Exploring the spirit of Poland: One Quincyan’s journey to Eastern Europe

After Soviet Communists seized control of Poland following World War II, an underground joke circulated among Polish citizens: “Under capitalism man exploits man; under communism, the reverse is true.”

Poland liberated itself in 1989 from the shackles of 44 years of Communist rule and emerged into a fledgling democracy and free-market economy. This joke has not returned.

An extensive trip to Poland led to the discovery among its people a passion for their past and hope for their future found in few countries. This perhaps arises from a history filled to this day with cultural achievements despite nearly eight centuries of feudalism and oppressive monarchical rule and, during the 20th century, tumultuous decades of despotism, depravity and degradation.

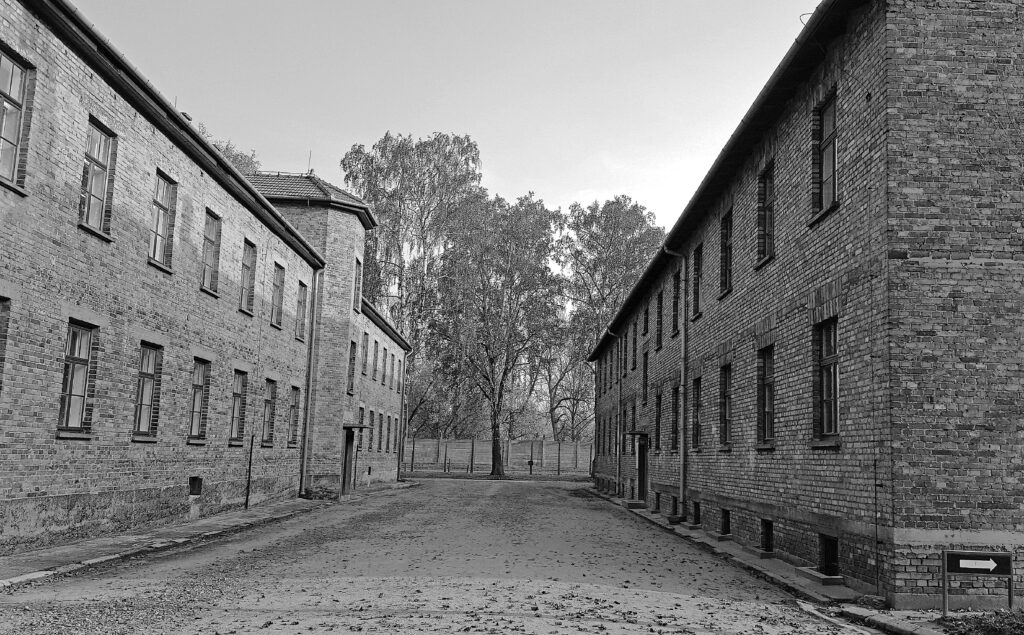

The 1939 German Third Reich’s invasion, occupation and plan to destroy Poland preceded Communist control. Nazis killed nearly six million Poles during World War II either in concentration camps or from bombing, including the annihilation of 90 percent of the Jewish population. Most remaining Jews left the country after the war during Eastern Europe’s mass migration.

The Auschwitz-Berkanau Concentration and Extermination Camp, where Nazis tortured, forced into labor and murdered 1.1 million men, women and children reveals this horrific chapter in Polish history. Auschwitz greeted captives with its ironic entrance sign “Arbeit Macht Frei” (“Work Sets You Free”) while guards later led them to “showers” for asphyxiation with Zyklon B gas. Although Jews comprised nine out of 10 people killed there, the Third Reich’s genocide at this and other camps also included Jehovah Witnesses, the disabled, homosexuals, gypsies and Soviet prisoners.

After the war ended in 1945, the Cold War began and the Soviet Union, now a Communist state, dictated Polish society. These proud people, though, never surrendered their yearning for freedom from outside domination. The most visible and symbolic building from the Communist regime is the 775-foot Palace of Culture and Science built in the capital city of Warsaw to honor Communism and Soviet ruler Joseph Stalin. A painful reminder of repression, this landmark is now a center of capitalist business ventures, finance and commerce. Poles disparagingly call it “Stalin’s Syringe” and “Russian Wedding Cake.” Citizens have defaced the building’s exterior with anti-Soviet and pro-democratic graffiti, but the city makes no effort to remove it.

While Communist authorities tried to suppress religion, a grassroots movement began in the 1950s to openly practice Roman Catholicism. This uprising against political tyranny inspired hope amid widespread despondency. Cardinals then elected Karol Wojtyla in 1978 as the first Polish pope. After taking the name John Paul II (later the Church canonized him as a saint), his calls for a “peaceful revolution” and his ecclesiastical motto “Do not be afraid” kindled religious and ethnic fervor in his native country.

This foreshadowed the freedom Poland gained 11 years later when Communism toppled and the country became an emerging democracy. Today Poland is about 90 percent Catholic, and these ties run deeper than the posturing found in largely Catholic European nations like Italy and France, where members rarely attend Mass or follow church decrees.

Labor activist Lech Walesa also credits Pope John Paul II as igniting the union movement in Poland. Walesa fought for the right of workers to organize and strike. His efforts resulted in a federation of unions known as “Solidarity,” and after 10 million Polish workers and farmers joined the movement, they elected Walesa as chairman. The government outlawed Solidarity in 1981 and arrested and detained Walesa for nearly a year. During the next decade as worker unrest and protests continued, Communist power gradually eroded. In the country’s first free elections in 1991, people chose Walesa as president over the state-appointed candidate, and he presided as Poland evolved into a democracy and free-enterprise capitalism.

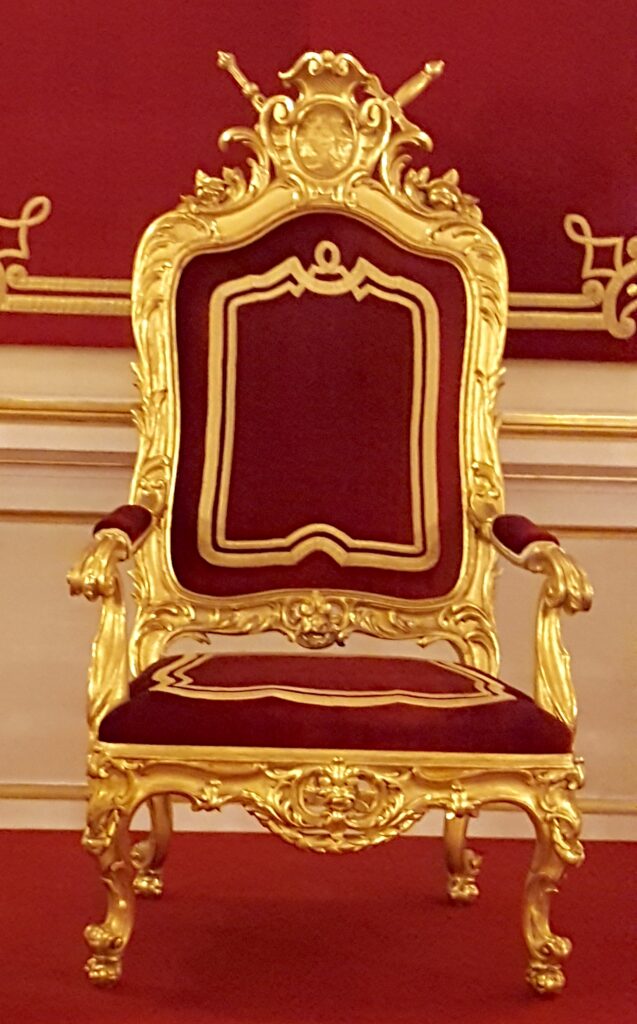

This passion for freedom, such an inherent part of the country’s national character, expressed itself much earlier in its history after Poland established the world’s second constitutional government in 1791— two years after the United States Constitution. But unlike in our own country, Poland only created a titular constitutional monarchy with the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland allied with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Seventy years would pass before the total liberation of peasants from the feudal system that began in the 11th century, with serfs in servitude to local lords. After this perfunctory signing of a constitution, Poles kept clamoring for change.

Perhaps the most profound expression of this yearning for autonomy came from Poland’s greatest composer. Born near Warsaw in 1810, Frederic Chopin transformed the piano into a musical instrument of astonishing virtuosity and grandeur. Many of his compositions reflect his deep love of Poland and wariness of monarchies. While music more than words expressed his political views, Polish historian Zdzislow Jachimecki states that through his work Chopin — more than other progressive Pole of his era — “turned into an original national bard who intuited the past, present and future of his native Poland.”

The Wieliczka Salt Mine in metropolitan Krakow also reveals the indomitable Polish spirit that endured during nearly eight centuries of submission to monarchical rule and later World War II and widespread government oppression. From the 13th to the late 20th centuries, miners — in a labor of love and religious devotion — quarried salt ores which artists later carved into scores of sacred sculptures and four ornate chapels. Wieliczka Salt Mine is now a World Heritage Site and continues to inspire more than one million annual visitors with beautifully crafted work that evokes a cathedral’s reverence and sanctity.

Set against the Tatra Mountains near the southern border with Slovakia, the resort town of Zakopane delights foreign tourists and Poles who travel there for vacations and weekend trips. Traditional culture is celebrated with dress, dance, crafts, foods and games amid a festive atmosphere evoking the country’s steadfast soul, one that embraces the saying from national folklore: “The fear of want is worse than want itself.”

This paradoxical celebration in the wake of so much national sorrow is also seen in Zakopane’s cemeteries, jubilant places of memory and meaning where the faithful embrace age-old religious beliefs. Poles embellish burial sites with garish decorations and mementos of the deceased to hasten the journey to a heavenly afterlife. People make genial pilgrimages to these cemeteries to honor the gift of life and to respect death—at least when death comes in due time and is not caused by human evil.

Poland today is a vibrant society with freedoms of self-government, enterprise and speech. Despite popular misconceptions, the nation’s literacy rate is 99 percent. Its high school students outperform their American counterparts in mathematics and science, and it is the homeland of 18 Nobel Prize laureates.

Poland also has an illustrious scientific heritage. Poland’s most renowned scientist, Nicolaus Copernicus, revolutionized our understanding of the natural world in the 16th century by proposing that Earth is not the center of the solar system but rather, like the other planets, revolves around the Sun. His planetary model, later verified by astronomers, toppled 1,400 years of a geocentric belief. Martin Luther and many theologians rejected Copernicus’ notion as contradicting the Bible and the Catholic Church only lifted its formal prohibition against his theory 400 years after he proposed it.

Poland exudes the optimism of a country only one generation liberated from totalitarian rule and has forged a unique form of free-enterprise capitalism that places the well-being of its citizens above the bottom line. In an astute observation of Polish culture, journalist Michael Kaufman stated in a C-SPAN interview, “Polish life is largely bound with other citizens — in bistros, town halls, with friends over glasses of vodka. The likes of the rugged American individual is not found there.”

Throughout their tempestuous and tragic history, Poles have held onto values that define themselves and the kind of society and lives they want to create. The state serves the people, the spirit is more vital than the physical and sharing is more ennobling than self-seeking.

This national spirit is shown in its continuing effort to physically rebuild after WWII destroyed 80 percent of Warsaw’s buildings and devastated most of the rest of Poland. Citizens here embrace their ethnic identity, and a large majority believe immigration to their country should be banned. They remain unfazed that this stance does not fare well with the European Union or most Western nations.

Poland realizes it stands at the crossroads of history. In remembering and reflecting on its past, this country strives to continually rise from literal ashes and regain eminence in the world.

The Polish saying, “If it is humanly possible, it is within your reach,” came to mind often while traveling throughout this land whose soul melds faith and a striving for freedom into the will to overcome the most daunting obstacles.

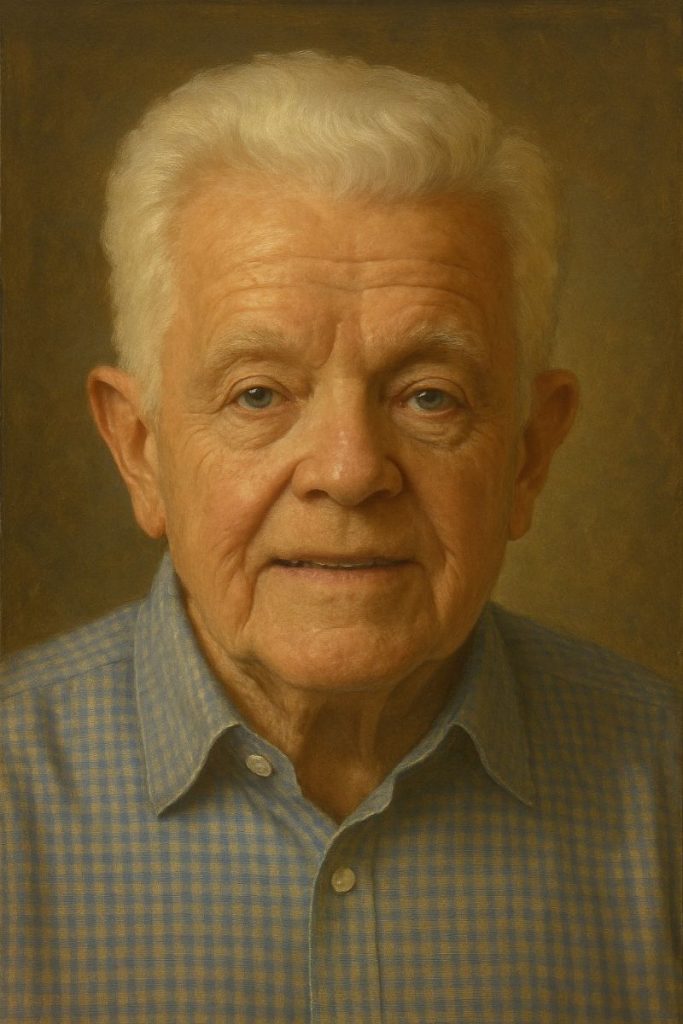

Joseph Newkirk is a local writer, photographer and world traveler who has published many of his adventures in newspapers and literary magazines. He is a board member of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, Quincy Museum, Friends of the Log Cabins and the Quincy University Retired Faculty and Staff Association.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.