Crim: Few did more to make Northeast Missouri and West-Central Illinois a better place to live than Tom Oakley

Fifteen months after retiring as executive editor of The Herald-Whig, I was sitting on the back porch of a rental house we were remodeling, contemplating whether to knock off for the day or go inside to do a little more work, when my cellphone rang.

It was Tom Oakley.

After quickly exchanging pleasantries, he explained he was preparing to testify before the Illinois Senate Transportation Committee in support of a capital bill that would increase transportation funding.

He said he was being allowed only so many minutes to speak (how many I don’t remember) and felt what he had prepared was too long and not organized well enough. He wondered if I had time to take a look and tighten it up to ensure he could get key points across to lawmakers in his allotted time.

“You’ve always been good at that sort of thing,” he said.

Sure, I told him. Email it, and I will be happy to go through it when I get home.

“When do you need it?” I asked.

“First thing tomorrow morning,” he said. “I need to send copies to some people.”

An urgent request with a tight turnaround time. It reminded me of an observation the late Mike Hilfrink, my boss for 28 years at the newspaper, once passed along.

“Old editors never really retire,” Mike said. “With Tom, you’re only a phone call away.”

I will miss those phone calls.

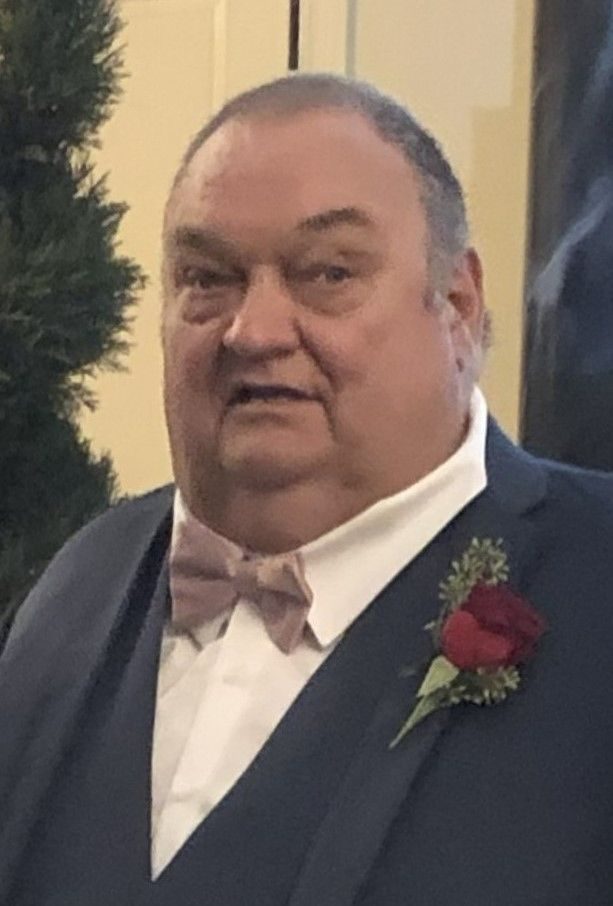

Tom Oakley died Wednesday, a little more than two months before what would have been his 90th birthday. The news was shockingly sad, because he was one of those larger-than-life figures we always felt would live forever. It made a cold, rainy day drearier.

That’s because you would be hard-pressed to find anyone who did more during the last six-plus decades to make West-Central Illinois and Northeast Missouri a better place to live than Thomas A. Oakley.

Younger people living here today take for granted the ability to merge onto a four-lane interstate highway and drive with ease to Springfield, St. Louis, Kansas City, Iowa City or Chicago to shop, visit friends or relatives, see a doctor, or attend a concert or sporting event.

Old-timers will tell them it hasn’t always been this way. Far from it. The ease and safety of everyday travel, as well as the improved efficiency for businesses moving their products, is because the vision and persistence of Tom Oakley helped make those hundreds of miles of highways possible.

It took more than 50 years, after all, for the Chicago-Kansas City Expressway to become a reality. The Central Illinois Expressway (now I-72) was 30 years in the making. The Avenue of the Saints took almost three decades to complete.

A lesser man may have given up after obstacle after obstacle was thrown in front of him.

Not Tom. Taking “no” for an answer wasn’t in his DNA.

Like to take the train to Chicago? Or fly out of Quincy Regional Airport? Tom beat the drum for those amenities, too.

Those are just the headlines, however.

Tom and the rest of the Oakley and Lindsay families have been strong supporters of local elementary and secondary education, Quincy University, the performing arts, philanthropic giving, economic development – anything and everything, really, that would make Quincy and the surrounding area a better place to live, work and raise families.

They used their megaphones, The Herald-Whig and WGEM television and radio, to not only report and analyze but to promote and influence.

With his towering stature and booming voice, Tom could be intimidating. Just ask the many governors, senators, congressmen, city and business leaders, school board members and transportation officials who sat across from him in the board room on the second floor of The Herald-Whig building.

He expected them to be as prepared as he always was to discuss an issue, project or candidacy. To him, what mattered most, was what was best for Quincy and the region. He continued to work tirelessly to achieve that outcome at an age when most would already have taken the exit ramp into retirement.

He was equally demanding as publisher of The Herald-Whig. It sometimes took a while – especially when you’re young and his name is at the bottom of your paycheck – to realize he just wanted us to be the best we could be, to be resilient and work for the readers we served, no matter the hurdles.

He acknowledged our successes and scrutinized our failures, enabling us to learn from them.

At the same time, Tom knew the names of every employee in the building and what their jobs were and spoke each time he encountered them, often at length. He knew about your spouse and kids. He personally delivered Christmas bonus checks, when those were a thing, with a handshake and a thank-you.

Tom also was a sportsman and ultimate competitor. He loved to hunt, golf and follow Quincy High School and Quincy University basketball. He often would make his way to the sports department to rehash games or tournaments, offering and seeking insight.

Along with those who preceded and followed me as sports editor, I was given many opportunities to travel to cover PGA Tour tournaments, including the Masters. Tom believed it was important for the newspaper to provide coverage of native son D.A. Weibring.

Once, as a young sportswriter, I was assigned a feature story on skeet shooting. Tom learned of it and thought the best way for me to write that story was to experience the sport firsthand by shooting with him and his buddies at the West Quincy Gun Club.

Seeking to avoid what I surely knew would be an embarrassing experience, I tried to point out that (A) I was quite comfortable writing the story as is, (B) I had never fired a shotgun in my life and (C) I was pretty sure accidentally wounding or killing my publisher would make the front page the next day, not the sports section.

Tom, of course, would have none of it.

So we met at the club the next Saturday morning. He gave me a few pointers, loaded his shotgun and handed it to me. With every ounce of courage I could summon, I said a prayer, yelled “pull,” closed my eyes, pulled the trigger and miraculously hit the first clay target.

Of course, that was the only clay target I hit that day. But no one died, and I still had a job the following Monday.

And I learned you don’t say “no” to Tom.

During my last several years with the newspaper, with Tom no longer serving as president and CEO of the company, we collaborated on editorials and the many projects he was involved in. Few were the days when we didn’t talk, either face-to-face in his office or mine, or by phone.

I gained a greater appreciation for his firm grasp on issues, how using certain words or phrases would better make a point and his tenacity for getting things done. Most of all, I got to see how much he cared – for his hometown, his newspaper, his family and the people around him.

So, I never hesitated when Tom would call asking for assistance after I had left the newspaper. He was still out front, leading the charge as he always did. It felt good to be part of that again.

The last time we spoke was in December. He called to congratulate me on being selected for the Illinois Basketball Coaches Association Hall of Fame for my work decades ago as a sportswriter.

We chit-chatted for a bit about the years we worked together, and then he said he had to go. He was working on a project he couldn’t tell me about just yet and had a meeting scheduled in a few minutes.

I mentioned we should have lunch one of these days.

“I would like that,” he said.

Life, as it often does, got in the way, and it never happened. Now it never will. Who knew time would suddenly run out on a man with so much left to accomplish?

To borrow a phrase, Thomas A. Oakley was an original, a shooting star. We will live in his afterglow for a long time.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.