Hannibal native makes first official visit home since becoming Missouri’s lieutenant governor

HANNIBAL, Mo. — Missouri Lieutenant Governor David Wasinger paid a visit to his hometown of Hannibal on Thursday, making several pit stops throughout the city on his first official visit since becoming the first Hannibal native elected to the position in November.

When asked if his perspective on the city has changed now that he holds the responsibilities of public office, a smile swept across his face.

“It hasn’t changed at all,” he said.

Though Wasinger has lived in St. Louis County for several years, his communications director said he still speaks of Hannibal often and keeps several photos of the city on display on the walls of his office.

“I’ve always loved Hannibal,” he said. “We’re going to be fighting for all Missourians, but Hannibal has a close place in my heart.”

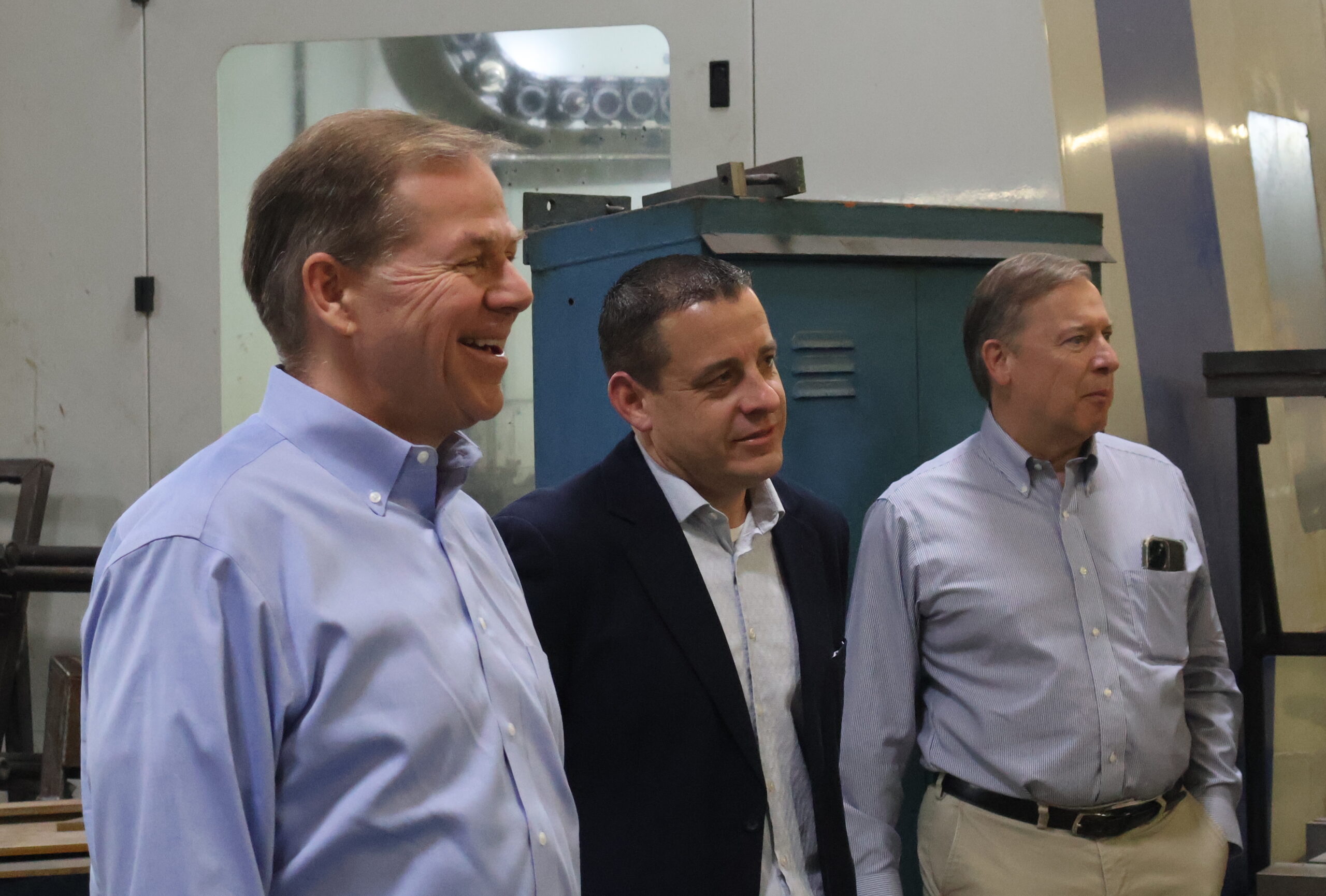

Wasinger began his hometown tour at Hannibal Machine, a manufacturing company owned by the family of Scott Haycraft, 1st Ward Council Member for the Hannibal City Council. Mayor Darrell McCoy also attended, along with 5th Ward Council Member Michael Fleetwood and State Rep. Louis Riggs (R-5).

“We’d like to bolster great Missouri companies like Hannibal Machine,” Wasinger said after touring the facility. “We’ve got a window of opportunity, I think, here with President Trump in office wanting to boost manufacturing and bring it back to the United States. We’d love to have it come back to northeast Missouri and the Hannibal area.”

Hannibal and the greater northeast Missouri region has seen several factories close since mid-20th century.

International Shoe Company reported that its Hannibal factory had produced roughly 100 million pairs of shoes and paid $40 million in wages between 1928 and 1938, supporting many families through the darkest days of the Great Depression. Hannibal historians reported that shoe production was the city’s second largest industry at one point, but all of the factories had closed by the early 1980s.

Buckhorn Rubber Products was sold to Zhongding Sealing Parts Co. Ltd. in 2009. Consolidation efforts led to the closing of the Hannibal manufacturing plant in 2017, resulting in the loss of 119 jobs.

According to the Kansas City Star, layoffs and facility closures led to the loss of more than 5,000 jobs in Missouri throughout 2024, down from nearly 6,700 job losses in 2023.

In addition to advocating for a return of manufacturing enterprises, Wasinger has stated several times that the aging population is one that is especially close to his heart.

“Seniors are real high on our priority list,” he said. “I’ve got a mother who’s had some health problems because she’s a senior.”

Additionally, NPR’s St. Louis station reported before Wasinger’s victory that his mother had a negative experience living in a senior facility.

“If you have someone with memory care issues who does not have an advocate, I can only imagine what’s taking place in some of these senior care facilities,” Wasinger said in the piece.

Wasinger announced last month his intent to establish an advocate for senior citizens through his office — a position mandated by Missouri law in the 1970s that the state legislature has largely disregarded. (Wasinger said he didn’t believe it was intentional but merely an oversight.)

The “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” passed last week in the U.S. House of Representatives, outlines hundreds of billions of dollars in cuts to Medicaid over the next decade. It is not anticipated to pass in the Senate without alterations, and an op-ed in the New York Times by U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO) in defense of Medicaid indicated he would not vote in support of any bill that included such cuts.

According to health reporting organization KFF, roughly 80 percent of the state’s Medicaid funding is supported by the federal government. Of that, 27 percent goes towards long-term care. More than two-thirds of the state’s nursing home residents can obtain their care through Medicaid.

Seven in 10 Medicaid recipients are working at least part-time, and the majority of others are full-time caregivers or students, retired or disabled.

Though only about eight percent of Medicaid recipients don’t work and don’t qualify for an exemption, an estimated 28 percent of recipients (about 91,000 Missourians) are at risk of losing coverage.

When asked how the state planned to cover the potential loss of federal funding, Wasinger said it was still too early to tell and that he’ll be watching to see “how things fall out” in the Senate.

Wasinger ran as a MAGA-aligned outsider ready to shake things up in Jefferson City as much as President Donald Trump promised to shake things up in Washington, D.C. The strategy proved successful, as he narrowly won the Republican nomination against State Sen. Lincoln Hough (R-30) in the primaries, and then defeated Democratic State Rep. Richard Brown of Kansas City by 15 percentage points in the general election to secure his first publicly elected position.

He’s the first lieutenant governor since Mel Carnahan, who held the role from 1989 to 1993 before going on to become governor, to occupy the office without first serving in the Missouri Senate.

The role was most recently previously occupied by current Gov. Mike Kehoe. Before Kehoe, former Gov. Mike Parson served in the role briefly before moving on to serve as governor from 2018 to 2025.

The Missouri Independent reported earlier this month that Wasinger had already begun to disrupt the status quo in the state’s capitol, as he “recognized himself to speak” on the Senate floor regarding the state’s budget. Sen. Cindy O’Laughlin (R-18) claimed he was out of line by exercising “a right reserved for senators.”

Before becoming lieutenant governor, Wasinger ran a failed campaign for state auditor in 2018 and served on the Board of Curators for the University of Missouri, his alma mater, from 2005 to 2011.

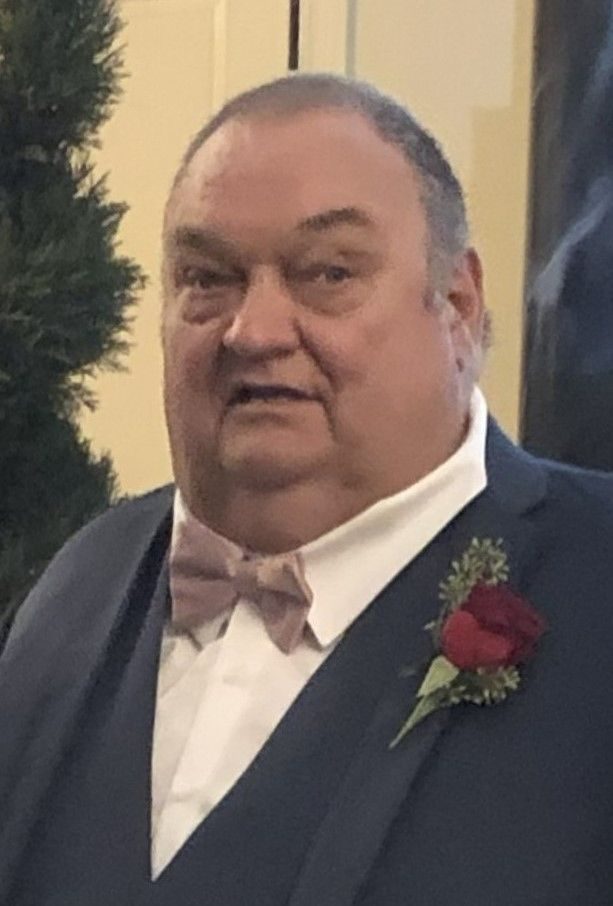

Other stops during Wasinger’s visit included Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Hannibal Regional Hospital and the Mark Twain Boyhood Home. He concluded by giving a keynote speech during a Lincoln Day dinner hosted by the Marion County Republican Central Committee at the Hannibal Nutrition Center, where McCoy presented him with a key to the city.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.