If the Department of Education is abolished, what could that mean for local school districts?

QUINCY — Donald Trump laid out a new vision for education in America in a September 2023 campaign video that included closing the U.S. Department of Education (ED).

“We’re going to end education coming out of Washington, D.C.,” he said.

Sources close to President Trump shared last month that the administration was working on an executive order to do just that. Additionally, he said he wants his pick for Secretary of Education, Linda McMahon, to “put herself out of a job.”

McMahon, the former CEO of World Wrestling Entertainment and head of the Small Business Administration who served for one year on the Connecticut Board of Education, affirmed her support for the president’s plans during her confirmation hearing in February. She said she “wholeheartedly supports and agrees with (President Trump’s) mission” to “return education to the states.” She was officially confirmed by the Senate on March 3.

McMahon’s confirmation came hours before the deadline for ED staffers to voluntarily resign from their positions in exchange for a $25,000 cash payout, as offered in an email sent to eligible staffers Feb. 28.

Muddy River News reached out to superintendents in the area to get a better understanding of how the dismantling of the ED could affect families in West Central Illinois and Northeast Missouri — and the millions of dollars in federal education funding they’ve come to rely on.

Local districts received more than $30 million in federal funding for 2024-25

“Nobody really knows what’s going to happen, but it is a substantial amount of money that would really affect a lot of our students, especially our at-risk students,” said Ritchie Kracht, the longtime superintendent of Clark County R-1 Schools who was recently appointed to run the Hannibal School District.

Hannibal schools receive about 9% of their funding from federal sources, which translates to about $1,350 per student. The district budgeted roughly $4.48 million in federal revenue for the 2024-25 school year, including roughly $17,000 in student enrichment grants, $990,000 in grants for the disadvantaged and $1.1 million in funds for students with disabilities.

“It would be devastating to lose all that money,” Kracht said.

Todd Fox, interim superintendent for the Pikeland School District, said funding concerns are “pretty cyclical.” He’s faced difficult budget constraints before, which is why he said he isn’t worried yet, but he is concerned.

“A lot of very important programs that affect the most vulnerable populations of our schools could be affected by a decrease in funding,” Fox said.

Pikeland’s federal funding for this school year was a little less than half of Hannibal’s — around $2 million, including $306,000 in grants for the disadvantaged and more than $20,000 in student enrichment grants. A quarter of it ($513,000) has been allocated for special education programs.

The Quincy Public School District’s budget dwarfs that of surrounding districts, as does its federal funding. The district estimated it would receive more than $26 million this year, including $2.2 million in grants for the disadvantaged, $266,000 in student enrichment grants and $2.5 million for special education.

Todd Pettit, superintendent of Quincy Public Schools, said in an email that he did not want to make a statement for this story since “no direct actions that impact the district” have been made at this time.

Sources close to the Trump administration announced last month that the White House was drafting an executive order to close the ED, despite not having the authority to do so. Congressional approval is required to close a federal agency in the same way it’s required to create one.

The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) did not require congressional approval for its creation because it is not a federal agency. Because of this, DOGE falls into a grey area in terms of ethics laws and financial disclosures that apply to all federal agencies and employees, which has caused concern among lawmakers in the wake of widespread funding cuts by the department — especially since DOGE was established to update the government’s computer software.

The ED is currently listed on DOGE’s website as garnering the second-highest savings in comparison to savings yielded by cuts made to various other departments. Atop the list of terminated grants on DOGE’s “Wall of Receipts” — which was found to have multiple errors that inflated the amount of “savings” by double — are 22 education grants totaling $138.9 million. DOGE’s website does not provide details as to what the grant money was for.

DOGE is headed by Elon Musk, the richest man in the world. His companies have received at least $38 billion in government contracts, loans, subsidies, and tax credits since 2003, including $6.3 billion last year alone. Musk is the owner of several companies, including SpaceX, Tesla and X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter that is estimated to be worth roughly 70 percent less than it was when Musk bought it in 2022. None of Musk’s companies are listed on DOGE’s “Wall of Receipts.”

What does the ED do?

The ED doesn’t set curricula for any academic level, nor does it determine enrollment or graduation requirements. It also doesn’t provide the majority of educational funding for schools.

Rather, the ED was established to provide supplemental financial and administrative support to the states, to collect data and conduct research, to issue regulations on how money can and can’t be spent and what policies must be in place at funding-eligible institutions, and to ensure equal access to educational opportunities for all children, regardless of race, sex, religion, ethnicity, income level or able-bodied status.

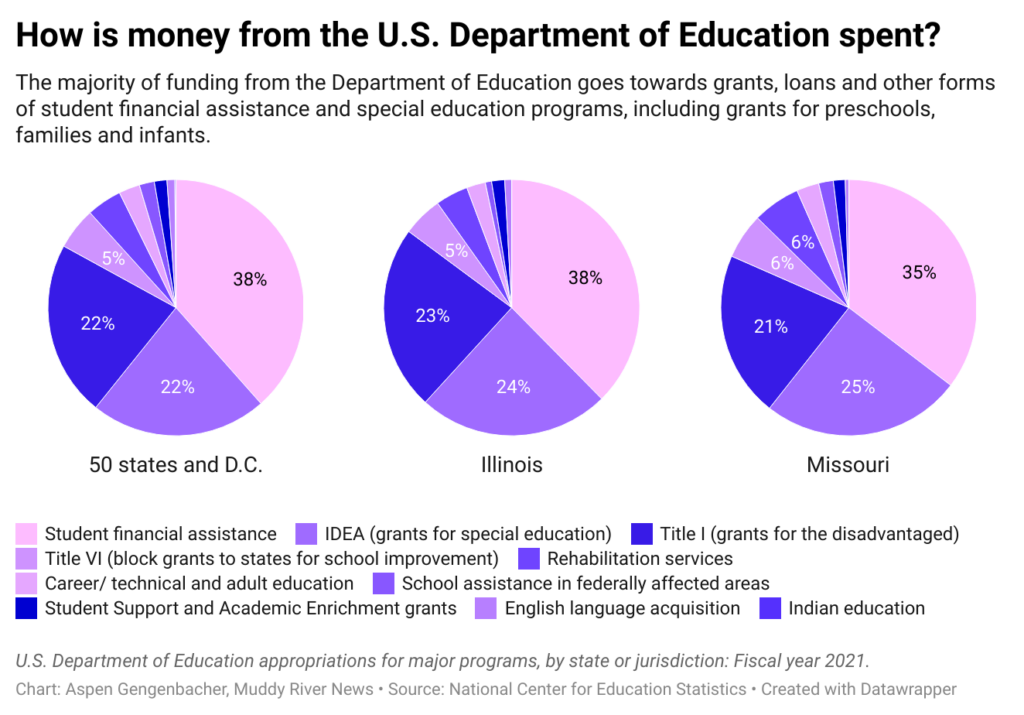

The overwhelming majority of funding managed by the ED is administered in the form of tuition assistance at postsecondary institutions, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) grants and Title I grants, which serve low-income students.

“We hire a lot of teachers — Title teachers, special education teachers — based on that money,” Kracht said. “How would we continue to pay for those staff members?”

Schools also receive a significant amount of federal dollars for various education-related programs that are not administered by the ED, such as the Head Start Early Childhood program administered by the Department of Health and Human Services and the Free and Reduced School Lunch and Breakfast programs administered by the Department of Agriculture.

What could happen if the ED is dissolved?

The federal government’s contributions to tuition assistance skyrocketed after the 2008 recession, and its contributions to education across the board increased significantly as a result of the pandemic. Many states are not prepared — financially nor administratively — to incur the additional costs if the funding falls through.

The number 435,000 is significant in Fox’s memory. He said it was the amount of dollars the state owed to the Southeastern School District in Augusta — where Fox previously worked as a teacher, coach and superintendent throughout a 33-year career — following the 2008 recession.

“This is kind of a double whammy in regards to — what is the federal government going to end up doing? What’s it look like? Then also with the state budget crunch that we are experiencing and going to experience, it will be a very interesting spring in Springfield,” Fox said.

Following years of balanced budgets, recent upticks in health care and pension costs have contributed to a $3.2 billion deficit in the Illinois budget for 2026. The uncertainty of guaranteed federal funds — for education and other sectors — combined with the end of pandemic-relief funds has led to grim projections for the years ahead.

“None of us — whether it’s Hannibal, Clark County, Palmyra, Quincy — none of us have that money to replace the money we get from the federal government. If that federal money is not there, it’s going to be devastating to all students in all school districts in the Tri-State area,” Kracht said.

Legislation has already been introduced in Congress to end the ED. One bill, introduced by Rep. Thomas Massie of Kentucky at the end of January, is plainly written as “The Department of Education shall terminate on December 31, 2026.” It has garnered the support of more than 30 Republican co-sponsors, including Rep. Mary Miller of Illinois and Rep. Eric Burlison of Missouri.

“All schools take care of their kids,” Fox said. “There’s no question that we might have to dip into some of our reserve funds, but that’s what we’ll do to take care of our kids.”

Dipping into reserve funds, cutting non-mandated programs and increasing local property taxes are all possible pathways for making up some of the funding that could be lost.

It’s also possible that the funding wouldn’t be lost at all, but rather outsourced to another federal agency.

Another bill, introduced by Rep. David Rouzer of North Carolina on Jan. 13, goes into much more detail about what would happen following the ED’s elimination, outlining which programs would be exempt from federal funding cuts and which agencies they’d move to. IDEA funds, for example, would be moved to the Department of Health and Human Services, and the federal Pell Grant program would be managed by the Department of the Treasury.

The bill notes that the departments that would house the programs would only assume administrative responsibility. It is unclear if the departments would receive additional funding to hire the personnel and establish the infrastructure needed to manage the extra workload.

A reshuffling of ED funding and administrative responsibility is unlikely to be the end of the president’s crusade against the education system in its current form.

Project 2025 — a document of policy proposals authored by several staffers from Trump’s first and now second term — proposes Title I funding (federal funding allocated to grants for low-income students) first be switched to tuition vouchers for families to send their children to private schools of their choice — which often do not have to comply with the same civil rights laws and transparency measures regarding academic performance — before being entirely phased out after 10 years.

It also proposes that money currently being administered via IDEA grants for students with disabilities be given directly to parents.

What is President Trump’s vision for education?

“The U.S. spends more on education than any other country in the world, and yet we get the worst outcomes. We’re at the bottom of every list,” Trump said in a 2023 campaign video.

Is he right?

Sort of.

The U.S. spends a lot on education, ranking fifth out of 38 OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries in per-pupil spending for K-12 funding and second per-pupil in postsecondary education. However, the U.S. ranks 40th of 197 countries in education expenditures as a percentage of gross domestic product.

As far as academic performance, of 81 countries participating in the PISA (Program for International Student Assessment), American students ranked 26th in math, 10th in science and 6th in reading — each category indicating an improvement from pre-pandemic scores in 2018.

“I think in rural America out here — Northeast Missouri, Western Illinois, Southeast Iowa — in our area right here, we are doing an incredible job with our students. We’ve got a bunch of teachers who care about kids that work hard every day,” Kracht said. “We are doing a good job in our classrooms.”

Abolishing K-12 teacher tenure, “drastically” cutting the “bloated” number of school administrators and rewarding “teachers who embrace patriotic values” with “merit pay” were outlined as education policy proposals in a July 2024 Trump campaign email.

The president signed an executive order in January to end “radical indoctrination in K-12 schooling,” which stated that all “recipients” of federal dollars must be in compliance with his executive order pertaining to diversity, equity and inclusion. It also ordered the re-establishment and funding of the 1776 Commission, which aims to promote “patriotic education” — “a presentation of the history of America” that is “ennobling,” “beneficial and justified” and “proper.”

The 1776 Commission has also been tasked with broadcasting “bi-weekly lectures” on “patriotic education” to the country throughout 2026.

“We will teach students to love their country,” Trump said in the video.

The subjective language of Trump’s proposals and executive orders makes it unclear if instruction on certain parts of America’s very real history will be included in such education, such as:

- slavery (1619-1865)

- the Mai Lai massacre (1969)

- the murder of Emmett Till (1955)

- the Trail of Tears (1830-1850)

- the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire (1911)

- segregation (late 1800s-late 1960s)

- and the Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee (1932-1972).

“As far as history, I don’t know if there’s ever been any mandates on what we can teach. I mean, history is history. It’s what happened, you know? I do not recall having it at any time where we were told what we could or could not teach about history. You know, maybe in health, there’s been some things they wanted us to teach or not teach, but not history class,” Kracht said.

Trump also stated in the video that “we will support bringing back prayer to our schools.” It is unclear if this sentiment, currently barred by the Constitution under the First Amendment, extends to non-Christian religions.

What now?

“One of the things that we’re not going to do is we’re not going to overreact and start cutting services or start laying off teachers. That’s not where we’re at right now. That would make no sense until the dust settles and we see how this all plays out,” Fox said.

Any legislation to end a federal agency would require 60 votes to overcome a filibuster in the Senate. Republicans control both chambers of the House, but barely. It’s highly unlikely the efforts would result in congressional approval to dissolve the agency.

But while it’s against the Constitution for a president to unilaterally dismantle an agency, it’s much less clear what the boundaries are for a president chipping away at an agency’s functionality bit by bit.

“We’ve got a political football game going on right now that schools are in the middle of, unfortunately,” Kracht said. “Depending on what decisions are made, kids could suffer and not get the services that they both need and deserve.”

“That will be very disheartening if that happens.”

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.