Something about Mary

When Mary Griffith said goodbye Friday, it marked the end of a 45-year broadcasting career — and the close of a 77-year Griffith family legacy of delivering the news in the Tri-States.

That’s right. Seventy. Seven. Years. Between her father, the late Charlie Griffith, and Mary herself, there’s hardly been a local newscast that didn’t have a Griffith behind the mic. And now? Mary’s stepping away from WTAD-AM not because she’s ready to retire, but because life — and love — said it was time. Her husband, Greg, is battling kidney failure and has begun home dialysis. So, she’s trading studio headphones for sterile gloves and talk segments for treatment schedules.

But don’t expect her to go quietly.

Griffith, who’s practically part of Quincy’s auditory wallpaper, started her career in the early ’80s — a time when you could get a Budweiser at the Boat Club for under a dollar and newsrooms still had ashtrays. She didn’t plan on being a broadcaster. In fact, she wanted to be the next Woodward or Bernstein, pounding out Pulitzer-worthy prose for a big city newspaper. But a job offer at WGEM TV changed all that. So did the fact that the “new hire” her dad was complaining about training — was her.

Charlie came home one Friday grumbling about having to train “some damn new kid” at work the next morning. “They won’t know a damn thing and they’ll probably only stay six months,” he muttered. Mary kept her poker face. The next morning in the kitchen, just before their carpool commute, she let it drop: “Dad, I’m the new girl.” He was stunned. Furious, even. Begrudgingly, he drove her to the station anyway. It was an awkward ride to work — and the start of a career that would eventually outlast everyone in that newsroom.

Her first words on the radio weren’t about politics or policy. They were, “Daddy, I have to go potty.” As a kid, Mary tagged along with her dad to the station, where she passed the time spinning empty record turntables and creating terrifying fake forecasts on the weather set with every plastic tornado decal she could find. One day, she told another little girl who was hanging out at the station, “You can play, but you can’t have the tornadoes. You can have the sunshine.” Turns out the girl was Mary Oakley — daughter of WGEM’s CEO. Oops.

She eventually made her way onto weekend television, filling in as needed, until she applied for a permanent anchor role. She didn’t get it. Not because of her voice. Not because of her reporting. But because, in the words of her news director, she “wasn’t pretty enough.” Mary’s response? “I look exactly like your 6 o’clock anchor — and he’s 35 years older than me.”

So, she left.

She walked out of the WGEM building and straight into radio — first at KHMO-AM in Hannibal, then KGRC-FM (also in Hannibal at the time), and eventually WTAD, where her name became synonymous with local journalism, tough questions, and the kind of storytelling that made both mayors and moms sit up and listen.

But there was another pivotal role she held: Babysitter.

Mary aka “Aunt Pinky” used to babysit for yours truly. And yes — she survived that too. Barely. She told me I was sweet, curious, occasionally wild, and always convincing her that I had permission – even when it came to giving my brother a mohawk.

She also reminded me of something else: she and my dad were close — both in the newsroom and outside of it. They worked side by side for decades and treated each other like family. Mary was more than a colleague; she was an extension of our crew. A fixture. A favorite. And honestly, a total pro — even when babysitting turned into a full-blown Adventures in Babysitting sequel starring a small child with the energy of a Jack Russell terrier and the negotiation skills of a hostage negotiator.

There were highs. Like covering the Super Bowl in 1981. And there were hilariously low-budget newsroom schemes — like the time she found out WGEM Sports Director Rich Gould had been bumming quarters off her and the other rookies at the station. “I really need a soda,” he’d say. “Can I borrow a quarter?” Mary obliged, again and again, until she discovered where those quarters were going: a jar in his desk drawer labeled “honeymoon fund.” She didn’t ask for her money back. But she made sure he knew she knew.

And then there were the hard lessons.

One of Mary’s early big wins came when she won “Best Investigative Reporting” from the Missouri Broadcasters Association for a series on housing conditions for low-income families in Hannibal. It was a proud moment — until she realized what had happened in the aftermath. The city condemned all the properties she featured in her exposé. Sounds like a win, until you think about it: no one built replacements. No one offered help. The families living in those “unacceptable” homes had nowhere to go.

“I didn’t invite them to come live with me,” she said. “I didn’t think far enough ahead. I told the story, but I didn’t ask the next question: What happens to them now?”

It was a turning point — a sharp reminder that the job isn’t just about truth. It’s about impact. And it shaped how she approached stories moving forward. With more care. More curiosity. More conscience.

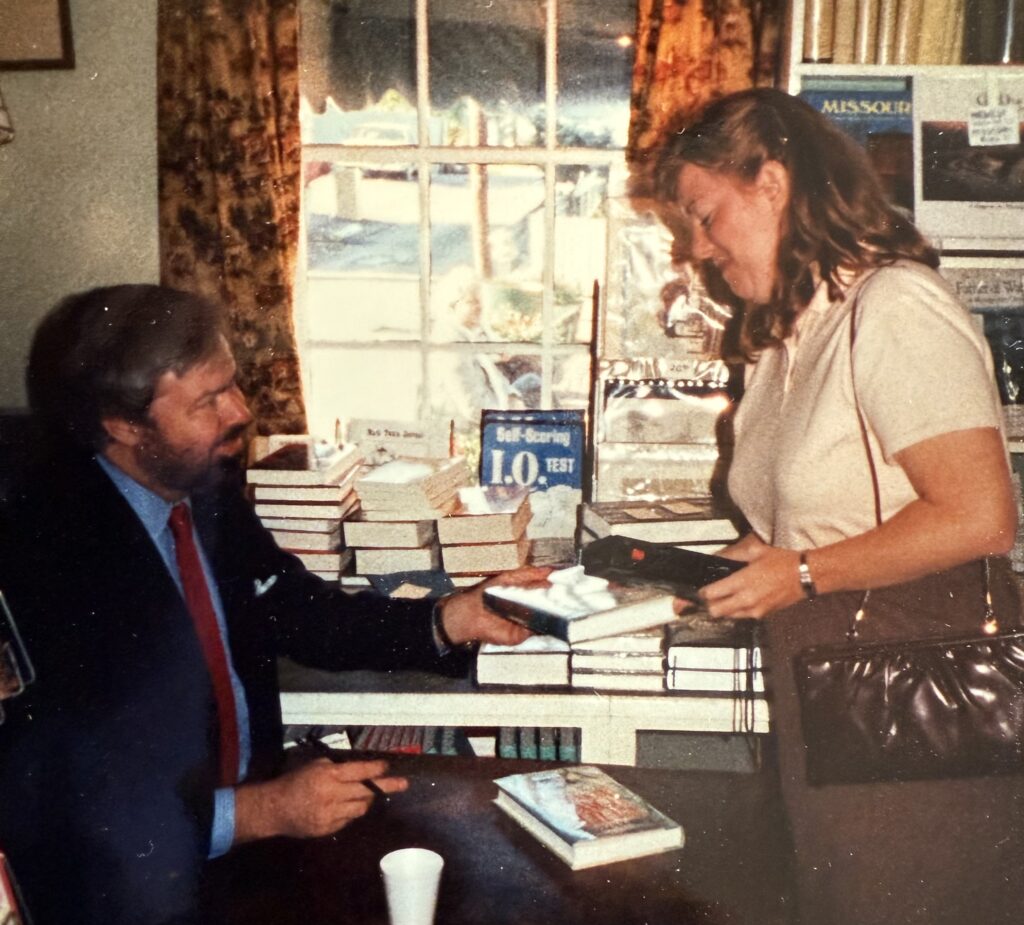

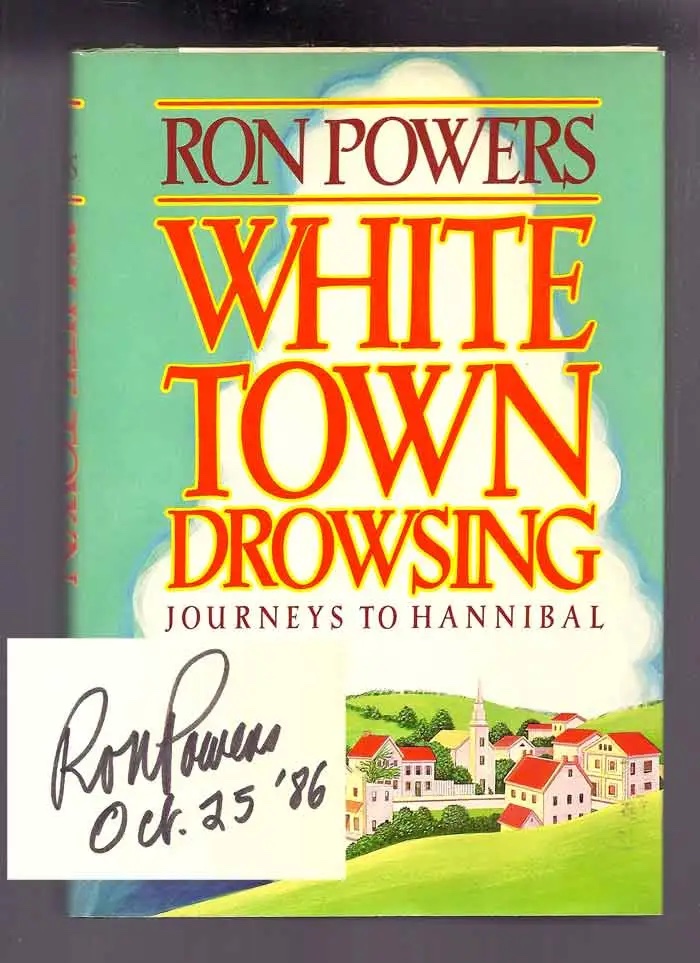

She kept digging, even when it made people uncomfortable — especially during a financial scandal involving Hannibal’s sesquicentennial celebration in 1985. Her relentless coverage caught the attention of Pulitzer Prize-winning author and Hannibal native Ron Powers. He not only interviewed Mary for his book, White Town Drowsing, he wrote her in as a character.

“To Mary, one of the real heroines of this book and a journalist I admire,” he inscribed in her copy.

By 1988, WTAD came calling, and it would become her home for the next 37 years.

Mary started out doing afternoon news and beat reporting, eventually working mornings alongside Jeff Dorsey. And then eventually with the great Steve Boll. She covered floods, school board and city council dramas (some things never change), and just about every local controversy you could name. And when things got hot — when advertisers complained or politicians got twitchy — Mary sometimes found herself temporarily ousted. Twice she was fired. Twice she was asked back.

She stuck around — not just in spite of the turbulence, but because of it.

And in that time, Mary became more than a journalist. She became part of the town’s collective memory. She was the voice in your kitchen, the question at your press conference, the calm during the storm — and occasionally the storm itself.

Even when the criticism came hard (and it did — entire Facebook pages have been dedicated to hating her), Mary never let it shape her. Mostly because she never saw it. She’s never had a Facebook page. Still doesn’t want one.

“I don’t care what someone ate for dinner,” she shrugged. “And I really don’t care what they think about something they know nothing about.”

She’s been called too bold, too opinionated, too much. One woman even called the station to say, “Your father would be so disappointed in you.” Mary’s response? “I don’t remember you having dinner at our house. But I had thousands with my father — and I can assure you; he was proud of me.”

That was Mary. Clear-eyed. Sharp-tongued when necessary. But always guided by conviction, not convenience.

And still, she kept showing up. Kept asking. Kept telling the stories.

“I’ve had presidents on the mic,” she said. “But the interviews I remember most are the everyday people who did something extraordinary.”

A mother who survived a near-death childbirth and became an advocate for blood donation. A kid with unshakable curiosity. A neighbor who stood up when no one else would. These are the stories that stuck with Mary. Not because they made headlines — but because they made a difference.

Because to Mary, journalism was never just about breaking news. It was about breaking cycles. Asking questions others were too afraid to ask. Telling stories others tried to bury. Holding people — and power — accountable. Whether it was city hall, a school board, or a shady sesquicentennial committee, Mary understood that a healthy community needs a watchdog with a microphone.

And for 45 years, she was that voice.

“I’ve stuck in when I didn’t like my job. I’ve stuck in when people didn’t like me,” she said.

“It’s kind of like Survivor. I’ve outwitted, outlasted, outplayed.”

And through it all — she never stopped showing up.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.