Executive order means disabled workers will get minimum wage in state jobs; Transitions director worried about future legislation

QUINCY — Transitions of Western Illinois recently renegotiated its contract with the Illinois Veterans Home to comply with an executive order signed in October by Gov. J.B. Pritzker that prevents companies contracting with the state from paying disabled workers less than the minimum wage.

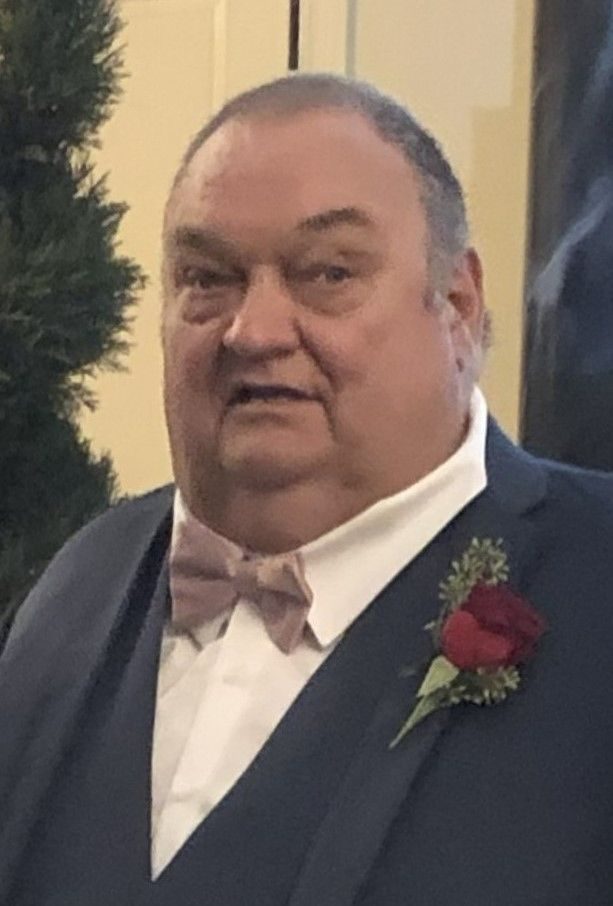

Executive director Mark Schmitz says the order will help many of Transitions’ clients, but he’s worried about potential future consequences.

Pritzker told Capitol News Illinois he took the action as part of a broader effort to push federal lawmakers to change the law that allows companies to pay disabled people less than the minimum wage.

“With this change, every contract the state of Illinois enters from now on will ensure that people with disabilities receive a wage that affirms the value of their work,” Pritzker said.

The order only applies to companies contracting with the state. Provisions in the federal Fair Labor Standards Act section 14(C) allow employers to obtain a certificate to hire disabled individuals and pay them less than minimum wage. Pritzker’s executive order doesn’t prevent private companies in Illinois from taking part in that federal program.

Advocacy group says disabled workers are paid pennies on the dollar

Karen Tamley, president and CEO of the disability advocacy group Access Living, told Capitol News Illinois the federal 14(C) program “allows disabled workers to be paid pennies on the dollar for work that’s often performed in segregated or sheltered settings.”

“And if we can all imagine the sting of taking home just a few dollars for two weeks work, that’s the reality for many in our community,” she said.

Transitions, 631 N. 48th, is a charitable, not-for-profit agency providing mental health, rehabilitation and educational services. Transitions has several contracts with the state. The only one to be renegotiated because of Pritzker’s order was with the Veterans Home, which contracts for laundry service.

People working under the federal 14(C) program at Transitions are paid on a piece rate instead of minimum wage, which will rise $1 to $12 per hour in 2022.

“They’re getting paid based on the amount of productivity they have for a given job,” Schmitz said. “We do time studies to determine how long a particular job would take the average worker. If a person we employ has disabilities and does that same job, we pay them based on a proportion of the full rate based on the number of items of work they’re able to do in the same amount of time.”

Some want federal 14(C) program changed or discontinued

Transitions has contracts with about 25 local companies. About 100 clients work at Transitions — some one day per week, others as many as five days per week.

Schmitz says he’s heard the concerns of advocates who want the federal 14(C) program changed or discontinued.

“Some people believe this is a way to pay someone too little and take advantage of someone,” he said. “But like a lot of things in life, two things can be true at one time.”

Schmitz, the executive director at Transitions since 2017, said sheltered workshops were set up across the country when federal law was passed in 1938. They provided a temporary launching point for disabled workers before allowing them to “move into competitive and integrated employment.”

He says some workshops have “probably” taken advantage of the law, becoming big profit centers.

“That’s never been the case with us, at least not in the recent years,” Schmitz said. “This has always been at best a break-even proposition, and usually it’s a financial loser.”

Transitions was founded in 1955 as the Adams County Mental Health Center. Schmitz said it started providing shelter work because opportunities for people to work at their level of disability were not easily found.

“The 14(C) certificate allowed us to create a space for them,” he said.

Schmitz wants to make sure all disabled workers still have opportunities

He isn’t against changing how disabled people are paid or where they find work. He just doesn’t want to leave anyone out.

“That’s my concern about the plans to eliminate 14(C). What’s your plan to replace it?” Schmitz said. “Illinois doesn’t have the best history in providing services for people with developmental disabilities. It has multiple federal lawsuits filed against it for being inadequate in its services. So when the state says, ‘Oh, trust us. We’re going to take care of those people who are the most severely disabled so they still have an opportunity to participate,’ I wonder about that. The advocates of discontinuing 14(C) are concentrating on people in that upper range, people who probably could seek community employment and have a good job match.

“14(C) allows us to seek jobs people can do, even if they can do it on a very limited basis. There’s a pride in participating in the world of work. If you employ someone who has a disability for a job, and you’re employing them at 10 percent of what your other employees’ productivity is, that’s going to be hard for an employer to do. An individual’s options going forward, if 14(C) is totally eliminated without something to replace it, are either to sit at home or be in a day program being told you can’t work.”

Taylor told Capitol News Illinois advocates are calling on the General Assembly “to take the next step and eliminate the use of subminimum wage for people with disabilities in all jobs.”

More than 100 Illinois facilities had 14(C) licenses in July 2018

Advocates said a review of Illinois records in 2019 showed some certificate holders paid wages far lower than $1 hourly. They estimated more than 100 facilities had 14(C) licenses as of July 2018, employing more than 10,000 disabled individuals.

Schmitz said the problems businesses are having in finding employees could possibly be answered by hiring Transitions clients. He said Transitions helped 49 people with disabilities find jobs in the community last year.

Starting in January, Schmitz said Transitions can take groups of three to six people with disabilities to job sites.

“They have to be paid a minimum wage, and they have to interact with other people who aren’t disabled,” he said. “They can’t be segregated somewhere, but we can send a job coach along. So it is a different model. Rather than provide that work opportunity on our site, we’re providing it at the employer site.

“If businesses that offer regular work involving kind of repetitive types of activity, we might fill that need. And (disabled workers) don’t want to be pigeonholed only into doing janitorial or small parts assembly. We’re interested in finding opportunities that give us more options to give folks.”

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.