Measles Unmuddied: What to know about the virus, the current outbreak and the MMR vaccine

QUINCY — Despite having been declared to be eradicated in this country 25 years ago, one of the most contagious viruses in the world is on the rise in the United States — and cases are getting closer and closer in proximity to the Quincy and Hannibal, Mo. areas.

A cluster of measles cases was confirmed in January within a mostly unvaccinated Mennonite community in West Texas. By February, cases had well surpassed 100, 18 people had been hospitalized and the first death — an unvaccinated school-aged child with no underlying conditions — had been recorded with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Additionally, the outbreak had spread to New Mexico.

It spread to several other states in March, and another death — a second unvaccinated school-aged child with no underlying conditions — was recorded in Texas in early April. (Another potential measles-related death occurred in New Mexico in March in an unvaccinated adult, whose body tested positive for the virus. The cause of death is still being investigated.)

The first cases were reported in Illinois and Missouri in April. Current counts are up to eight and two, respectively.

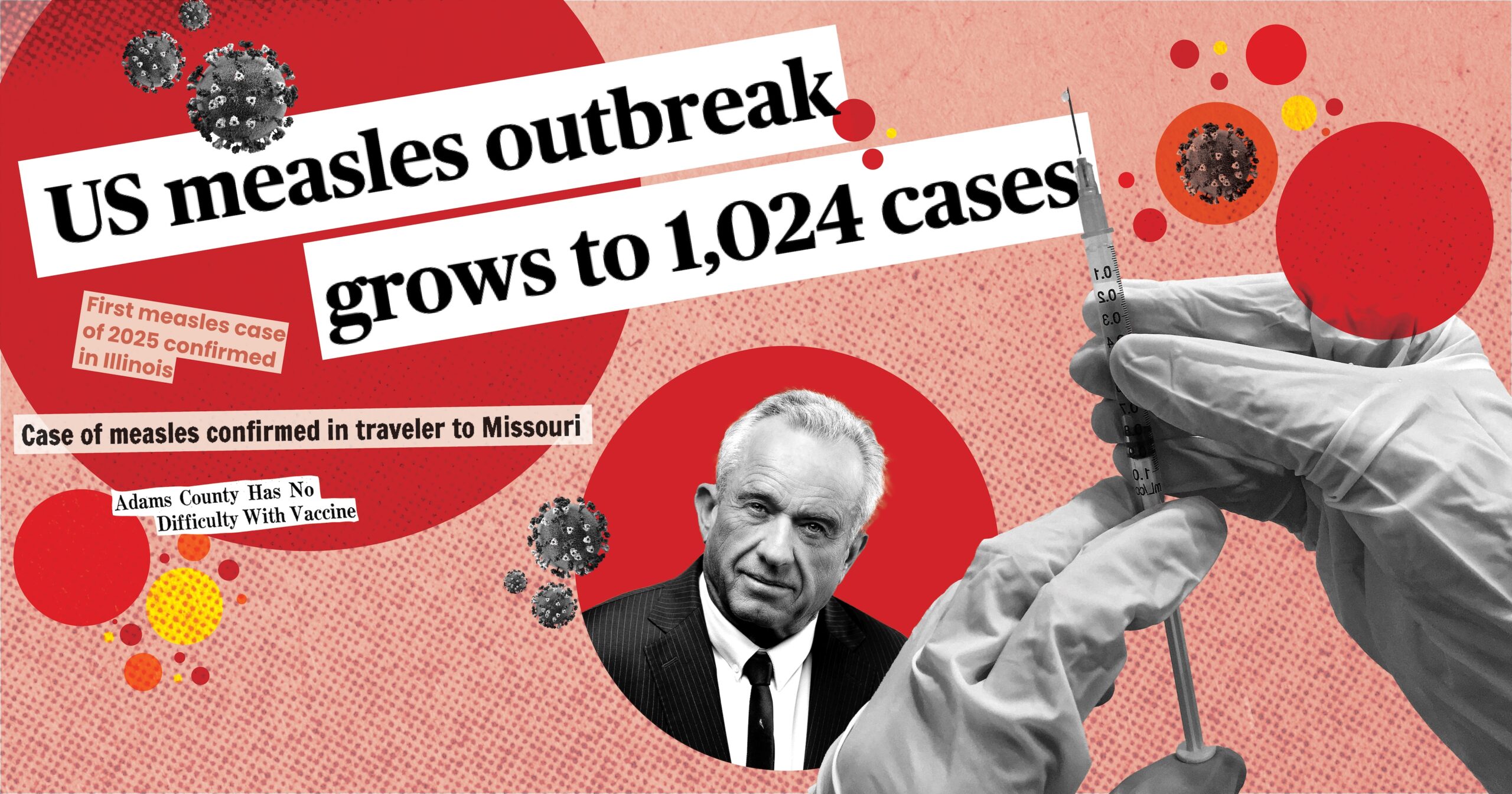

As of mid-May, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has reported 1,024 total cases — more than triple the amount of cases recorded in all of 2024. Nearly all cases (96 percent) have been identified in unvaccinated patients. Nearly 70 percent of cases are in patients age 19 and younger, and patients under age 5 account for more than half of all hospitalizations.

What is measles? Is it really that big of a deal? What’s with the vaccine? Is it safe? What are the chances an outbreak could occur here? Are medical facilities prepared for another viral outbreak?

To find out, Muddy River News consulted with:

- Dr. Adnan Mushtaq, an infectious disease physician at Blessing Health System

- Tonya Stamper, a family nurse practitioner with a doctorate of nursing practice at Clarity Health Care

- Dr. Hala Saad, an infectious disease physician at Quincy Medical Group

Is measles really that big of a deal?

A few characteristics of measles make it a particularly stubborn virus. The first is its contagion rate.

The World Health Organization considers measles to be one of the most contagious viruses in the world. Like many other viruses, measles is spread through particles in the air and can remain airborne for up to two hours. Exposure to measles will infect roughly nine in 10 susceptible people, according to the CDC.

A person doesn’t have to inhale an abundance of infectious particles to get sick. An outbreak among athletes at the 1991 Special Olympics resulted in the infection of two spectators unrelated to each other who’d both been sitting in the same section of the arena nearly 100 feet away from where infected athletes were.

Experts estimate that if someone infected with COVID-19 were to walk around in a populated area, one to three people would become infected. The flu which would infect one to two people, polio would infect five to seven and chickenpox would infect about nine. The number for measles averages about 12 to 18 in completely susceptible populations.

According to the Illinois Department of Public Health, the first symptoms typically arrive between the seventh and 18th day after exposure but can take up to three weeks to appear. Initial symptoms include a high fever, runny nose, cough and red, watery eyes.

Roughly 14 days after exposure comes the maculopapular rash — a rash with both flat and raised lesions on the skin that often accompanies an infection or allergic reaction. It typically starts on the face, hairline and behind the ears and neck before making its way to the rest of the body. It lasts at least three days, but an infected person is contagious from four days before the rash appears to four days after the rash has subsided.

The National Foundation for Infectious Diseases states that roughly one in five cases will require hospitalization and that one to three out of every 1,000 cases will be fatal, meaning that the majority of people who contract measles will survive without needing to be hospitalized.

However, while the symptoms alone might lead some to believe that measles is just another mild illness, it’s a bit more complicated.

A 2018 academic review of various studies on measles in the Hong Kong Medical Journal said complications will arise in 10 to 40 percent of cases and are unsurprisingly more common in people who are immunocompromised, elderly or pregnant, along with infants. A few such complications are:

- respiratory complications, like pneumonia, tonsilitis and bronchitis;

- gastrointestinal complications, like hepatitis, pancreatitis and appendicitis;

- ophthalmological complications, such as blindness;

- and neurological complications, like febrile seizures and encephalitis.

The article noted that another neurological complication, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), typically doesn’t present itself until five to 10 years after the infection. The condition is extremely rare but almost always fatal.

A case study published in 2021 outlined the story of a 16-year-old boy who initially sought medical assistance for “worsening generalized weakness and urinary incontinence.” His condition progressed to include severe headaches, periodic losses of consciousness, seizures and other symptoms. Comprehensive blood testing led to the diagnosis of SSPE, which occurred as a result of a measles infection he had at 2 months old — more than 15 years prior. Within months of the onset of his symptoms of SSPE, the boy was dead.

Spontaneous abortion, premature labor, low birth weight, stillbirth and maternal death are all at an increased risk for people who contract measles while pregnant.

Additionally, several studies have found the virus to cause “immune amnesia” for up to five years after infection. Notably, this “amnesia” doesn’t just occur in severe cases and is increasingly described as a general characteristic of the virus with common occurrences.

“Measles virus is especially dangerous because it has the ability to destroy what’s been earned: immune memory from previous infections,” noted an article published by the American Society for Microbiology. “If (measles virus) infection essentially resets a child’s developing immunity to that of a newborn, re-vaccination or exposure to all previously encountered microbes will be required in order to rebuild proper immune function.”

The virus’s detrimental effects on the immune system further complicate other diseases that would have been much more manageable if not for the initial measles infection, leading to death in some instances.

How bad would an outbreak be in our area?

Throughout nearly three decades of working in healthcare, Stamper has never encountered a case of measles.

Saad and Mushtaq have, but not in the United States. Mushtaq observed cases while interning in Pakistan, where the virus remains prevalent, at the beginning of his career. Saad encountered some while in medical school in Lebanon.

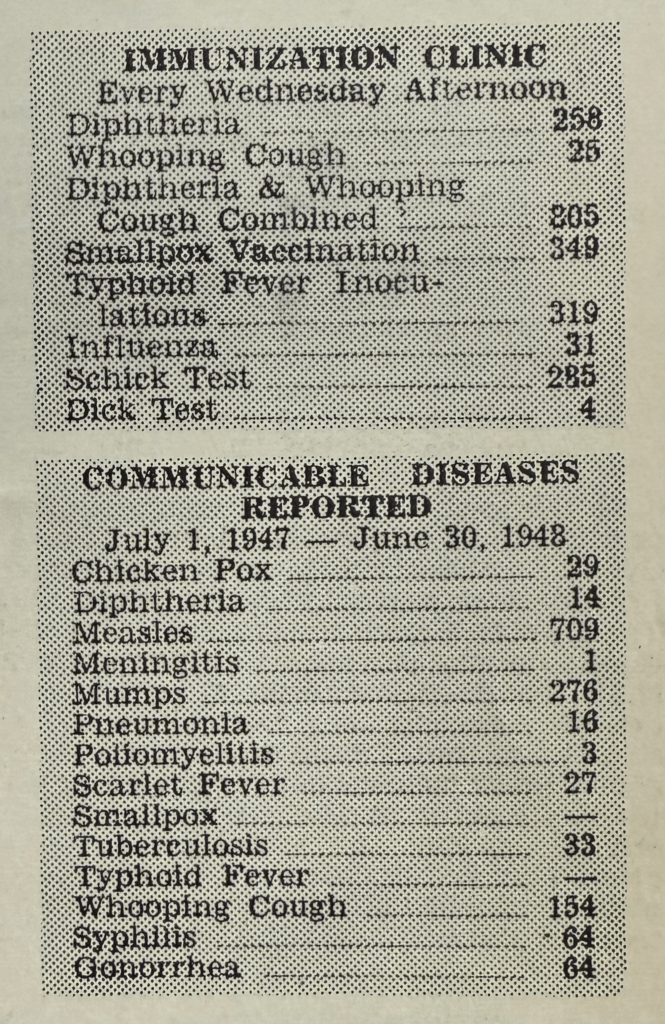

Adams County hasn’t reported a single case of measles since the early 90s, when two unrelated cases were reported between 1991 and 1993. A small outbreak of 10 cases occurred in 1986, and an outbreak of 113 cases was reported 10 years prior in 1976. The virus wasn’t present in the county at all in the time between the two outbreaks.

In a community that hasn’t encountered a single instance of the measles virus in more than 30 years, how prepared are its healthcare facilities to handle an outbreak if one comes?

“Our infectious disease and infection prevention department at Blessing Health System is fully equipped to deal with these cases,” Mushtaq said.

Saad and Stamper also assured that Quincy Medical Group and Clarity Healthcare have plans, procedures and protocols in place to address viral diseases like measles. However, as healthcare facilities across the country observed throughout the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, facilities can quickly become overwhelmed and low on resources — regardless of the level of preparation beforehand.

“We have seen the impact that recent RSV (respiratory syncytial virus), COVID and influenza outbreaks have had on our healthcare facilities. Emergency rooms have had to divert patients, hospitals have had no beds and clinics can’t see enough patients in a day to address the need,” Stamper said.

The National Foundation for Infectious Diseases says one in five people who contract measles will require hospitalization.

“This could certainly place a huge burden on our hospital system as well as outpatient clinics, where most of those affected will initially present for treatment,” Stamper said.

As far as the national response goes, experts at Boston University said there are reasons to be optimistic. Among them are:

- Incredible developments have been made with vaccines;

- The country learned a lot during the coronavirus pandemic;

- The international community learned to work together quickly; and

- Artificial intelligence could be used to assist various response measures.

They also noted reasons to be concerned.

- Relationships between the U.S. and many nations have become hostile in recent months, which could jeopardize international unity in fighting another worldwide pandemic;

- Many vaccine programs facilitated by the U.S. in developing countries have been slashed;

- Vaccine hesitancy is increasing; and

- Disparities in healthcare.

“Preparedness depends on staffing, resources and community vaccination rates,” Saad said. “A surge in cases could strain facilities, making prevention crucial.”

All providers agreed on the best way to prevent a measles infection: vaccination.

Anyone born before 1957 is likely immune to measles due to previous exposure. Most adults have received two doses of the MMR vaccine, but county health records and blood tests can confirm for people uncertain of their vaccination status.

MMR vaccine safe and effective

The measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine was released in the early 1970s. In less than three decades, the virus that was once responsible for three to four million infections, up to 500 deaths, nearly 50,000 hospitalizations and 1,000 cases of encephalitis each year in the U.S. became one of only seven diseases to be considered eradicated in the country — all thanks to the MMR vaccine, which is 97% effective at preventing infection with the recommended two doses.

Before the administration of the first vaccines in the late 1700s, nearly half (46 percent) of all children born in the U.S. died before their fifth birthday. Several lifestyle improvements, such as sanitation and nutrition, and significant medical advancements like vaccination caused the percentage to plummet to about three percent by 1970 — just before the MMR vaccine was released.

The rate is now less than one percent (0.65%) in the U.S., but it is higher in the places Saad and Mushtaq had observed measles cases firsthand. UNICEF says Lebanon’s childhood mortality rate is around two percent, while Pakistan’s is nearly six percent.

The successful eradication of the disease is increasingly threatened by vaccine hesitancy, which is further exacerbated by skeptics like Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the recently appointed secretary of health and human services. He claims the MMR vaccine is ineffective and unsafe, contains aborted “fetal debris” and causes autism.

“We’re always going to have measles, no matter what happens, as the vaccine wanes very quickly,” Kennedy said in an interview with CBS last month.

He also claimed that “the vaccines wane about 4.8% per year.” A 20-year study conducted by researchers from the National Public Health Institute found that the vaccine’s efficacy decreases in regard to preventing an infection of mumps, but most people who receive both recommended doses of the MMR vaccine are considered immune against measles and rubella for life.

Additionally, unlike the flu and COVID-19, the measles virus only infects humans. The Journal of Infectious Diseases says measles could be completely eradicated across the globe if everyone got vaccinated until existing cases subsided.

The MMR vaccine comes with side effects. One in 10 children will likely experience a fever after getting the vaccine, and roughly one in 20 will develop a rash that typically resolves in two to three days.

Fever-induced seizures, known as febrile seizures, can occur. According to the CDC, a reaction of that nature is rare, occurring in roughly one out of every 3,000 to 4,000 children. A child is three to 12 times more likely to die of measles than they are of experiencing a febrile seizure after getting the MMR vaccine.

Kennedy claimed the Texas outbreak started in the Mennonite community because they have religious objections to the MMR vaccine — because it “contains a lot of aborted fetus debris and DNA particles.”

Fetal cells from an abortion that occurred in the 1960s were used to develop the first iterations of the rubella portion of the vaccine. While the cells in the vaccine today can certainly be traced back to those origins, the vaccine does not contain “aborted fetus debris and DNA particles.” As Reuters reported earlier this month, the cells are the product of decades of replication “in test tubes in laboratory settings, thousands of times removed from the original ones.”

A full list of the vaccine’s side effects and ingredients is available through the Food and Drug Administration.

The MMR vaccine’s relationship to autism has been a topic of controversy since the late 1990s. English doctor Andrew Wakefield published a study in the Lancet, a highly respected peer-reviewed medical journal, that suggested the vaccine caused autism in otherwise healthy children. The study included 12 children between the ages of 3 and 10 “who, after a period of apparent normality, lost acquired skills, including communication.”

Wakefield’s study was retracted by the Lancet in 2010. He also lost his medical license after an investigation by the General Medical Council (GMC) found him to have “repeatedly breached fundamental principles of research medicine” in the study, including subjecting children to invasive medical procedures and violating research ethics and financial conflicts of interest, as reported by the Guardian in 2010.

The GMC alleged that Wakefield had performed unnecessary colonoscopies and lumbar punctures on the children in the study, and that he had repeatedly injected one child with an experimental drug that had been proposed as an alternative to the MMR vaccine — which he happened to have a financial interest in. The council also found that his research had largely been funded by legal entities that sought to sue vaccine manufacturers — a difficult task without scientific evidence proving a causal relationship between the MMR vaccine and autism.

Additionally, associations between the vaccine and autism were self-reported by parents (not an observation found during independent testing), there was no control group or period and the study did not include findings from all children observed.

The Wakefield study is widely considered by the scientific community as fraudulent and was named in a 2020 study as a propagator of confirmatory bias — “the tendency to seek out information that supports pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses while disregarding contradictory evidence.”

Wakefield’s claims have been disproven in dozens of academic articles and studies over the years, including a 1999 study by researchers from the same medical institution that once employed Wakefield and a 2002 study with a sample of more than 500,000 children. However, the damage has been difficult to reverse, as a 2023 study found that the fear of autism was the most commonly cited reason parents gave for forgoing vaccinating their children against measles. Additionally, a 2024 survey from the Annenberg Public Policy Center found that one in four adults in the U.S. still believe the vaccine causes autism.

(More studies disproving Wakefield’s claims can be found here.)

“Vaccine hesitancy has played a huge role in this resurgence. There is a lot of misinformation about vaccines being spread through social media and other outlets,” Stamper said.

An immunization rate of 95 percent or higher is recommended to prevent measles outbreaks. Four of the six cases in Illinois have been reported in Southern Illinois, where school immunization rates are as low as 77.6 percent in some areas. The other two cases were reported in Cook County, which has school immunization rates in the low 80s. (All six cases have been reported among adult patients.)

Though the average immunization rate in Illinois has slowly but steadily declined in recent years, Adams County has remained mostly unchanged in the last decade. For the 2024-25 school year, every school in the county reported rates between 95.8 and 100 percent.

Neighboring Pike County is a different story, with an average rate falling below both the state average and the required 95 percent to prevent an outbreak. The average rate for the county is around 92 percent, with one school, Pike County Christian Academy, falling under 50 percent.

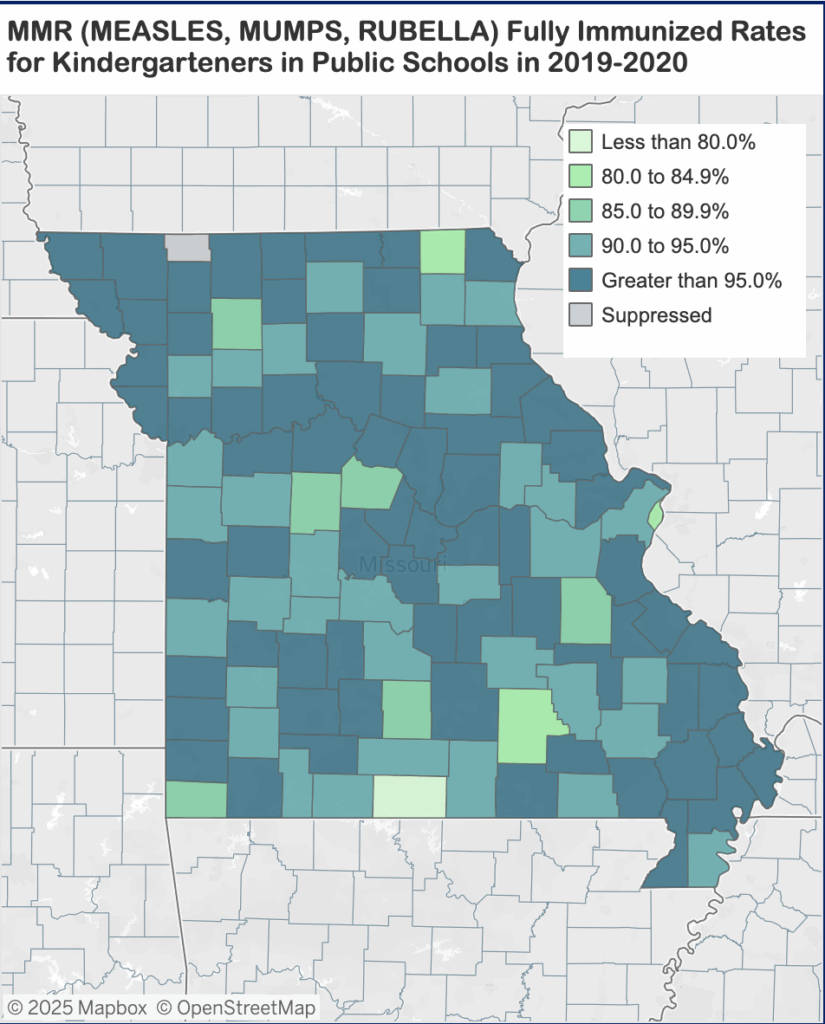

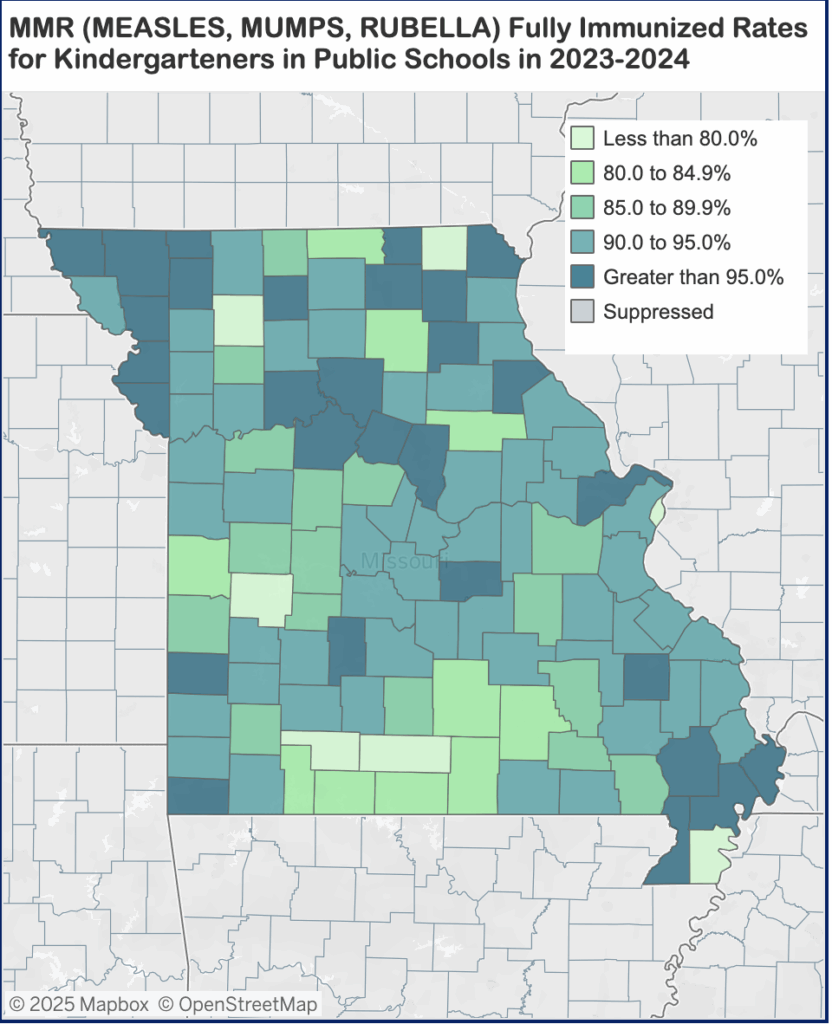

A Missouri child tested positive for measles after returning home from an international trip to Taney County, where the kindergarten immunization rate for the MMR vaccine was around 83 percent during the 2023-24 school year.

A second case, an adult visiting the St. Louis Aquarium from out of state, was confirmed at the end of April. The average kindergarten MMR immunization rate in St. Louis City County was 75 percent during the 2023-2024 school year.

According to the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, Missouri counties in 2019 had a kindergarten immunization rate of 90 percent or higher, and the state average was 97 percent. It was even higher for eighth graders, with nearly the entire state achieving immunization rates of 95 percent or higher and a state average of 99 percent.

Those rates have significantly decreased in the time since, especially among kindergartners. Roughly half of Missouri counties now have kindergarten immunization rates ranging between 61 to 89 percent — far below the 95 percent rate needed to prevent an outbreak.

One of the most dramatic declines in the state has been in Scotland County in the northeastern part of the state. Rates fell more than 20 percentage points for kindergartners in recent years from an already-low rate of 80 percent in 2019 to 58 percent in 2024 — the lowest in the state.

Though more likely to occur in Missouri than Illinois based on current immunization rates, the chances of a severe outbreak occurring in either area remain low at this time. Additionally, while the virus continues to make its way through Texas, the spread to other states appears to be slowing.

Be that as it may, 2025 has garnered one of the most severe measles outbreaks in the U.S. since the early 90s, second only to 2019 when 1,274 cases were reported. Nearly one in five cases since 2000 have been reported this year.

“If you have concerns regarding any vaccine, I recommend talking to a trusted health care provider so that you can discuss the risks and benefits and develop a plan to keep you and your family safe and healthy,” Stamper said.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.