A trip to Twain’s “other” home on his birthday

HARTFORD, CT – Ask most Tri-State residents what comes to mind when they hear the name “Mark Twain.” You’ll probably get recollections from Hannibal’s most famous son’s growing-up years: visions of connived fence-painting, treks in forbidden caves, the endless lure of the Mississippi River, and perhaps even a misplaced (but celebrated) jumping frog.

The more erudite might remind you that Hannibal is where young Samuel Clemens became a journalist. That it’s where the gifted 11-year-old—forced to quit school and go to work after the death of his father—poured himself into learning to typeset and honing his gifts of astute observation and writing during seven years of employment at three Hannibal newspapers. They might even tell you it’s where young Sam published his first work, “A Gallant Fireman,” in 1851.

Trouble is, if your picture of Mark Twain ends with his Hannibal years, you’ll miss the full story—the story of how the provincial child of a slave-owning family evolved to become one of the keenest commentators and critics of slavery and the economic inequities of life in the post-Civil War/industrializing United States.

To round out the picture, a trip to the Mark Twain House and Museum at Hartford, CT is a good bet. It’s here that Clemens claimed he spent the happiest 20 years of his life. It’s here you’ll get a glimpse of why.

A Circuitous Route to Hartford

Today is the 186th anniversary of the great American author’s birth in Florida, Mo. His family moved to Hannibal when he was four and then, at the tender age of 18, Clemens left Hannibal for good in June 1854. He spent the next 14 years figuring out what he really wanted to be when he grew up.

Clemens spent three years working as a journeyman typesetter for newspapers in St. Louis, New York, Philadelphia, Muscatine and Keokuk, Iowa, and Cincinnati; a couple years training as a Mississippi River pilot and a couple more years piloting riverboats between St. Louis and New Orleans, and a brief stint in the Confederate Hannibal Home Guard after the Civil War broke out in 1861, resigning just two weeks later to follow his brother Orion to the Nevada Territory out west.

After an attempt at silver mining, Clemens became a reporter for the Virginia City newspaper in 1862. The following year, he adopted the pen name “Mark Twain.”

For the next several years, he worked for newspapers in California, finding a niche in travel writing and lecture circuit after a successful reporting gig in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) in 1866.

Twain’s first book, “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, and Other Sketches,” debuted in 1867. The same year he arrived in New York, quickly gaining celebrity as a journalist, travel writer who visited Europe and the Holy Land, and lecturer.

During this time, Twain met and courted Olivia Louise Langdon, a cultivated and well-educated woman of substantial means some ten years his junior, in Elmira, N.Y. He and “Livy” married in 1870. After a year in Buffalo, the couple moved to Hartford.

The Allure of Hartford’s Nook Farm

It’s not coincidental that Samuel and Livy settled in the Nook Farm neighborhood on Hartford’s western edge. Nook Farm was purchased by John Hooker and Francis Gillette in 1850. After the Civil War, gifted members of the Hooker and Gillette families and their friends began to move there. Soon, the 140-acre farm became one of the United States’ most notable enclaves for reform-minded writers, politicians, and social activists.

Among Nook Farm’s most famous residents were Harriet Beecher Stowe of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” renown, who settled there in 1864; Isabella Beecher Hooker, Harriet’s half-sister and John Hooker’s wife, one of the nation’s foremost advocates for women’s equality and right to vote; and Charles Dudley Warner, a prominent travel writer and editor with whom Clemens co-authored “The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today,” a commentary on Post-Civil War corruption and consumerism, published in 1873.

For their first couple years at Nook Farm, the Clemens’s rented a house. In August 1873, they broke ground on their dream home, a 25-room, three-story, 11,500 square-foot ornate red brick house next door to Harriet Beecher Stowe. Designed by New York architect Edward Tuckerman Potter, the Clemens house cost a walloping $40-$45-thousand. (In 1870, the average 32’-by-40’ four-room home in the U.S. cost $700.)

The couple moved in in September 1874. Over the next 17 years, they happily reared three daughters there while “Mark Twain” enjoyed the most transformative and productive years of his life. Among the books he authored there were “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” “The Prince and the Pauper,” “Life on the Mississippi,” and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.”

In the wake of financial ruin because of an ill-fated investment in a typesetting machine, the Clemens’s vacated the house in 1891. The house was sold in 1903. Since its restoration and opening in 2003, the Mark Twain House has become one of Hartford’s most popular attractions.

A Visit to the Mark Twain House and Museum

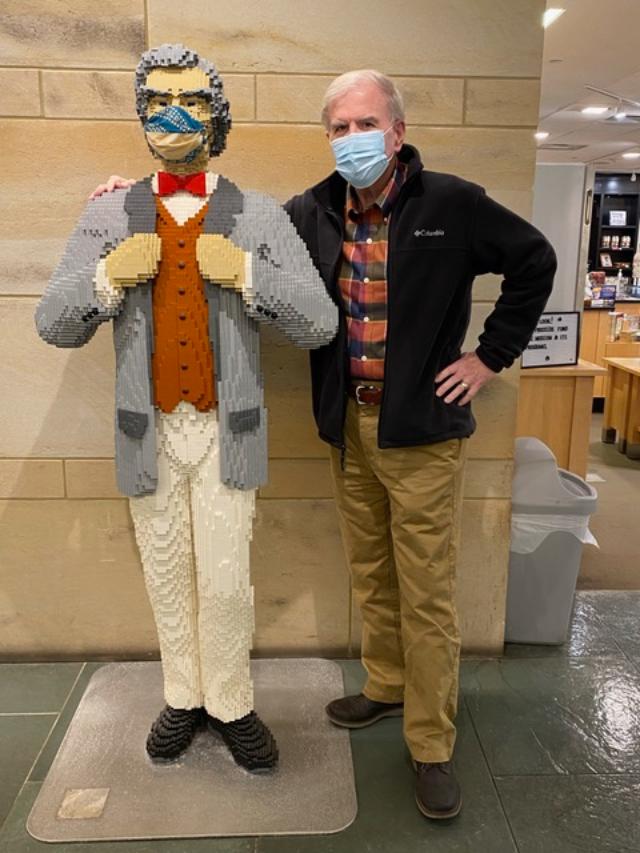

Lego Mark Twain and Jim Rapp

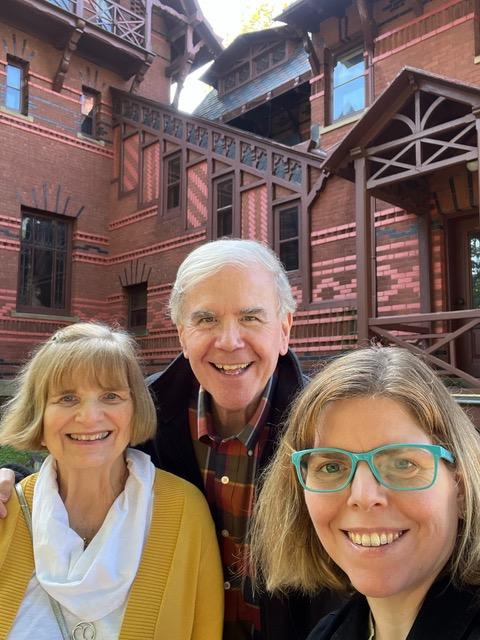

Martha and Jim Rapp and one of their three daughters, Elizabeth Dionne

In the Boston vicinity to visit family, we add a day to our trip to tour the Mark Twain House and Museum just two hours southwest. Even though it’s a school-day Tuesday during ordinary times, our daughter made reservations for the hour-and-fifteen-minute tour of Mark Twain’s house. A variety of tours is available, from a general tour to tours led by actors portraying important people from Mark Twain’s home life. Tours are limited to groups of 12.

Entering the museum, we are greeted by a six-foot-tall, 150-pound LEGO statue of Mark Twain, wearing a facemask. We’ve arrived an hour before our scheduled tour. It’s the perfect amount of time to pick up our tour tickets, view an excellent 23-minute video by Ken Burns, and visit an exhibit about the Clemens family’s life in Hartford.

As we tour the exhibit, I realize how little I’ve understood about one of America’s most iconic (yet banned) authors. Is it true, for example, that far from being a racist novel as recently charged, “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” was an attack on Reconstruction America? That Huck Finn was trying his level best to rescue a human being who post-Civil War America had abandoned?

I ponder Clemens’s words that Huck Finn was “a book of mine where a sound heart and a deformed conscience come into collision and conscience suffers defeat.” Did that collision occur as Clemens, who’d spent his childhood summers playing with children of slaves on his uncle’s Missouri farm, evolved into a man who recognized and confronted his own preconditioned biases? Were such deeds as his paying the Yale law school tuition, room, and board for one of the school’s first black students, Warner T. McQuinn, an act of contrition?

Time passes quickly. It is time to join our tour.

A Dark and Majestic Entry

The Mark Twain House has been designed to resemble a riverboat. Walking through the heavy front door, we find ourselves in a large and elaborate entry hall. The predominantly red receiving area with an imposing staircase, a carefully stenciled silver and black design, and a rare-at-the-time electric light strikes me as dark, majestic, and somewhat suffocating. Our tour guide tells us that in 1881 as Clemens’s writing paid off, his wife Livy commissioned one of the country’s most acclaimed firms, Louis C. Tiffany’s Associated Artists, to create exotic interiors for the main rooms on the first floor.

Tiffany’s artists drew from different parts of the world—Morocco, India, Japan, China, and Turkey among them. Each room—drawing room, dining room, library, conservatory, and a guest bedroom that served as a green room for family theatricals—has its own character. The effect is spellbinding enough that National Geographic once named the residence as one of the world’s Ten Best Historic Houses.

Impressive as the first floor is, I am relieved when we finally escape the exotic heaviness and move to the second and third floors. There, we get a much more intimate look into family life.

Stepping Out with Mark Twain

As enthralling as the second floor is—and I especially enjoy seeing the nursery the two younger Clemens girls shared with their governess and the schoolroom where the girls were home-schooled by the same governess and their mother, the third-floor billiard room most captures my imagination.

This is the man-cave where Clemens sequestered himself day after day to write, most often seated at a corner table to avoid distractions. This is where Clemens smoked between 20 to 30 cigars a day, nevertheless going on to live a long life. This is where Clemens entertained friends on Friday nights until the wee hours of the next day, shooting pool at the billiard table that dominates the room.

The billiard room opens to a balcony. Our tour guide tells us that if unexpected visitors arrived when Clemens didn’t want to be interrupted, Clemens would move to the balcony and instruct his butler to announce that he’d just stepped out.

A Heartbreaking Departure

As observant as Clemens was, his gift of accurately reading situations did not extend to investments. Betting heavily on the Paige Compositor, an invention that was supposed to revolutionize printing, he managed to lose his and his wife’s fortunes—$300,000, which is equivalent to $6 million today. Facing bankruptcy, the family vacated the house in 1891, moving to Europe. The plan was that Clemens would embark on a lecture tour, earn enough money to pay off his creditors, and eventually come home.

Any hopes he and Livy had of returning to their Nook Farm home were dashed in 1896, when their eldest daughter, Susy, died in the house from spinal meningitis. Heartbroken, the couple never lived there again.

Livy died in Italy from heart failure in 1904, a year after the sale of the Hartford house, and Samuel in 1910 at Stormfield, a new home he built in Redding, CT.

Homecoming

We return to Quincy the day after our tour. As we lug our suitcases into the laundry off the garage, I spot a counted cross-stitch that’s hung on the wall for years:

It’s the same quote that’s etched in brass over the fireplace in the library of the Hartford House: “The ornaments of a home are the friends that frequent it.”

I know I am home.

Martha Brune Rapp served as senior manager of strategic communication for Harris Corporation’s Broadcast Communications Division. Called to ministry in 2005, Rapp received a doctorate in preaching in 2018. She is a certified spiritual director and author. Her first book, “Conversations with Benjamin: A Spirituality of Preaching that Heals,” was published by Wipf and Stock of Eugene, Ore., earlier this year.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.