Natural wonders and historical irony: A Quincyan explores South Dakota

The most diverse geography, geological formations and assemblage of dinosaur fossils in the United States unfold across the state of South Dakota — from the Eastern Plains and cornfields, to the deserts of the Badlands, to the mountain ranges near the Wyoming and Montana borders. In Spearfish, temperatures dropped 49 degrees in only two minutes as Chinook winds blew off the Rockies. The Black Hills embed 2 billion-year-old pre-Cambrian era igneous and metamorphic rocks that are among the oldest in the world.

Human history is just as vast and diverse. Beneath this land where people lived for 12,000 years before European incursion, where wagon trains traveled and bison grazed, where cowboys roamed and pioneers settled, now lies the nation’s largest stockpile of minuteman missiles. A nuclear attack would most likely target this state first. Life in South Dakota, though, continues amiably with one of the nation’s highest rates of population growth and levels of happiness.

Paleontologists may smile at the state’s motto, “Under God, the People Rule,” in this locale where dinosaurs dominated for 200 million years. The state’s fossil is the Triceratops, a large-horned vegetarian dinosaur that existed in the Hell Creek Formation. Later the first human inhabitants, Indigenous Native Americans, lived here for a dozen millennia before pioneers brandishing belief in a divinely ordained “Manifest Destiny” destroyed their lifestyle with force and a host of novel immune-resistant diseases.

This ancient land, which much later became known as South Dakota, contains a large part of Earth’s record of life and the mythology of the 19th century American Frontier that has shaped our national character. On extensive explorations of this state, I discovered more of the historical legacy of the Earth’s story and our country’s.

One needs to return to the very beginning to support this bold statement, and the best place to start is in Hill City’s Dinosaur Museum. Most skeletal remains of this once-dominant species (like humans today) are found in this state. The museum curator eagerly tells visitors that dinosaurs ruled Earth for more than 600 times as long as humankind has existed here, and their extinction was part of the natural rhythm of all life. Of the 4 billion species of life that have existed on Earth, 99 percent have become extinct. Humanity is not an exception, and it may well be suicide from environmental destruction or nuclear holocaust.

He pauses long enough for guests to gaze awestruck around the museum. On a 24-hour clock, he continues, if Earth formed at midnight and the present moment is the next midnight, modern man arrived on the scene at 11:59 and 59 seconds p.m. Most scientists estimate that in a mere one million years (4/1000th the age of Earth) all life here, human and other, will be extinct. The Earth will continue long after the drama of living is over. Visitors usually leave humbled and stunned by the recognition of their infinitesimal place in the universe.

Outside of these dizzying dimensions of magnitude, shift awhile to the human inhabitants who first called this place home: Indigenous People of North America. Their lives were far from idyllic: high mortality and disease rates plagued them and they often struggled to survive. Fighting with other tribes occurred and, as in every society, internal conflicts arose. However, they revered the land and honored its bounty and beauty. Bison provided much of their sustenance for food, clothing and shelter. When they took an animal’s life, they prayed to its spirit and saw their killing as ritual sacrifice and sacred offering. They respected the circle of life, found solace in a balance with nature, and did not try to subdue the Earth.

In the early 19th century, French explorers entered this land, known then as the Dakota Territory, and claimed it for their Mother Country. They briefly ceded it to Spain before regaining control and becoming part of the Louisiana Purchase made by the U.S. government from France in 1803. The Lewis and Clark Expedition explored this territory, which later became a center of fur trade and cattle ranches. Tensions between the northern and southern parts of the Dakota Territory, largely brought about by railroads which connected the two sections to different commercial hubs, led to the division and statehood of both North and South Dakota in 1889 under President Grover Cleveland.

Native people had no say in these transactions and abhorred the notion that land could be owned, partitioned or purchased. When later 19th century pioneers recklessly destroyed the herds of bison that sustained their lives and usurped the land for homesteads and the spread of “civilization,” these “savages” were bewildered and stunned.

Mythology of “How the West Was Won” is deeply ingrained in movies and Western novels and has whitewashed what many historians call “genocide” and the most shameful chapter in the American story. As part of an Indian Relocation Program, the U.S. government signed the Treaty of Laramie in 1868 and placed Lakota Sioux on a reservation in the Black Hills. The Sioux used the land for hunting, ceremonies and burials. The nation broke this treaty in 1874 when the Custer Expedition discovered gold here and President Ulysses S. Grant sent in the military to reclaim the land.

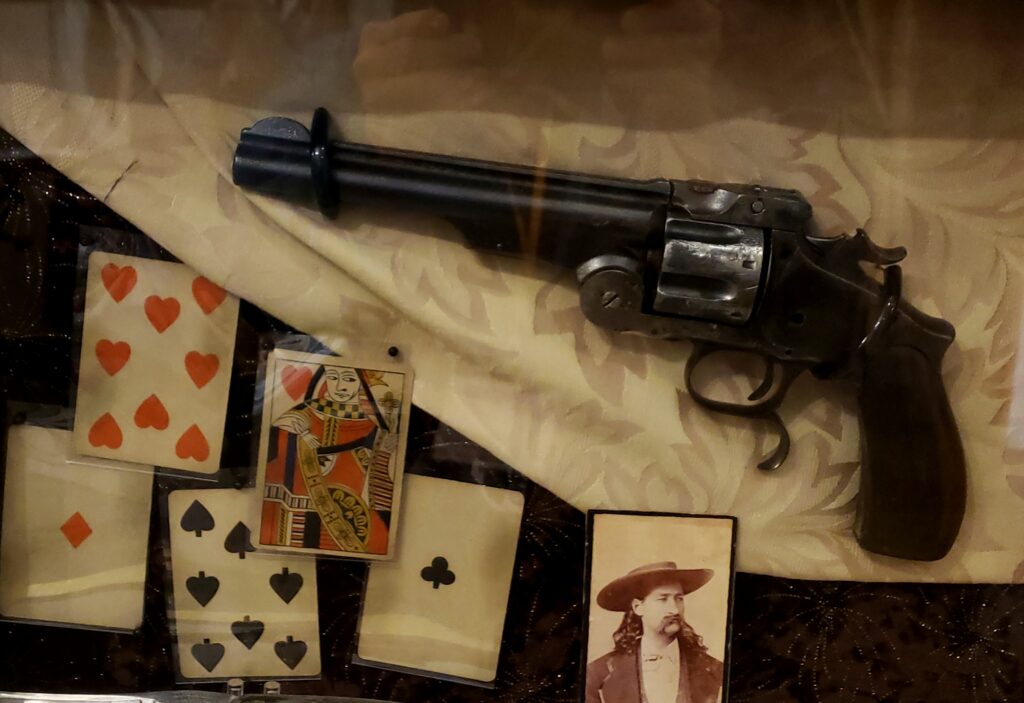

Deadwood became the center of this Gold Rush and between 1876 and 1879 its population swelled to 25,000, with miners, fortune-seekers, and entrepreneurs eager to relocate in this remote part of the state. The 10 square miles around Deadwood would eventually yield the largest gold reserve in the Western Hemisphere. Along with the fever for riches came crime and widespread lawlessness. The likes of Wyatt Earp, Calamity Jane, and Wild Bill Hickok made this a place of sudden violence, where players took card games and roulette as seriously as the lust for gold.

Gambling remains legal in present-day Deadwood and on many Native American reservations. The downtown Brothel Museum showcases the history of the “World’s Oldest Profession,” which continued to operate here with law’s full sanction until 1980. A reenactment of the killing of Wild Bill Hickok by Jack McCall in the Nuttal & Mann’s Saloon is staged daily for the entertainment of visitors.

The cowboy image is as iconic as John Wayne, Buffalo Bill Cody, and the Marlboro Man riding a Palomino into the sunset… and just as illusory. Natives rarely attacked wagon trains—which oxen mostly drove and not horses. Thousands of caravans crossed the Oregon Trail, and few fatal skirmishes and firefights occurred compared to deaths from disease and accidents. Pioneers used wagon circles to keep draft animals inside and not invaders out. American cowboys themselves originated with Mexican “vaqueros” and some were Black, Oriental and first-generation immigrants. Only a foolish cowboy would ride a horse during a gallop with holster and gun, lest the firearm discharge. A cowboy’s work was grueling, dirty, and hazardous, with poor food and little pay. Most cowboys only lasted a few years and would be aghast at the glamour given them in our popular media.

While the state denigrated Indigenous people, it granted women suffrage in 1918, one year before Congress ratified the Constitution’s 19th Amendment. South Dakota also gave women the opportunity to earn a living outside of marriage and a considerable amount of legal parity with men, including the right to file for divorce on her own. The state established equal pay for female teachers and laws against domestic battery during an era when a man could often assault and abuse a woman (even one not his wife) without legal consequences. Many single women opened businesses here and labored outside of traditional roles of midwife, domestic and seamstress. Some even joined ranches and cattle ranges alongside cowboys.

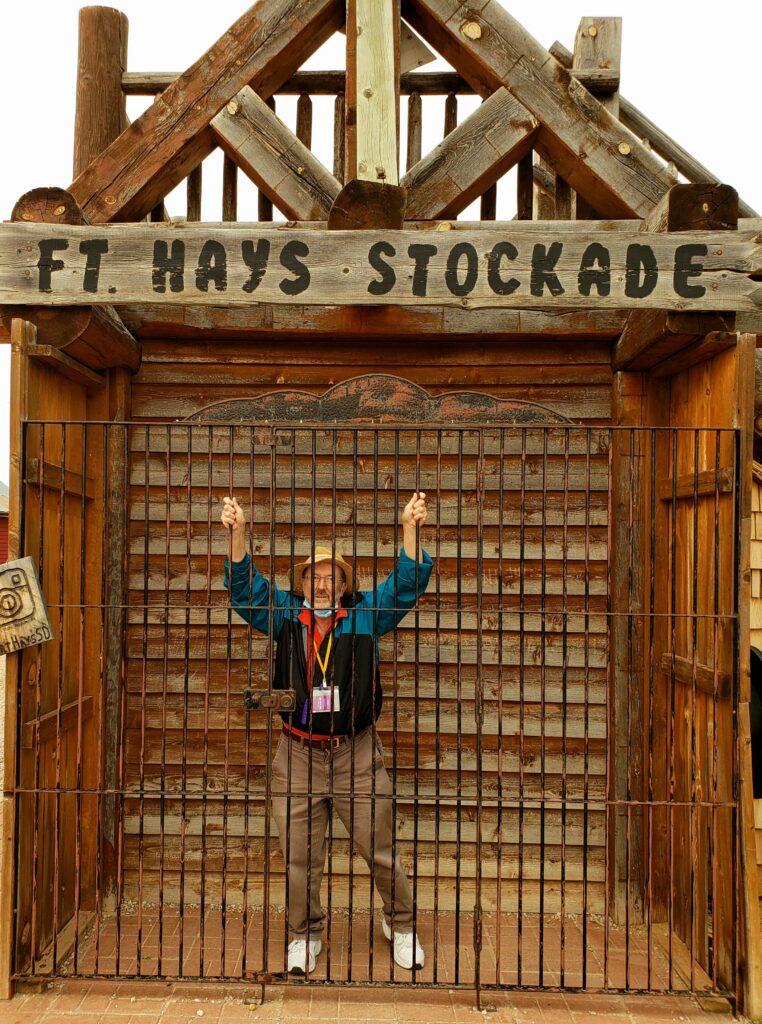

Along with showcasing the evolution of farming (the real oldest profession), the Fort Hayes Living History Museum features a military stockade. Officials held prisoners in these outdoor cages and fed them bread and water in enclosures without enough room to lie down and the ground as a toilet. Guards often beat prisoners, sometimes ruthlessly, and shackled unruly ones to the bars. The Constitutional interpretation of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishment” has changed dramatically over the years, from when the justice system wanted incarceration to be painful and the notion of “rehabilitation” and “reform” as remote as the belief that “Indians” were equal to White men.

The amazing-looking Corn Palace — made entirely out of corn cobs and kernels — rises over the town of Mitchell like a corn stalk pumped full of anabolic steroids. Unbelieving visitors often place their hands over the billions of kernels to make sure that they are not synthetic. Perhaps even more astonishing is that in the early 20th century residents built several corn palaces across the state offering homage (and enticing people to relocate here) to South Dakota’s most abundant and profitable crop. Domesticated by Indigenous people in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago, corn — also known as maize — is a staple grain crop for much of the world.

Painstakingly constructed corn kernel mosaics of George McGovern (the state’s former senator and 1972 Democratic presidential candidate), Wild Bill Hickok, Mount Rushmore and many more local portrayals fill this architectural wonder. The Corn Palace eagerly proclaims that South Dakota leads the nation in ethanol production and in 2025 will be one of eight states to sell gasoline year-round with more ethanol in it. The town of Mitchell itself smells like popcorn.

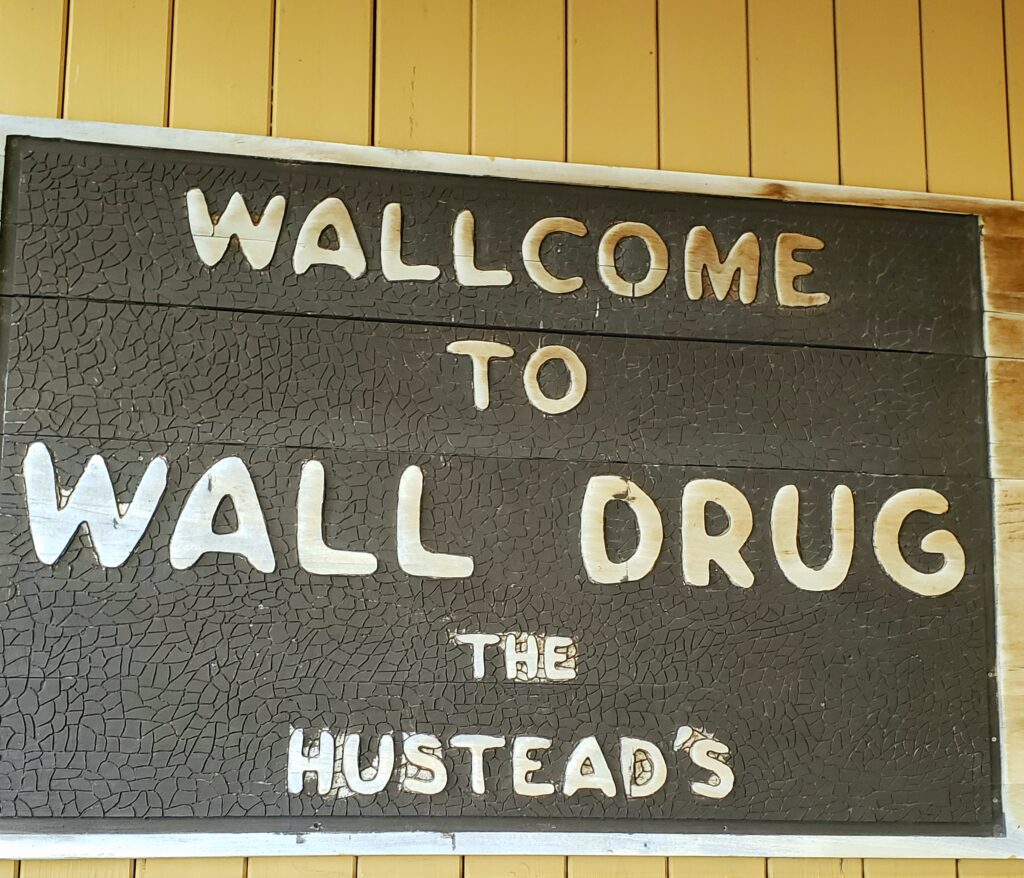

For hundreds of miles in all directions, signs proclaiming the distance to Wall Drugs dot the landscape on billboards, signs, and makeshift posters stuck on barns and telephone poles. They all point to what is seemingly the mecca of shopping destinations. Rarely has an advertising campaign by a stand-alone local store been so successfully promoted. Even people who have never set foot in South Dakota have heard the ubiquitous question: “How many miles to Wall Drugs?”

Upon arrival, this sprawling 76,000-square-foot store, which includes a restaurant and Western art gallery, consists mostly of overpriced items found less expensively in any Walmart or Target. This store, which gained its notoriety for giving free ice water to thirsty tourists headed to the newly opened Mount Rushmore site, is filled with so many novelties, knickknacks and curios that it looks like a bargain basement in a thrift store.

For example, a battery-powered coyote (the state animal) that raises its head and howls; a scale-model florescent dinosaur advertised to “Bring Jurassic Park Into Your Living Room”; and Buffalo-shaped corn-on-the-cob holders to “Let You Eat Corn Like a Cowboy.” Customers frantically search for items promoted to be at the Rainbow’s End. One rack of clothing has sweatshirts emblazoned with a Winchester rifle and the caption “How the West Was Won” next to those with images of the Crazy Horse Memorial.

Sturgis reigns as the motorcycle capital of the U.S. and the world. This is an unlikely place where since 1938 as many as 740,000 passionate cyclists have descended on this town of 7,000 during the annual Sturgis Festival to party and celebrate their lives on these two-wheeled machines. The town fathers have sometimes tried to end this festival but have been overruled by the Chamber of Commerce and local businesses, who welcome the added revenue and tolerate drunkenness, unbridled lust and occasional vandalism and fights. South Dakota, with its vast spaces and winding hills, is a motorcyclist’s dream of open roads and freedom.

This is a largely conservative state and, intriguingly, many motorcycle gangs and clubs hold this same political stance, often sponsoring rides and rallies for right-wing candidates. This is a far cry from the Easy Rider Days of the 1960s, but a new generation of cyclists has arrived on the scene listening to a different drummer and carrying a new banner.

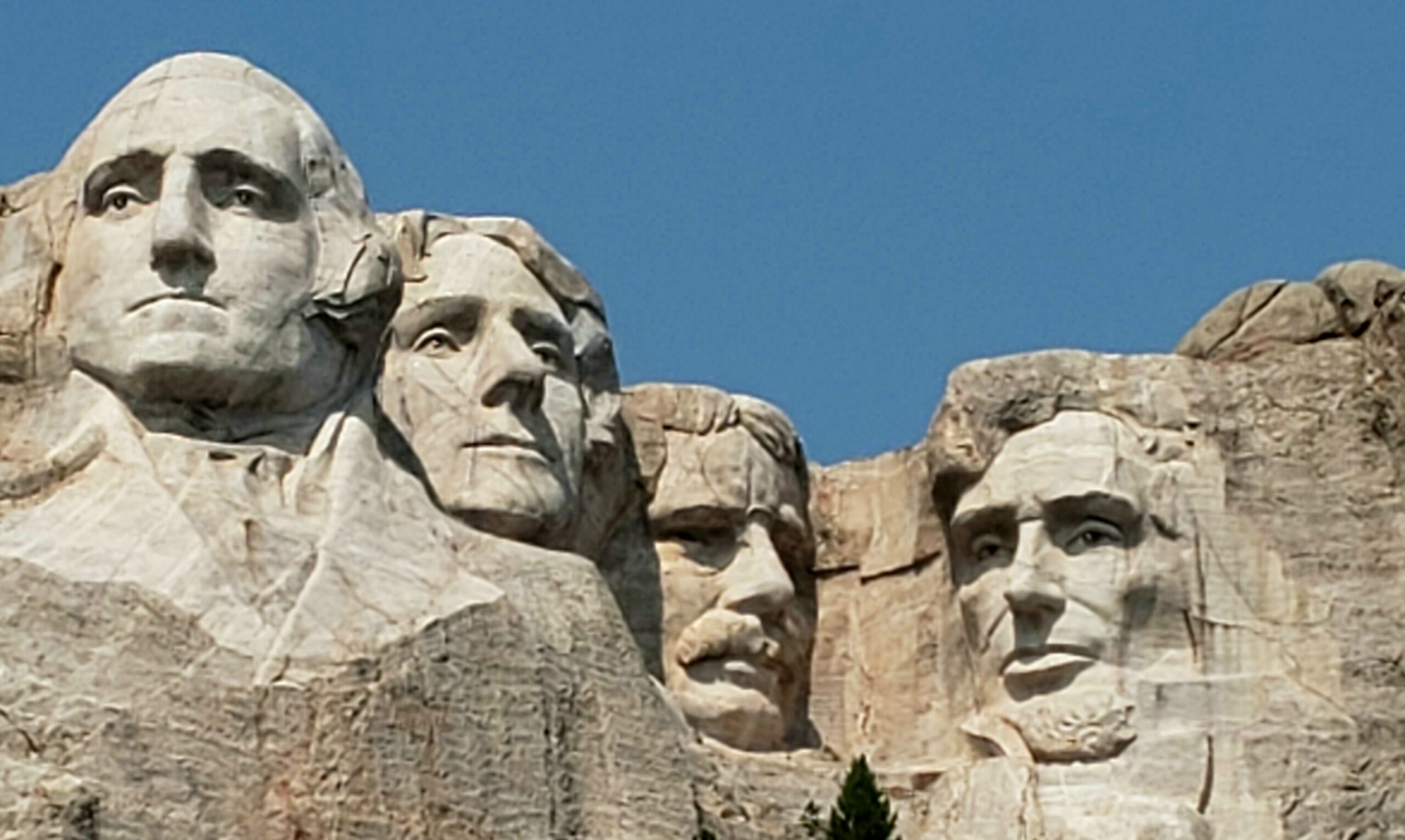

Originally conceived by state historian Doane Robinson as a monument to Western heroes, including Native Americans, and modeled after a similar tourist attraction in Tennessee, the “Story of Democracy,” better known as “Mount Rushmore National Monument,” is the iconic image of South Dakota. Sculptor Gutzon Borglum headed this project, which began in 1927 and completed in 1941. His workers carved the likenesses of Presidents Washington, Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Lincoln into Black Elk Peak’s granite mountain representing the nation’s birth, growth, development and preservation. Mount Rushmore is located near Keystone and sculpted on the sacred Lakota site “Six Grandfathers,” which the government gave to the Sioux as part of their reservation.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1980 in favor of the Sioux and ordered a reparation payment of $102 million. The tribe refused and only wanted their land back, deeming this usurping a desecration and calling the site the “Shrine of Hypocrisy.” More than 2 million people visit Mount Rushmore each year people around the world recognize it as an American symbol.

Chief Henry Standing Bear commissioned Polish sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski in 1948 to create a similar monument honoring Oglala Lakota Warrior Crazy Horse. This revered figure had fought in the Battle of Little Big Horn and died when a military guard shot him for refusing imprisonment at Camp Robinson. Later the American government honored him on a U.S. postal stamp and some history books include him in the story of Westward Expansion. The Crazy Horse Memorial refuses government funds, and after 76 years is far from completion.

Many Native Americans oppose this project and see it only as another defiling of sacred land and an affront to Crazy Horse himself, who during his lifetime refused to be photographed or his likeness made. Indian activist Russell Means compares this monument to Christians or Jews carving up Mount Zion for profit.

South Dakota offers visitors a panoramic view of history—geological, biological, and human. Nowhere on Earth is the record of existence more completely and vividly revealed. I left humbled and serene in these vast dimensions of time and space, which place the human drama in perspective. Within United States history, too, I realized that Mount Rushmore and the Crazy Horse Memorial are built on dinosaur sites and rock formations billions of years old.

I returned home, too, with more compassion for the foibles, frenzy, and faith of humans who trudge along as strangers on this planet somewhere between animals and angels. This kind of cosmic revelation may not occur with every visit, but South Dakota—widely known as the “Land of Infinite Variety”—illuminates the path from where we mortals came and what may lie ahead for our Earthly home, humankind, and the unfolding American story.

Joseph Newkirk is a local writer, photographer and world traveler who has published many of his adventures in newspapers and literary magazines. He is a board member of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, Quincy Museum, Friends of the Log Cabins, president-elect of the Quincy University Retired Faculty and Staff Association Executive Committee, a master naturalist with the University of Illinois Extension and a long-time member of the Gem City Rock Club. He has traveled to South Dakota several times and revels in the history of this Western Frontier state. His trips there were to explore its vast geology, paleontology and natural wonders. He has published many of his worldwide travel stories in literary magazines and newspapers.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.