news conference.

“The hard thing today, and why it’s so heavy, is there’s so many people that should be behind us, that have already passed on,” she said. “There’s many people from the Navajo nation that have passed on, that were part of this fight, that are not here to be recognized.Our government made it harder. They did everything they could to hide the truth from us.”

The compensation can cover medical costs for people who are still alive, or they can elect to receive a single payment of $50,000. Family members of people who died of one of the listed cancers are eligible for a one-time payment of $25,000, to be divided equally among the living heirs.

The compensation for people who lived downwind of nuclear tests or worked in uranium mining was increased to $100,000.

The money will help people pay for treatments and expenses not usually covered by insurance, Chapman said.

“When you look at this list of cancers, and you look at the cancers that people are getting in North County, they’re horribly aggressive,” she said. “And we have great hospitals and cancer centers here, but what we do not have is the ability for a mom who’s already used up all of her parental leave, her family medical leave, to take extra time off with her child.’

The new federal legislation sets the starting date for possible exposure at 1949, a key date uncovered in the joint investigation by The Independent and its reporting partners.

Giving The Independent access to the documents obtained through years of federal Freedom of Information Act requests was “one of the scariest, riskiest things that we did, and it is the thing that ended up paying off the most,” Chapman said. “It is the thing that launched RECA, when Sen. Hawley read the story and saw the documents that you guys put up.”

The documents showed that during the war, Mallinckrodt Chemical Works processed uranium for the Manhattan Project, the name given to the effort to build the bomb, in downtown St. Louis. Uranium from the Mallinckrodt plant was used in the first sustained nuclear reaction in Chicago, a significant breakthrough.

An internal Mallinckrodt memo from 1949 shows the company was storing highly radioactive residue called K-65 in deteriorating steel drums at the St. Louis airport near Coldwater Creek. The material was so dangerous, the memo said, that Mallinckrodt couldn’t simply put it in new containers because “the hazards to the workers involved in such an occupation would be considerable.”

Efforts to find a buyer for the waste resulted in a sale in 1965, and within a few years, most of the waste was sold and moved just up the road to a site on Latty Avenue in Hazelwood where it, again, sat exposed to the elements and adjacent to Coldwater Creek.

In early 2024, more than 70 years after workers first realized barrels of radioactive waste risked contaminating Coldwater Creek, the federal government put up signs warning residents. Cleaning up the creek carries a cost estimated at $400 million.

“We are here today in the very park that made me sick,” said Karen Nickel, a co-founder of Just Moms STL. “I grew up on that street right there, a place where I played as a child, never knowing the danger from radioactive atomic bomb waste.”

Nickel has lupus and other auto-immune diseases she believes were caused by the radiation but her illnesses are not covered in the compensation act expansion. She doesn’t regret the hard work, even if it won’t help her, she said.

“I feel like the little girl who got sick here didn’t suffer in vain,” Nickel said. “This moment is bittersweet. It’s victory wrapped in grief. But I also hope that no other community has to wait this long to be heard.”

The waste was spread by efforts to remove it. After extracting valuable metals from the bomb waste, the buyer, Cotter Corp. initially received permission to use a pit at the Weldon Spring quarry in St. Charles County, which was already a disposal site for other radioactive waste.

After that decision was reversed over concerns that radiation was already leaking from the quarry, over a period of 2 ½ months in the summer and fall of 1973, Cotter took the problem into its own hands, without telling government regulators.

The company mixed the radioactive waste with tens of thousands of tons of contaminated soil from the site and illegally dumped it in a free, public landfill called West Lake, under three feet of soil and other garbage.

The landfill was declared a federal toxic Superfund site in 1990. In 2010, a subsurface smoldering event, similar to an underground fire, at the Bridgeton Landfill threatened the radioactive waste buried in the since-closed Westlake Landfill nearby. That fire sent noxious and hazardous fumes into surrounding neighborhoods. The company in charge of the Bridgeton Landfill now spends millions a year to contain it.

At the news conference, activists from across the country who lost family members told a part of their story and their fight for recognition and compensation.

Maggie Billiman, whose father Howard Billiman was a Navajo code talker in World War II, said her family lives downwind from where 100 nuclear weapons were tested. He died of stomach cancer in 2001.

“When we heard RECA was passed, we cried for happiness,” Billiman said.

Sherrie Hanna of Prescott, Arizona, said she lost both her husband and her father to cancer and received compensation under the act before it expired in 2024. She was worried it would not be renewed, Hanna said.

“For many of us downwinders, myself included, the question is not if we will receive a cancer diagnosis but when,” Hanna said.

To get the renewal and expansion passed, Hawley said he had to overcome resistance among Republicans to new federal spending and find legislation that had to pass to carry it.

“It happened because it’s justice,” Hawley said. “But there’s more to do.”

This article was updated at 3:40 p.m. to correct the day the federal budget bill was signed.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Missouri Independent is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Missouri Independent maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jason Hancock for questions: info@missouriindependent.com.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.