‘I had never seen anything like it before’: Fifty years later, memories of the flood of 1973 remain vivid

QUINCY — When Norman Haerr thinks back to the great flood of 1973, he will always believe it served as a reminder.

“The Lord was letting us know that he’s in charge,” Haerr, a resident of Taylor Mo., said.

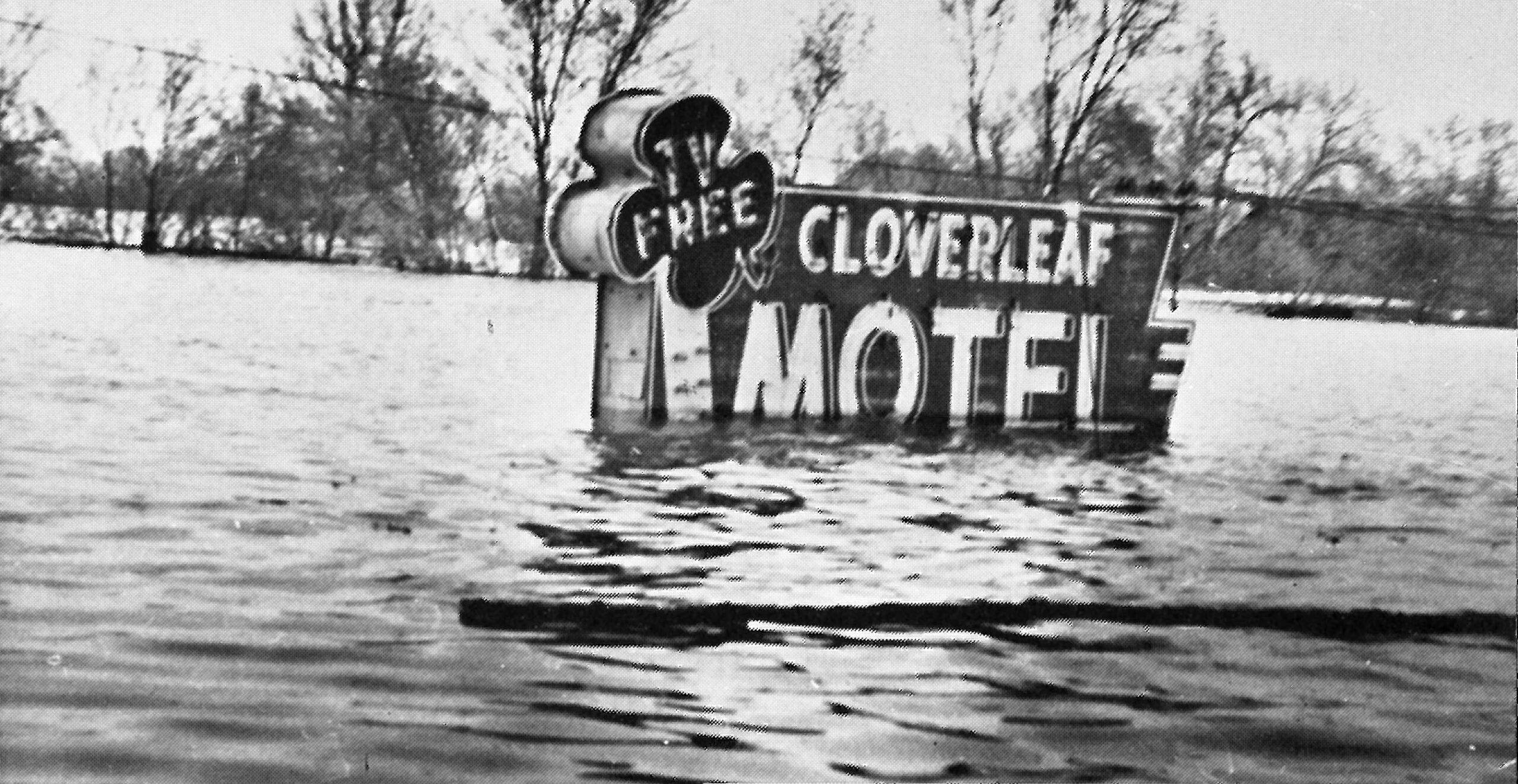

This spring marks the 50th anniversary of the devastating event that saw the Mississippi River overflow its banks and cover 15,000 acres in north central Missouri alone — including West Quincy, where many of the buildings were completely covered by the floodwaters.

Haerr said heavy rains led to the flooding, and there was not ample time to prepare for the worst.

“The water had to go somewhere,” said Bill Hofmeister of Quincy, who at the time also lived near Taylor “in the flood plain.”

Hofmeister said the situation took a turn for the worst on Easter weekend. By the Monday after, the entire region was in distress.

“The levees could not hold the water back,” he said.

The river was at flood stage for 93 days, West Quincy was in shambles, and for a period, there was no bridge crossing available between Keokuk, Iowa, and St. Louis.

Haerr, who would later serve as president of the Fabius River Levee and Drainage District, said levees in the region dated to before 1920 and had been able to hold the Mississippi waters back — until 1973.

Calvin Kentfield, who grew up in Keokuk, wrote for the New York Times in July 1973: “The Mississippi was an active, ever‐present element of our existence, point of reference, a deeply beautiful and awesome thing. But it could also, of course, be a threat and force of destruction, particularly in the spring, in flood time.

“After the first crest (in 1973) in late April, there were no bridges open across the Mississippi in the 200 miles between Keokuk and St. Louis, and all the ferries were shut down because their landings were submerged. River traffic was stopped, not only because most of the locks were under water, but because the wash from the powerful engines would endanger the weakening levees even more.

“Quincy, a few miles downstream, was disaster area. Quincy, like Keokuk, is built on a bluff overlooking the river, so most of the flooding was in the low industrial areas, in the farming and fishing‐camp bottomlands, and, particularly, in West Quincy, Mo., directly opposite on the other side of Quincy Memorial Bridge.”

In Hannibal, Kentfield noted the statue of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn “that commands the main street stood shin‐deep in water, as if the boys were going wading in the river, and the calamity there was augmented by a fire that destroyed a printing plant that, though surrounded by six feet of water, could not be saved.”

Surprisingly, casualties were few up and down the river during the flood. Unlike earthquakes or tornadoes, floods like the one in 1973 do not come by surprise.

“Everybody knew it was coming, and they knew from daily measurements of its progress reported in all the newspapers and on the electronic media that they could expect a record high water — but no one had a notion of the phenomenal magnitude of that high,” Kentfield wrote.

Haerr remembers that magnitude.

“I think the (Memorial) Bridge was closed 83 days,” Haerr said.

Hofmeister said it was Christmas until he and his family got back in their house following all sorts of repair work that had been needed.

As bad as the 1973 flood was, both Haerr and Hofmeister felt the 1993 flood was worse.

“We didn’t go back (to where their home had been) after 1993,” Hofmeister said.

The 1973 flood was in large part the result of rainfall during the first half of the year in upper regions of the Mississippi River that exceeded the normal levels by more than 200 percent.

In the 2000 book, “Taming the Upper Mississippi: My Turn at Watch 1935-1999,” the late William Klingner of Quincy noted Hannibal was the hardest-hit city in the region by the flood, with total damage estimated at $4.2 million. Losses in Quincy were estimated at $3.4 million, with the majority of damage sustained by industries along the riverfront. The book, written by Janice Petterchak, serves as both a river history and an autobiography of Klingner, a longtime civil engineer.

The book details that in Northeast Missouri, 3,000 linear feet of sandbags placed on the levee crown were not sufficient to prevent overtopping across the Fabius River Drainage District. The record-high water level of 28.9 feet broke the 1965 mark of 24.8. (That 1973 record fell 20 years later when the river level reached 32.19 feet in the flood of 1993.)

The duration of the flooding in 1973 surpassed that of any previously known records, most notably from floods in 1944, 1947, 1951 and 1965. President Richard Nixon declared disaster areas in portions of Missouri, Iowa and Illinois.

Fifty years later, the flood of 1973 remains ingrained in the memories of men like Haerr.

“I had never seen anything like it before,” Haerr said.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.