Remembering 9/11: Harris Broadcast mobilizes to get New York City back on air

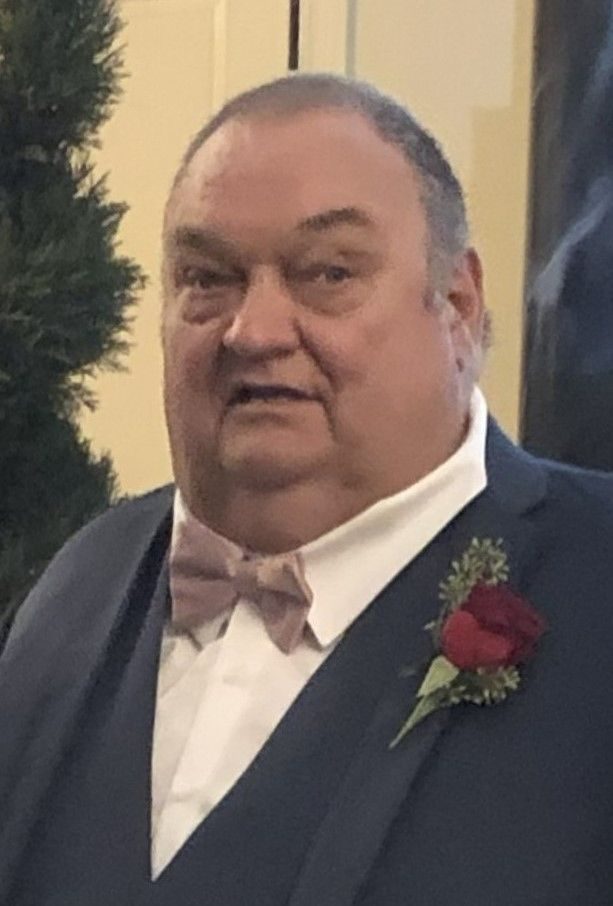

A long-time employee of Harris Corporation’s Broadcast Communications Division (now GatesAir), Don Carpenter was manager of Harris’ TV service department 20 years ago when, at 8:45 a.m. EDT on Tuesday, Sept. 11, an airplane slammed into the World Trade Center’s North Tower.

“I was in shock,” Carpenter recalls. “On a television near my office, I saw the World Trade Center on fire. I remember going back to my office. I could see people standing silently in front of the TV.

“It had started out as a nice September day.”

It wouldn’t stay that way.

Soon after getting to work, Carpenter received a phone call from Rick Scott, Harris’ lead TV field service engineer. He was installing a transmitter near Houston. Listening to the radio as he drove to the installation site, Scott learned a plane had hit the World Trade Center. He rushed to a phone to alert Carpenter.

If ever there was a time when up-to-the-minute news was critical, this was it — but Carpenter recalls New York City radio and television stations being off the air.

“The rest of the world could watch what was happening on TV, but most of New York was dark,” said Dave May, Harris’ director of service at the time.

Sparse Backup

Since the World Trade Center’s first broadcast antenna was installed in 1978, it had become the pre-eminent transmission site for the New York City metropolis. Four radio stations and nine television stations had their transmitters there in 2001, delivering over-the-air broadcasts through antennas on top of the North Tower.

To ensure uninterrupted broadcasting, each station had a backup transmitter, ready to go on air within seconds if the main transmitter failed. Dead air is the bane of every broadcaster’s existence, especially in top markets like New York City.

There was only one problem. Most of the stations on the World Trade Center located their backup transmitter right next to the main transmitter on the 110th floor of the North Tower. After the twin towers crumbled on 9/11—the South Tower at 9:59 a.m. EDT after being struck by a plane at 9:03 a.m., and the North Tower at 10:29 a.m. — only one of the TV stations was left with a backup. WCBS-TV had a 20-year-old Gates-Harris transmitter (albeit in need of a new motor for cooling) 3.7 miles away on top of the Empire State Building.

“Until 9/11, we didn’t think about losing a whole building,” Carpenter said. “Now broadcasters have their transmitters at two locations for the most part.”

Taking Stock

The immediate need was to get New York City stations back on the air, and Harris was the company to do it. Since its founding in Quincy as Gates Radio in 1922 by 14-year-old inventor Parker S. Gates, the company had earned a reputation for unparalleled service and technical innovation. Now, in the wake of an al Qaeda terrorist attack that was not yet understood, it was time to kick in.

“I immediately sat down with Lou Ann Duryea, Harris Broadcast’s market research manager,” Carpenter said. “We made a list of what equipment each station had and what each station would need. Meanwhile, Bob Crockett took inventory of everything we had in manufacturing and everything we would need to respond.”

Within a day, a Harris team that included Quincy plant manager Sue Osier, service and design engineers, sales and manufacturing specialists, and order administrators teleconferenced with broadcasters from the impacted stations.

“I remember sitting at the roundtable in Harris’ Conference Room A and being on a call with all the major networks,” May said. “I thought, ‘This is extraordinary, that after such a catastrophe, competitors are coming together to get New York City back on the air.’”

Plans were made to establish a transmission facility at the abandoned Alpine, N.J., site, where the first FM signal was broadcast in the 1930s. Time was of the essence.

Quick Deployment

“Even before a plan existed, we began deploying field service engineers to the New York area,” Carpenter said. “Since the airlines suspended service, our people rented cars and drove to New York from places as far away as Texas and Florida. Our focus was getting them on-site as quickly as possible.”

While employees at Harris’ Quincy plant worked around the clock to pull together intricate transmission systems, Harris field engineers arrived at the Alpine site.

“The building had been unoccupied for years,” May says. “Four inches of dust was on everything.”

Replacement transmitters arrived in three days. Within the week, the Alpine installations were complete.

“I can’t think of a time when we moved so quickly,” Carpenter says.

Remembering

There was no celebration in Quincy. Only memories remained.

Shortly before 9/11, a Quincy field service team had returned from a lengthy stint at the World Trade Center, installing a new digital transmitter on top of the North Tower.

“It was a close call,” May reflected somberly.

Neither he nor Carpenter (along with many people who worked in the tight-knit broadcast industry on 9/11) can think of that day without remembering the six broadcast engineers who died on the North Tower. Reportedly, one was installing digital equipment on the 104th floor, and five were in the 110th-floor transmitter room. All were focused on only one thing: keeping New York City on the air.

A Monumental Tribute

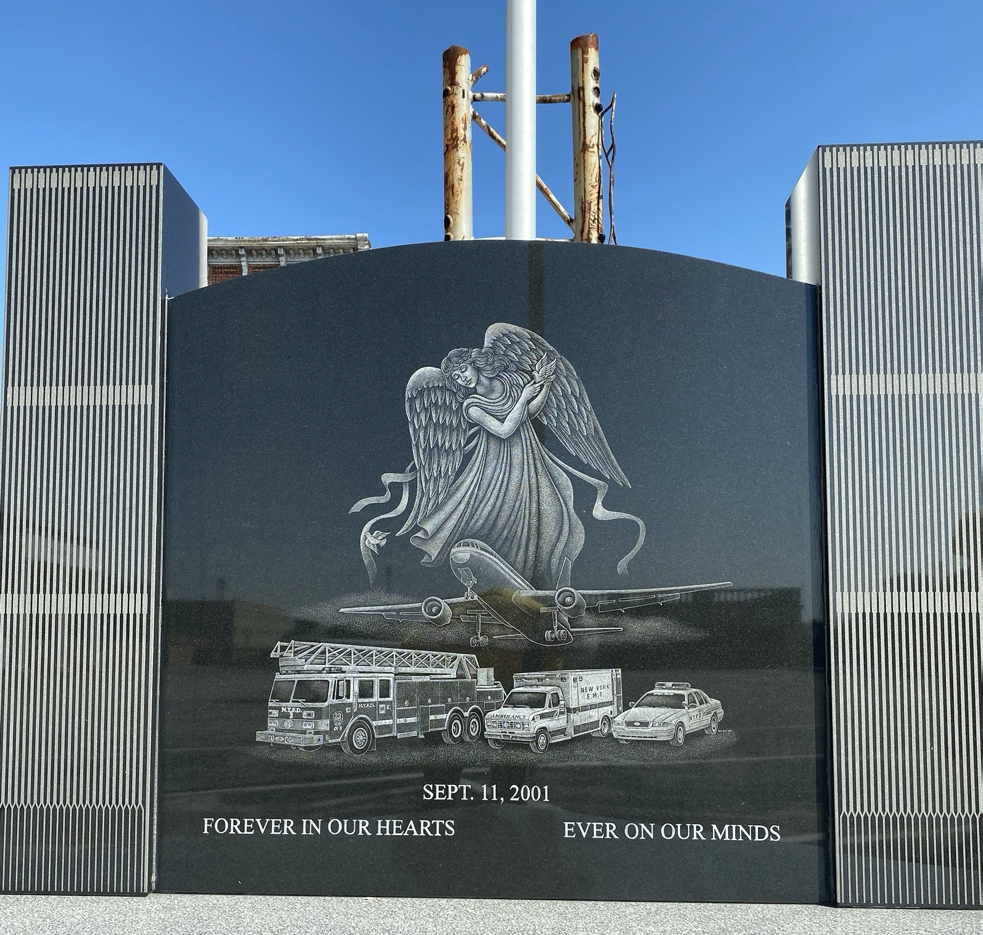

Driving along Quincy’s Maine Street, you may miss an odd-looking, 15-foot-tall structure in the City Hall parking lot between Seventh and Eighth Streets. For residents who worked for Dielectric’s antenna operation in Palmyra and Harris Corporation’s Broadcast Communications Division in Quincy on 9/11, the artifact — now part of the City of Quincy’s 9/11 memorial — has special significance.

Since its dedication by Mayor John Spring 10 years ago, the memorial has served as a reminder of heroic work by area residents to get New York City back on the air.

The charred and twisted 7,000-pound artifact is a remnant of the broadcast tower that held almost all New York City’s television antennas and four FM antennas. Perched on top of the North Tower, it was one of the last identifiable structures to hit the rubble as horrified TV viewers watched the second of the twin towers crumble in a plume of smoke and debris.

For Jeff Steinkamp, Quincy’s city engineer from 2003 to 2013, the artifact is more than evidence of one of our nation’s greatest tragedies. For him and others who supported the memorial, it was a ministry.

“Ministry doesn’t have to be in a church,” he says. “It can also be in a community.”

A Complex Process

Quincy’s first 9/11 memorial, a marble tribute to First Responders, was installed in front of City Hall in 2005. It was the Eagle Scout project of Boy Scout Troop 99’s James Ryan Keller.

Planning by the city to expand the memorial with an artifact from Ground Zero began in 2010, with Steinkamp, Spring, Police Chief Rob Copley, Fire Chief Joe Henning and EMS Chief Paul Davis serving on an artifact committee.

The group quickly found it was not a simple process. Steinkamp was told three times that all “artifact material” was spoken for.

“I just kind of kept at it,” he says.

His break came when he managed to reach Norma Manigan, “the head artifact lady,” by phone.

“She was in the World Trade Center on 9/11 and told me the story of her escape,” Steinkamp said. “When she finished, I said, ‘I have a story, too.'”

Finding C-5

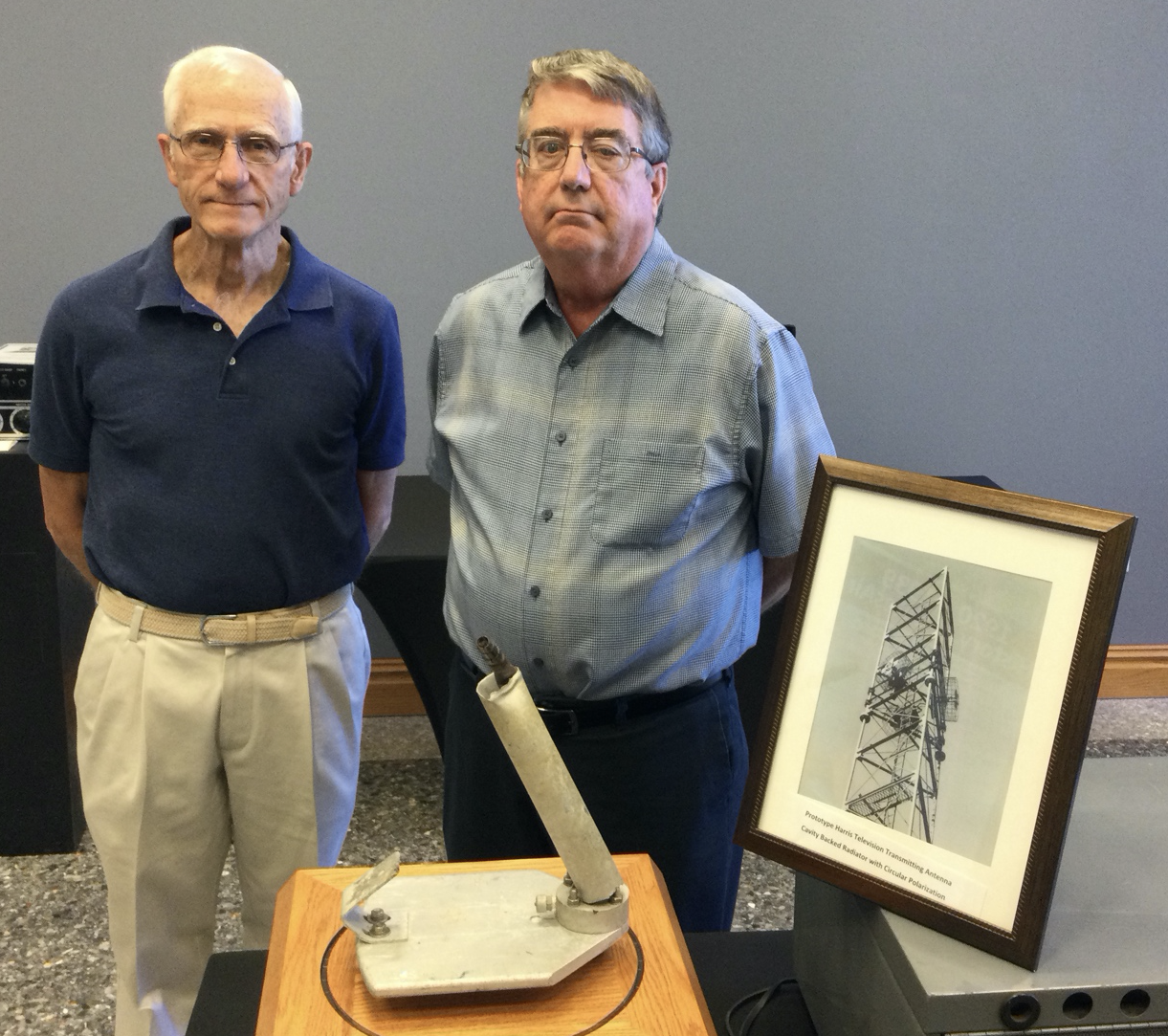

Steinkamp told her that as a young mechanical structural design engineer for Harris, he had been on top of the North Tower for the installation of TV antennas in the late 1970s. He’d also been working for Dielectric, a company that supplied emergency antennas to New York broadcasters, on 9/11. (Harris sold its broadcast antenna business to Dielectric in 2000.)

“When I asked, ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting if we could get remnants for a Quincy memorial?’, Norma replied, ‘We have lots of antenna parts! Nobody’s ever asked for or wanted them,’” Steinkamp said.

The structure that the antennas were mounted on was located, and the City of Quincy applied for the artifact identified simply as “C-5.” Considered as evidence of the 9/11 attack, “C-5” was awarded to Quincy by Court order with conditions attached — among them, to “treat the artifact as if there are human remains on it.” More than 2,700 people died at the World Trade Center that day.

2,000-Mile Pilgrimage

In mid-July 2010, Thompson Trucking sent a semi to New York to pick up “C-5.” Thompson Trucking was among businesses who allowed the memorial to be raised at no cost to the city. (The complete list of donors is on a plaque at the entrance of City Hall.) Steinkamp went along for the 2,000-mile roundtrip, taking vacation time and paying his own way.

He recalls arriving at the 800,000 square foot hangar at JFK Airport where salvaged 9/11 remnants were preserved. After presenting the necessary paperwork and learning there would be a wait, Steinkamp spent an hour walking among the remnants.

“It was humbling,” he says. “I felt patriotic, and I knew I was on holy ground.”

He saw first-hand the unforgettable full devastation of human hatred — crushed fire trucks, squad cars that were smashed to a height of 18 inches, and 48-inch by 48-inch steel beams which, he remembers, “were rolled over like pieces of taffy.”

Upright Again

Another choking moment was to come.

“The memorial was put up a couple of days before the dedication,” Steinkamp remembers. “As it was put in place, I had a thought that for the first time in 10 years, the tower was upright again. We had survived as a country and survived the worst attack on our soil.”

Steinkamp recalls watching visitors to the memorial from his office in City Hall while he was city engineer.

“They would look at it in awe, and then reach out to touch it,” he recalls. “It is so important to remember … to make the connection.”

Steinkamp paused, then reverently added, “For my generation, this was our Pearl Harbor.”

Martha Brune Rapp was senior manager of strategic communication for Harris Corporation’s Broadcast Communications Division on 9/11. Called to ministry in 2005, Rapp received a doctorate in preaching in 2018. She is a certified spiritual director and author. Her first book, “Conversations with Benjamin: A Spirituality of Preaching that Heals,” was published by Wipf and Stock of Eugene, Ore., earlier this year.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.