Down on the Delta: A Quincyan explores the soul of New Orleans

The Mississippi River begins in northern Minnesota’s Lake Itasca and flows for 2,340 miles through 10 states before reaching its basin in southern Louisiana’s port of New Orleans. The river runs by Quincy and has influenced the city’s history and culture since its founding. Likewise, during the nearly 300 years since French colonists arrived on land originally occupied by Native American Chitimacha, the Mississippi River has entwined itself with New Orleans’ color, exuberance and mystique.

Named after the Duke of Orleans and nicknamed “The Big Easy” and “Crescent City,” this bayou settlement where the Mississippi opens into the Gulf of Mexico reveals some intriguing features of American life: Mardi Gras, slave trading, voodoo and jazz. Each of these facets of Americana has also played a role in other river towns like Quincy.

As perhaps more than in any other place in the United States, New Orleans celebrates life and strives to rise above hardships and tragedies with festivals, parades and an omnipresent music that gives rhythm to delta days and nights.

Mardi Gras (which means “Fat Tuesday” in French and is a legal holiday in Louisiana) hosts the best-known local parades. Although now widely seen as a last fling of exuberance before the austerities of Lent — complete with more than one million revelers cavorting the streets with intoxicants, lust and reckless abandon — Mardi Gras originated in a Catholic holy day called “Shrove Tuesday.” On this day, the faithful examine their lives, make confessions and commit themselves to be kinder to people and better stewards of creation. Like much in modern life, religious origins have been obscured and displaced by popular secular renderings.

Private clubs known as “krewes” first constructed floats for Mardi Gras parades to showcase their prominence in New Orleans society and enhance their mystique by displaying enigmatic figures whose meanings were known only to members. Now large companies mostly construct floats in a year-round business producing creations that bedevil the imagination and dazzle the crowds. The Rex Parade is the largest and most extravagant on Mardi Gras, and a distinguished New Orleans citizen is annually crowned the Rex King. As floats pass by, they toss out hundreds of thousands of beaded necklaces, which usually end up lodged on trees. The city makes no effort to remove these necklaces but sees them rather as an icon of this place where the party never ends.

In 1909, New Orleans’ African-American community began spoofing the Rex Parade with its own “Zulu Parade.” Over the years, it has become a way to recognize and laud the contributions of black citizens to Louisiana culture. The Zulu Parade named the renowned jazz musician Louis Armstrong as Zulu King in 1939 when the city banned him and other black people from white restaurants, hotels and Krewes.

New Orleans did not desegregate its public schools until 1960 (six years after the United States Supreme Court decision in Brown v. the Board of Education) and fiercely enforced Jim Crow laws. For several decades, as with many river towns like Quincy, New Orleans had legalized prostitution, and even these — at least in Crescent City —remained segregated. Black brothels operated only in the Storyville District, although white patrons often frequented them.

Many of the immigrants who settled in Quincy during the late 19th and early 20th centuries came through the port of New Orleans. Cruises for tourists on paddleboats like the Natchez and Creole Queen model themselves after 19th-century voyages on vessels that docked in Quincy, Hannibal and Keokuk when the Mississippi River hailed as the country’s primary means of transport and trade.

These cruises reenact the time depicted in Mark Twain’s book “Life on the Mississippi” when rivers symbolized life’s possibilities, for immigrants, adventurers, and those desiring a fresh start in life. Complete with a Dixieland band, a poker room and Cajun and Creole buffets, paddleboats provide panoramic views of New Orleans and present the genteel side of river culture. However, they gloss over the ghastly reality of slavery.

This heinous injustice scarred our country’s antebellum life and found a major slave-trading market in Crescent City. Owners forced slaves not only to cultivate crops and serve them as domestic help but to build their shanties by hand in back of plantations. Ironically, slaves also largely crafted the meticulously detailed iron grill work gracing the balconies in New Orleans’ Vieux Carre or French Quarter. During an era when “race superiority” dominated thinking, most people never acknowledged the skill and workmanship of slaves.

The Destrehan Plantation outside of New Orleans is the oldest documented plantation in the Mississippi Valley. For nearly 80 years, captured Africans and Caribbeans labored in sugar cane and indigo fields. The plantation’s tour guide notes that slavery also included indigent European immigrants and in Louisiana “Free Men of Color” owned both black and immigrant slaves. The guide also adds, with a grimace, that many people quoted the Bible as endorsing slavery with passages such as Ephesians 6:5-8 and Colossians 4:1.

Destrehan Plantation is among the sites involved in the largest slave uprising in American history: The 1811 revolt when for three days in January about 500 slaves, armed mostly with hand tools, tried to seize control of New Orleans and establish their own government. In the aftermath of this revolt’s suppression, the Louisiana State Militia found that a few owners and 66 slaves had been killed during the fighting. Later the Militia captured 18 slaves, executed them and placed their heads on pikes for public viewing. Slavery would continue for another 54 years.

Today African Americans comprise about 60 percent of the city’s population. Slave collars, whipping posts and human auction blocks are museum artifacts. How deeply the institution of slavery still affects American society remains debatable. People of nearly every ethnic heritage and nationality call this city home, and like the flamboyant attire and extravagant demeanor found here, physical and cultural variations complement the local scene.

New Orleans is like a mix of gumbo: a little of everything adds to the flavor. Long before “diversity” entered our national dialogue, New Orleans had its own version.

Slaves gave rhythm to grueling labor and eased their pains by singing as they picked cotton and harvested crops. First accompanied by homemade instruments, these work songs, or “field hollers,” emerged into the “blues” and later mingled with ragtime and African cadences before evolving in New Orleans and elsewhere into America’s original music: jazz.

The French Quarter’s “New Orleans Jazz Historic Park” showcases the early sounds of Buddy Bolden and Jelly Roll Morton to later musicians like Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald. In improvising and savoring the here and now, jazz embodies the energy and élan of marginalized people with clouded pasts and uncertain futures. This music has the potential to transform suffering into momentary sound. Jazz funerals begin somberly and then end in celebration as death severs earthly bonds and frees the spirit, just as many slaves saw death as liberation from this world’s misery.

As in many large American cities, street performers add to the local color. New Orleans, though, is unique in its large number of “living statues” or mimes who remain immobile (sometimes for several hours) until a passerby offers money to “unfreeze” them. These costumed characters who appear carved in stone carry on an ancient art form (yes, schools exist that teach this technique to prospective performers) that blends theater, choreography and physical discipline.

Elizabethan plays, including several of Shakespeare’s, featured living sculptures and were popular in Medieval and Renaissance pageantry and many European operas. New Orleans, with its French and Spanish influences, became the first opera capital of the United States. In the late 19th century, it had the second-largest opera house in the country.

Many other cultures besides French and Spanish contributed to the atmosphere of this major port city. Nowhere is this diversity more delightfully expressed than in the city’s cuisine. A culinary fusion first evolved from the cooking of Creoles (descendants of the first settlers here: French, Spanish, Native American and Africans) and Cajuns or Nova Scotians who migrated here from Canada rather than abandon their Catholic faith during the country’s British rule. Later this cuisine added Italian, Caribbean and Eastern European overtones, as people passed through and sometimes settled here.

This culinary artistry layered itself upon traditional Southern cooking, where people lived close to the land and made meals from the food they grew. Southerners have historically created recipes that show their respect for the Earth and the arduous toil needed to harvest its bounty. Only recently have fast-food restaurants sprung up across New Orleans, and many local gourmands bemoan their presence in a locale known for fine food and dining.

Largely because of its French and Spanish heritage, New Orleans — and much of southern Louisiana — is predominantly Roman Catholic. Indeed, Louisiana today is the only state south of the Mason-Dixon Line with a majority of this denomination. When slaves from Africa and the Caribbean brought their indigenous beliefs to this country and mixed with a corrupted form of Catholicism, a new spiritual path arose in a tradition still widely practiced here: voodoo.

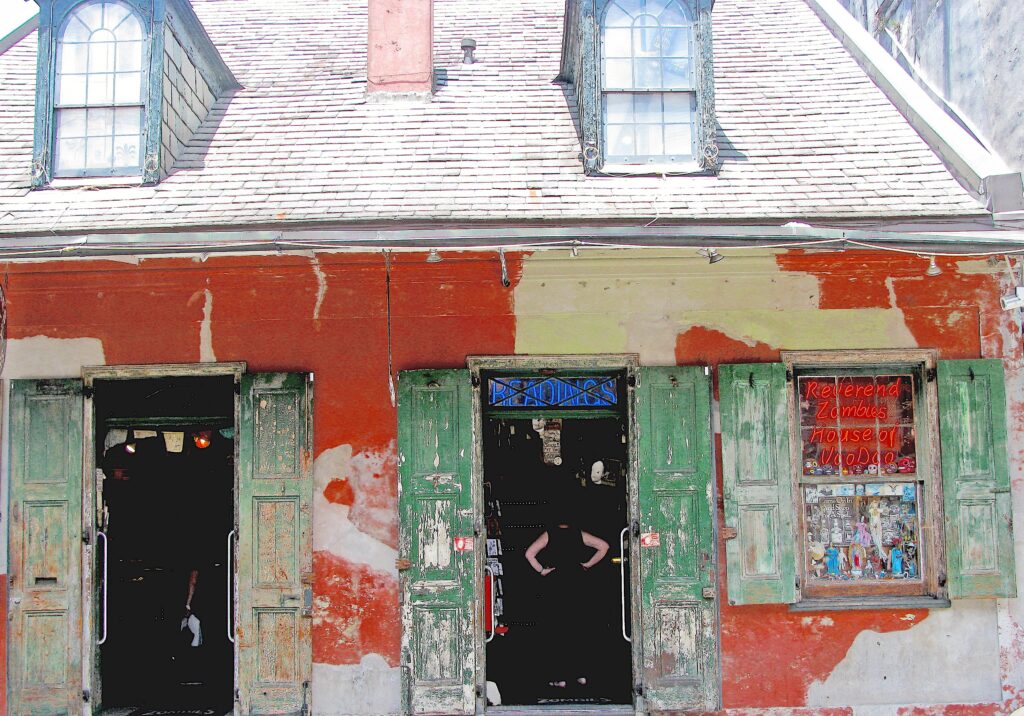

The St. Louis Cathedral, completed in 1794 and North America’s oldest Catholic cathedral, and Dumaine Street’s Historic Voodoo Museum showcase Crescent City’s unique melding of religious orthodoxy and ancient animism. Although most of the “voodoo” found in New Orleans panders to tourists, calling it “superstition” or “folklore” is simplistic. Voodoo’s underlying philosophy largely dovetails with modern science: humanity and nature need to sustain harmony; Earth generates forces that profoundly shape history. Life and death remain necessary ends of the same pole.

While they differ in significant ways, Catholicism and voodoo have shared beliefs in monotheism, an afterlife and the ultimate grace and goodness of creation. Many voodoo practitioners consider themselves Catholics and attend Mass along with their ceremonies and rituals. Like much derived from popular Hollywood images, though, only the most flagrant and bizarre aspects abound in national consciousness.

Necessity, though, and not spiritual beliefs prompts New Orleans to bury most of its dead in above-ground graves and family vaults. The city is between one and seven feet below sea level and underground excavations would unleash a torrent of water literally washing coffins out of the ground. This factor combined with a lack of space to bury the dead forced cemeteries to build tiered grave sites with coffins stacked atop one another. A docent at the St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 reminds visitors that the heat and humidity bellowed into these enclosures swiftly decompose bodies. Caretakers then use a “shaft” to recycle the space for another family member by sweeping remains into a common bin at the back of the vault. This originated the expression “get shafted.”

As the docent wryly grins, one realizes a gallows humor is needed here to get through life without stultifying solemnity.

After the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, though, many New Orleans citizens felt shafted by FEMA’s (Federal Emergency Management Agency) slow response, ensuing bureaucratic malaise, and greed’s pervasive maligning. Although the hurricane itself did great damage, flooding is now acknowledged as the major cause of destruction.

This flooding largely resulted from government officials and private industry leaders ignoring for many years ecologists’ warnings about encroaching erosion to natural barriers of wetlands and marshes along the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico. The main culprits were gas and petroleum refineries that looked more at their bottom lines than their environmental impact.

In other words, the consensus of most scientists is that the bulk of Katrina’s ravages — more than 1,800 people killed, 800,000 left homeless and $186 billion of damages (2022 USD) — were man-made and preventable. The aftermath of Katrina has indelibly marked the city. The poverty rate in New Orleans today is about 23 percent, twice the national average. With about 1,500 homeless people living in shelters or on the streets and the highest murder rate in the country, the misery index has dramatically increased since the storm. About one in four New Orleans citizens left the city for good, and homeowners and businesses were stranded with over $100 billion in uninsured losses (2022 USD). Thousands of jobs were lost and never replaced.

While the recovery effort faced many obstacles and much work still lies ahead 19 years later, the city steadfastly moves beyond adversity. The population has rebounded, and tourism and revenue are increasing. The return of the New Orleans Pelicans professional basketball team, which relocated in Oklahoma City after Katrina, and the reopening of the iconic Louisiana Superdome (now Caesars Superdome) that housed 20,000 people during the hurricane and its aftermath buoyed the city’s spirits. While parts of the Lower Ninth Ward and other neighborhoods remain boarded up and remind people of the disaster that forever changed their lives, New Orleans has a refurbished downtown and waterfront. Scores of businesses have opened, and several major corporations moved here.

Throughout its turbulent history, “The Big Easy” has expressed its tenacious and resilient soul — from the unabashed frolic on Bourbon Street, to the bayou’s down-home shindigs, to tourists biting into a beignet. Across the city, the sounds of jazz, blues, zydeco and other musical genres inspire a joie de vivre through life’s troughs and crests, misery and majesty, poignancy and promise.

As the renowned New Orleans jazz musician Joe “King” Oliver told his audiences: “The past and the future, heaven and hell, are with us now. So let’s keep making music and dancing!”

In Louisiana, a “lagniappe” is a small gift merchants give customers extending goodwill and friendship. New Orleans, that flamboyant Delta city at the mouth of the Mississippi River, continues to offer life its special lagniappes.

Joseph Newkirk is a local writer, photographer and world traveler who has published many of his adventures in newspapers and literary magazines. He is a board member of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, Quincy Museum, Friends of the Log Cabins and the Quincy University Retired Faculty and Staff Association. He went to New Orleans in May and explored a colorful, mysterious and romantic place that many people have popular, if skewed, notions about. Every reader knows about the “Muddy River,” and Newkirk hopes a story about the river’s first settlement may well kindle a greater appreciation for their present locales and how New Orleans has influenced every city and town along the river’s path.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.