Taming the Upper Mississippi, Chapter 3: Navigation and flood control

EDITOR’S NOTE: Muddy River News has received permission to reprint reviews and chapters from the book, “Taming the Upper Mississippi: My Turn at Watch, 1935-1999,” written by Janice Petterchak. The book reflects on flood protection, navigation and the environment on the upper Mississippi River through the eyes of Quincy engineer William H. Klingner. You can read the entire series here.

The first half of the 20th century saw huge changes and improvements in both flood control and navigation for the entire length of the Mississippi River.

In response to railroad baron James J. Hill advocating for the abandonment of river projects, an association of delegates from Illinois, Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota and Wisconsin met in Quincy in 1902 to advocate for a six-foot channel between Minneapolis-St. Paul and St. Louis.

One member said, “We regard the Mississippi River of such mighty value in our occupations and to our respective communities that we do not propose to have it slandered or permit it to be neglected.”

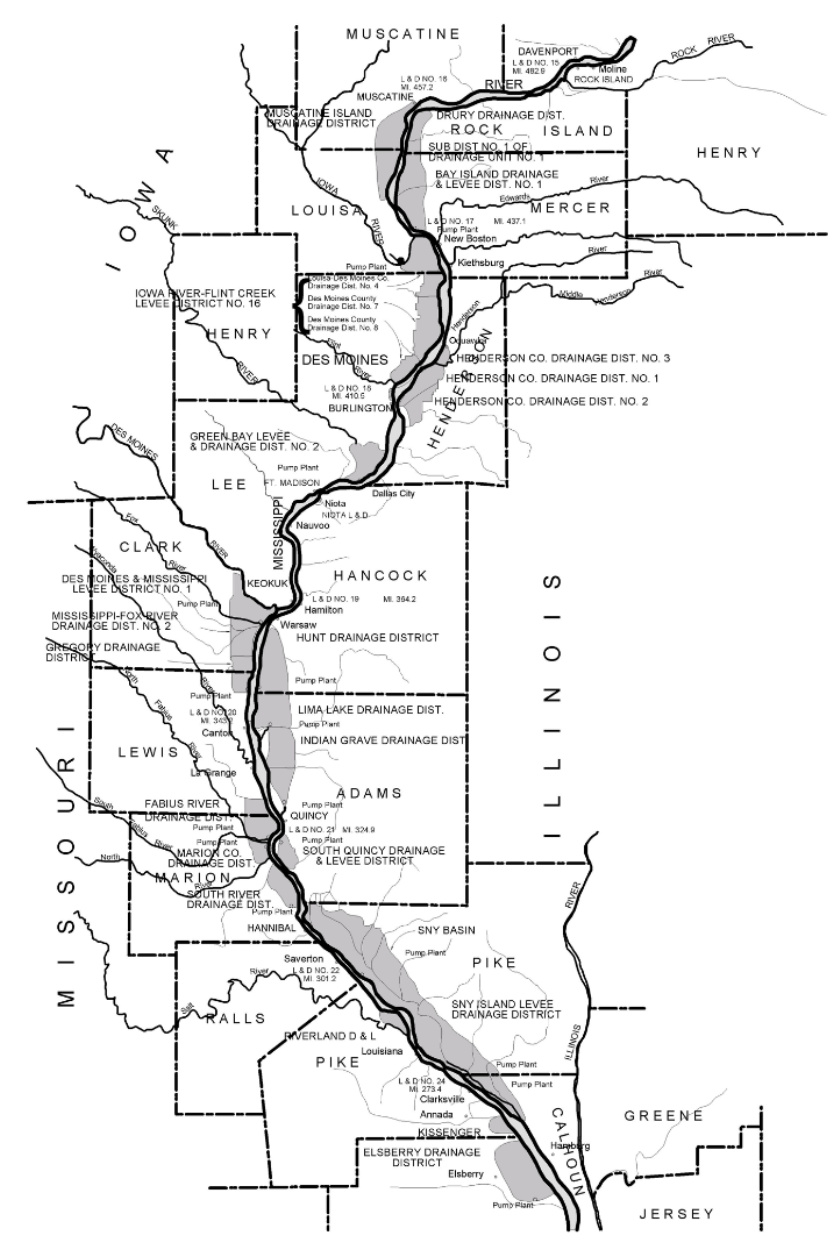

These early years of the 20th century also saw completion of the levee districts along the Mississippi River from St. Louis to the Wisconsin border, mostly funded locally and designed to the high water of 1851.

In the lower Mississippi, the flood of 1927 flooded 26,000 square miles. — an area roughly equal in size to Massachusetts, Connecticut and New Hampshire combined. Congress acted quickly and passed the Mississippi River and Tributary project, resulting in a major flood control project for the lower valley from Birds Point, Mo., near Cairo, to New Orleans. This project remains in the president’s budget and is funded annually for ongoing maintenance and improvements.

It was in this same decade that engineers in 1929 concluded that a nine-foot channel for the Upper Mississippi from St. Louis to Minneapolis-St. Paul was feasible. Congress passed the 1930s River and Harbors Act, authorizing construction of 26 locks and dams, approximately 25 miles apart. The stairway of dams extended for 660 miles and a rise of 420 feet.

The Clarksville, Mo., lock and dam was the last one completed in 1940. This furious pace of construction had as many as 13,000 men working under the Public Works Administration and under the design and instruction of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Although strongly supported by the communities and agricultural interests in the Upper Mississippi Valley, the locks and dams raised water elevations against the main stem levee districts. As a result, gravity drainage was often cut off completely or pumping costs increased due to the higher water elevations. In addition, the pools reduced the level of protection for these Upper Mississippi River levee districts.

Congress instructed the Corps of Engineers in 1937 to determine any adverse effects to the levee districts. Seepage damages were calculated and the need for additional flood control led to a series of flood control acts to mitigate what was then understood as damage. However, the level of mitigation soon proved to be inadequate for the Upper Mississippi.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.