Firings, corruption accusations create turmoil at struggling Scotland County Hospital; CEO fired, pharmacy closed, leaving cloud of suspicion

MEMPHIS, Missouri – Joni Lloyd was in her pajamas when the call came.

Lori Fulk, chair of the Scotland County Hospital District Board of Directors, was calling. She asked Lloyd, the vice-chair, to come to her house to talk.

When Lloyd arrived the evening of Aug. 15, she found Fulk was not alone. An emergency board meeting was underway, called without public notice. Two of the six board members, Bob Neese and Joe Doubet, were deliberately excluded.

The others on hand were board members Nic Hatfield and Travis Trueblood; Meagan Weber and Brent Pierick, at the time newly selected to share the title chief operating officer; and Achim Hoyal, listed in the minutes as a consultant.

“That evening, a vast conspiracy was laid out,” Lloyd said shortly before resigning during a Sept. 27 board meeting.

Lloyd declined a request for an interview for this story. Her account is taken from a video of the Sept. 27 meeting published by the Memphis Democrat and descriptions in a Sunshine Law complaint to the Missouri Attorney General’s office.

“I was manipulated, threatened and made to fear by words that were spoken,” Lloyd wrote in her complaint.

The closed meeting minutes for Aug. 15 report the board received a financial report “with concerns of malicious impropriety and content.” The four members present voted to fire Dr. Randy Tobler, the hospital’s CEO since 2014, and Michael Brandon, the chief financial officer, who would be “walked out and terminated and all access rescinded.”

In an interview, Doubet said before he’d even been officially informed Tobler was fired he overheard gossip about “$16 million that Dr. Tobler had apparently embezzled.”

Brandon said his wife heard gossip “that Dr. Tobler and I had been arrested by the FBI, which was completely untrue.”

Neither Tobler nor Brandon has been criminally charged.

The board and hospital executives are under pressure to save the financially troubled 25-bed hospital, which has lost money in each of the past five years. The hospital is a primary source of care for a five-county region, where it operates three outpatient clinics in addition to its inpatient facility, and an audit in March warned it may fail.

For the past two months, The Independent has investigated the turmoil, accusations of financial wrongdoing and possible criminal inquiries at the critical access hospital. Details of the tumult were revealed through Sunshine Law requests, interviews with people inside and outside the hospital and the reporting of the local newspaper, the Memphis Democrat.

Weber, who was named CEO after Tobler was fired, initiated the criminal investigations within days of Tobler’s ouster. Records provided under a Sunshine Law request show she used an online system to file a complaint about health care fraud with the Office of Inspector General in the Department of Health and Senior Services.

In an email to The Independent, she said she called the FBI and an agent was sent to interview her.

“They recommended a forensic audit at this time, and will not move forward with us until that is completed,” Weber wrote.

Sunshine requests have not produced any documents that specify what auditors are reviewing.

Fulk, Weber and Hoyal declined requests for interviews.

In a statement she read at the Aug. 30 board meeting, Fulk said she believed did what she thought was needed “after being presented information showing some financial irregularities.”

She said she could not give specifics because of legal concerns.

“We want to assure the public that the steps necessary are being taken to protect this facility,” Fulk said.

Brandon, in an interview, said he has never been told why he was fired.

“That would be something that would be very nice to know,” he said.

Tobler provided a statement to The Independent but declined a request for an interview.

“The citizens of Scotland County deserve to know what is happening at Scotland County Hospital,” Tobler said. “I intend to cooperate with any investigations that occur, and do all in my power to promote transparency and obtain justice.”

Hospital politics

Scotland County Hospital was created in 1970 under Missouri’s hospital district law. It is governed by six directors, elected from districts in Scotland County.

It is a critical access hospital, a designation under federal law intended to support vital health services in rural areas. Hospitals receive cost reimbursement from Medicare and access to discounted drugs for outpatient prescription services.

The hospital serves a population of about 12,300 in five counties.

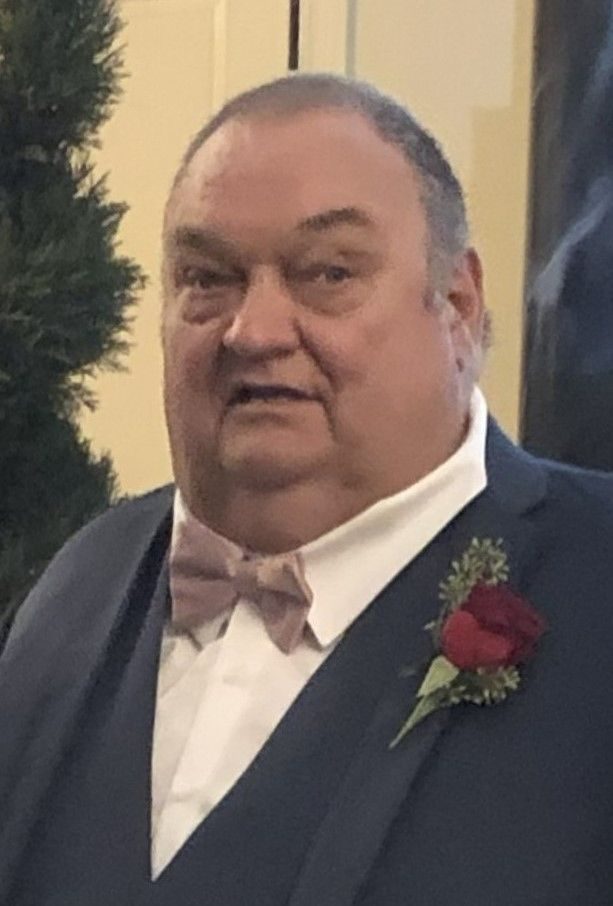

Tobler, an obstetrician/gynecologist practicing at the hospital since 2006, became chief executive officer in 2014. He replaced Marcia Dial, who had held the position for 26 years.

His ouster upset an orderly transition. In March, Tobler submitted his resignation, effective Sept. 3. Weber and Pierick were to take over administration as joint operating officers.

In the days following the Aug. 15 meeting, things moved rapidly.

At the hospital’s request, on Aug. 16 the Missouri State Highway Patrol dispatched a trooper to be at the hospital until Tobler and Brandon were off the premises, said Cpl. Justin Dunn, spokesman for Troop B.

“Due to the fact that they were terminating an employee or associate of the hospital, they requested our presence to be nearby just in case law enforcement was needed,” he said.

Brandon said the trooper, as well as a Memphis Police Department officer, was present in the room when he met with Fulk. He was not allowed to gather his own personal belongings before he left, he said.

Tobler met with Fulk and Lloyd in the afternoon. And the board met again, this time with Neese and Doubet notified, that evening.

Doubet and Neese, in interviews, said they were initially told they were excluded from the Aug. 15 meeting for their own protection. Neese said he was later accused by Fulk and Hoyal of being involved with Tobler’s dealings.

He was also accused of personally benefiting from a hospital land deal. Neese denied profiting from the deal, where he was authorized to bid on behalf of the hospital by the previous CEO, Dial, on a parcel up for auction.

Hoyal took center stage at the next board meeting, Doubet said, though he says he didn’t know who Hoyal was when he arrived.

Since it was a closed meeting, convened on seven-hours notice, there was no audience. So the presence of someone who wasn’t a board member or employee of the hospital was odd.

Doubet introduced himself.

“I said ‘Hello.’ I said ‘My name is Joe Doubet. I am the secretary of the board.

“And he said ‘I’m the fixer.’ And I said ‘the fixer? What are you going to fix?’ He said, ‘I don’t know, but when I find it, I’m going to fix it.’”

From that flip answer, Hoyal presented the full board with the accusations made the previous night.

“He said ‘this is the most negligent, incompetent board I’ve ever seen,’” Doubet said.

There was a third board meeting that week, the regularly scheduled monthly meeting.

On the minutes of board meetings for Aug. 15, 16 and 18, Hoyal is listed as a consultant.

By the next week, Hoyal was the hospital’s interim financial officer. In response to Sunshine requests, Weber wrote that the hospital had no records Hoyal was employed before being named interim chief financial officer on Aug. 24. The hospital records show no payments to Hoyal as a consultant, Weber wrote.

Neese and Doubet said they have tried, and failed, to find out who authorized Hoyal to look at hospital financial records. The board never voted to engage him as a consultant, they said.

The basic charge Hoyal made, Neese said, was that Tobler had surreptitiously obtained ownership of an entity called Memphis Community Pharmacy. Opened in 2019, proceeds above costs were supposed to go to the Scotland County Hospital Foundation, created at the same time.

Intended to help the hospital capture drug discounts under federal law, Hoyal alleged that $16 million couldn’t be accounted for.

The pharmacy was closed on Aug. 17. Documents on file with the Missouri Secretary of State’s office show the pharmacy was owned by a corporation controlled by the hospital board.

The pharmacy never produced enough revenue to divert $16 million, Brandon said. All the revenues are recorded in the hospital’s financial statements, he said.

“To me it is absurd that number is being thrown around,” Brandon said.

The story told by Hoyal and Fulk at the Aug. 15 and 16 meetings went far beyond accusing Tobler of misconduct. The “vast conspiracy” described by Fulk, Lloyd said, included Tobler and Neese as well as the hospital’s long-time law firm, its long-time auditor and state Sen. Cindy O’Laughlin.

Fulk included O’Laughlin in the circle of conspiracy by alleging the foundation, a not-for-profit forbidden by federal law from engaging in political activities, donated $50,000 to her campaign fund.

“That was false,” Lloyd said, facing where Fulk could be seen on a remote camera attending the Sept. 27 meeting from home.

O’Laughlin, a Republican, was elected to the Missouri Senate in November 2018, about six weeks before the foundation was created. Her reports to the Missouri Ethics Commission do not show any contributions from the foundation and there is a limit of $2,400 on any single donation.

IRS filings show net assets of $159,000 in the foundation on June 30, 2020, with $7,229 in cash expenses for the year.

“This is the craziest thing you’ve ever seen,” O’Laughlin, who will serve as majority leader of the state Senate next year, said in an interview with The Independent.

There is not even a kernel of truth in the allegation, she said. Her family owns a trucking and concrete company and it has never done business with the hospital or any associated entity.

“I don’t know why I am even in it,” she said.

After convincing the board to dump Tobler, Hoyal next took up the task of convincing them to hire him as chief financial officer. Hoyal presented his resume and demands for employment at the Aug. 18 meeting.

The resume showed a bachelor’s degree in accounting earned over eight years from Western Governors University, an online college. Some of his written demands included:

- A seven-year contract paying $175,000 annually, automatically adjusted for inflation, plus a $100,000 tax-paid bonus.

- Ownership of a 12-acre lot, owned by and adjacent to the hospital, with construction to rebuild two houses with amenities like hot tubs, an enclosed barbecue patio, and garages with room for seven cars.

- Give his father, Dr. Neil Hoyal, a $100,000 bonus and a $30,000 annual raise.

The final contract signed Sept. 30 gives Hoyal a $200,000 annual salary – $60,000 per year more than Weber, the CEO – but no automatic inflation adjustment.

It is almost double the salary Brandon received for the same position.

Hoyal interviewed at one time for a position as a revenue cycle manager but was not hired, Brandon said.

Brandon’s salary, $103,000 a year, was based on a survey of executive pay at similar-sized hospitals. It was set at the 25th percentile of the range found by the survey, meaning three-fourths of hospital financial officers were paid more. The 75th percentile amount was $175,000 per year, he said.

“Paying $200,000 seems like a stretch,” Brandon said.

Hoyal did get a seven-year term, two years longer than Weber and six years more than Pierick is guaranteed. And he received better job protection.

Both Weber and Pierick can be terminated with 90 days notice for no reason. Hoyal’s contract states he can be fired “if and only if by conviction of a misdemeanor or felony.”

Michael Harris, a St. Louis attorney specializing in employment law, said the clause is “of little value” because of the lengthy time between criminal charges being filed and a conviction.

Most contracts for executives include provisions allowing termination for a variety of causes, Harris said.

“They used to call them bad-boy clauses,” Harris said, “though that is probably not politically correct any more.”

One way to state it generally is “conduct that is materially detrimental to the organization,” he said. “It is kind of a catch-all so if someone does something really stupid, or really wrong, you have to have the ability to sever ties.”

Another hole in the contract, Harris said, is the severance clause. It is almost impossible to understand, he said, and paying a buy-out doesn’t release the hospital from any other claims Hoyal may pursue in court.

“The organization is very thinly protected against the CFO’s misconduct in this case,” Harris said.

Before presenting his demands, Doubet and Lloyd said Hoyal called them.

“He talked a little bit and he told me, ‘if you have my back, and my people’s back, then I’ll have your back. You know how this works,’” Doubet said. “He said, ‘time is of the essence. The government is coming in here and freezing all your assets. And you’re going down for this unless you let me help you out.”

During the Sept. 27 board meeting, Lloyd accused Fulk of giving Hoyal her number.

“Giving him board members’ cell numbers so that he could threaten us is unethical and egregious,” Lloyd said.

Reached by phone, Hoyal said he could not respond.

“At this time, I am unable to talk about it, per the lawyers,” Hoyal said. “I don’t want to say anything that would get me in trouble.”

His father, however, had plenty to say after Neese, Lloyd and Doubet spoke at the Sept. 27 meeting.

Dr. Neil Hoyal said all his son did was point out a problem and he has been “libeled and slandered” in return.

“I resent your accusations against my son because I happen to know his motives are pure, regardless of what you think,” Neil Hoyal said. “You have something to hide, and that’s the problem.

Aftermath

The turmoil caused by Tobler’s ouster caused the biggest shakeup on the board in decades.

And it will test whether Doubet was right when he wrote he was resigning, in part, because of the “lack of outrage in this community over the fact that a person can lose their job over an allegation…”

Next April, four of the board’s six seats will be up for election. One seat will be for a full six-year term, the others to fill out the remaining years on the terms of resigned members.

Voters won’t see candidates on the ballot, however, unless two or more candidates file. State law allows local political subdivisions to avoid the cost of an election when only one candidate files.

At its meeting Oct. 25, the board ditched a plan to convert from district to at-large elections before April’s vote. With the board members angry over Tobler’s departure now out of office, the idea was dropped.

“Now that we have a full board and a willing board we don’t feel like it is as urgent a situation as a few months ago,” Weber said during the meeting.

In a joint interview, Neese and Doubet said the ouster of Tobler was the culmination of a scheme plotted by Fulk.

After the Aug. 16 meeting, where he first heard the accusations against Tobler, Doubet said he and Lloyd were chatting with Fulk in the hospital parking lot.

“She stated that she’s been trying to get rid of Tobler for six years and she finally accomplished it,” Doubet siad.

She gave no indication that she was unhappy with Tobler prior to his firing, Doubet said.

“It’d be different if you see tension all the time, or you know, argumentative stuff but there was nothing,” he said.

Soon after, Lloyd, Neese and Doubet took the unusual step of reporting their own board to the Attorney General’s Office for Sunshine Law violations. So did Echo Menges, editor of the Memphis Democrat and chair of the Missouri Sunshine Coalition.

Neese reported “our entire hospital is being jeopardized by the actions of a few rogue board members, an outsider, Achim Hoyal, who has made outlandish allegations and demands, and the supposed new CEO, Meagan Weber, who has fully bought into what appears to be a con and is now a coup.”

On Sept. 18, the hospital’s attorney received a letter from Jason Lewis, chief counsel for governmental affairs with the attorney general’s office. It said the attorney general was investigating the complaints about the board’s Aug. 15 meeting.

“Our review of this meeting and its aftermath continues,” Lewis wrote.

The letter made several demands – including “cease holding meetings that do not include all board members” and that the board attend a Sunshine Law training session by the office within 60 days.

Fulk has tried to defend the board’s actions. Speaking on the phone, she said she cannot talk in detail because board attorneys have warned her to remain silent.

“What they chose to comment on, I can’t speak to,” Fulk said. “There will come a time when hopefully I can.”

Neese, speaking Sept. 27, said the accusations against Tobler and others had “murdered careers and reputations.”

“May God have mercy,” Neese said, “because I don’t believe the lawyers will.”

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.