The St. Francis School Fire of 1899: Gripping Disaster

(This is the fourth of six stories about the St. Francis School fire in December 1899, when 12 girls burned to death in one of saddest chapters of the Quincy community’s history.)

Read Part 1: Prosperous Quincy of 1899

Read Part 2: Christmas is Coming to Quincy

All that was left was for the community to confront the gripping disaster. The town was only now beginning to get an inkling of the immensity of the tragedy.

People had paid little attention when they heard the first clang of the fire engines. Fires were so common, with kerosene heaters and lamps. At Christmas it was all the worse, when people decorated trees in the German tradition with lighted candles. But when the children began to return home, word soon spread quickly that the fire was at St. Francis School and there was a mass exodus of mothers from their homes. They dropped everything and ran, many of them without coats or hats or gloves despite the cold, toward the school.

When they got there, a line of policemen barred the front doors. The women tried to push past the policemen.

“Where’s my child? Please let me in,” they pleaded. “Who are the children inside?,” they begged to know.

But no one could or would answer these questions. It was only later that it was learned that 12 young girls lost their lives.

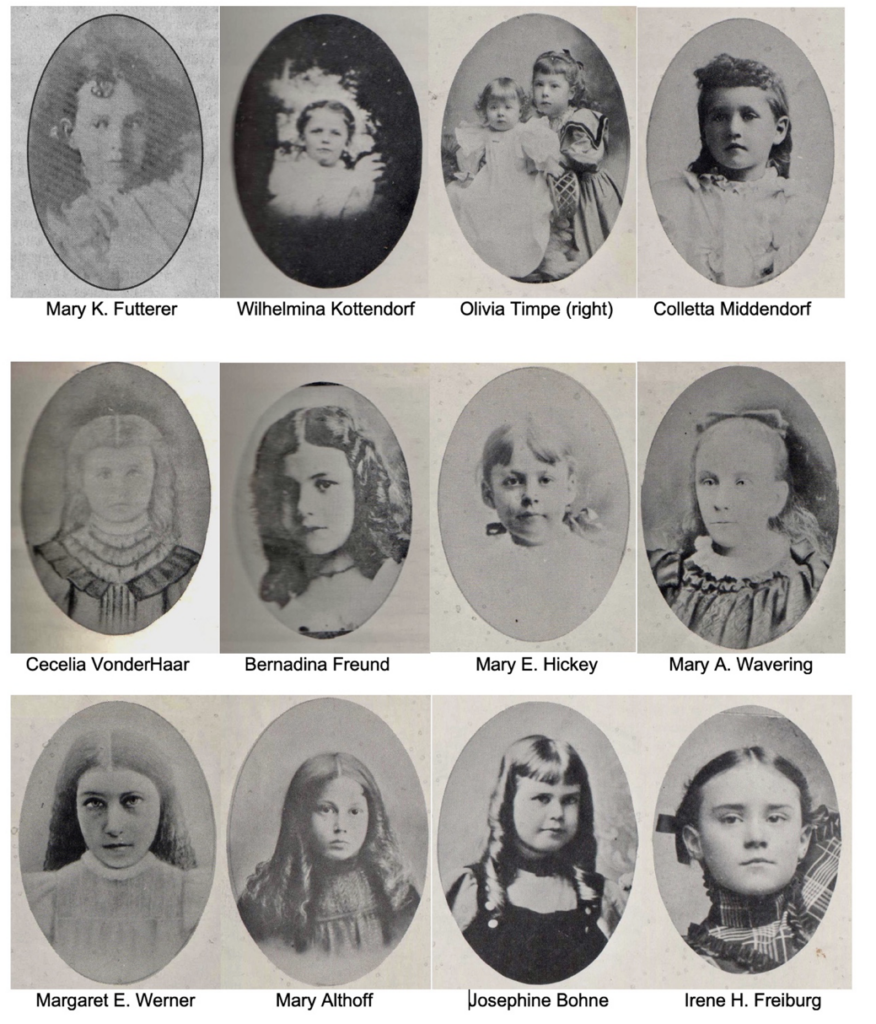

Images Compiled from and Courtesy of the Quincy Public Library: Quincy Area Historic Photo Collection

Three of the four girls who died immediately were burned beyond recognition. The six who still lived were injured beyond giving their names. Sister Theotima was the only teacher with the list of children participating in the program and she was burned so badly that the doctors would let no one talk to her. There was nothing to do but wait. News reports remained incomplete as to the extent of the tragedy.

The Quincy Daily Journal of December 22, 1899. Image from the Quincy Public Library’s Historical Newspaper Archive

The frantic crowd grew larger with every minute that passed. And to make matters even worse, many of the children who escaped safely from the building did not go home right away, but stayed near the school. A long list of missing children was compiled. On that list were the names Lillian and Clara Koesyan, and their mother was among those standing in the crowd.

Soon word of the horror reached the fathers in their workplaces and they, too, rushed to the scene. They came from the Freiburg Boot and Shoe Company, from the flour mill, from the iron company, and the plow company. Joseph Kottendorf raced over to the school from the Chanson-Emery foundry. George Bohne closed his blacksmith shop on North 12th Street.

William Middendorf ran over to the school from his lumber yard in search of his missing daughter Coletta and was persistent enough to gain entry. He says in a letter written four days later to his brother – and here the personal record differs from what was printed in the newspapers – “I found Coletta dying in the corridor, in front of the hall, together with three other girls already dead. But not being able to identify her with certainty, I ran downstairs, asking for Coletta. Ed Hermeling, a neighbor’s boy, told me that Coletta went home with her sister. Home I sped, but Coletta was not at home. Fully realizing now that Coletta was the dying girl in school, I hastened back with [her sisters, ] Clara and Lizzie, who seeing shoes and stockings and hairband, exclaimed, “This is Coletta.” Coletta’s feet were always cold and she would wear two pairs of socks, something her sisters knew but their father didn’t know. The newspaper said that the moments following this sad identification were so heartrending that the firemen turned away. It is heartrending to imagine this scene even these many years later.

One floor below, doctors were now with the little girls. When the call went out, 42 of the town’s 92 doctors rushed to the school as fast as their horses could run. They jumped out of their buggies without bothering to tie the horses, but other men quickly took over that task. It was something they could do when there was really nothing they could do. Inside, the doctors felt just as helpless. They put on the lotions and tried to ease the pain. Then they accompanied the children to St. Mary’s Hospital in ambulances that arrived shortly.

But frantic parents continued to arrive at the school long after the children were taken over to the hospital.

Bernadina Freund’s father, Joseph, was at his home on 13th Street when he heard the news. He jumped on a horse without bothering to put on a saddle or bridle, and dashed up Vine Street on a wild search for his daughter. They told him his daughter had been taken to the hospital. He remounted his horse and dashed off to the hospital. There he found her dying.

Anton Wavering came as soon as he heard the news over at the flour mill. He arrived at the school, terrified that his daughter Mary might be among the dead.

One of the firemen asked, “Had she any particular clothing by which the body could be identified?”

“Yes,” answered the father, “She was wearing a gold ring.”

Then the fireman replied with tears in his eyes, “One of the dead girls was wearing a gold ring.” Mr. Wavering rushed off to the morgue, where he identified Mary by her gold ring.

Parents searching for missing children rushed to the hospital, and rushed through the halls looking for them, but by the time they arrived, the children’s faces had been covered with cotton bandages, and identification was next to impossible. So mothers and fathers went from one cot to the next, whispering their child’s name, praying for no response. When a feeble response of recognition came back, mother and father would break down completely.

The sisters were there to offer the heart-broken parents what little comfort there was, although there simply were no words. The doctors worked, with coats off and sleeves rolled up, to ease the children’s pain. It was also their sad duty to inform the parents, desperate for some small ray of hope, that there was none.

The parish priests administered the last rites and one by one, during the evening, the little lives went out like candle flames. At 7:00 o’clock, Bernadina Freund and Mary Futterer died. Josephine Bohne died at 7:15. Wilhelmina Kottendorf died at 7:30. Olivia Timpe died at 8:00 o’clock. Margaret Werner died at 9:30. At 10 o’clock, the last body was carried out and taken the five blocks to Freiburg’s Funeral Home.

Across town, in her home, Mary Hickey died at 7:30. And Cecelia VonderHaar died at home at 5:00 the next morning.

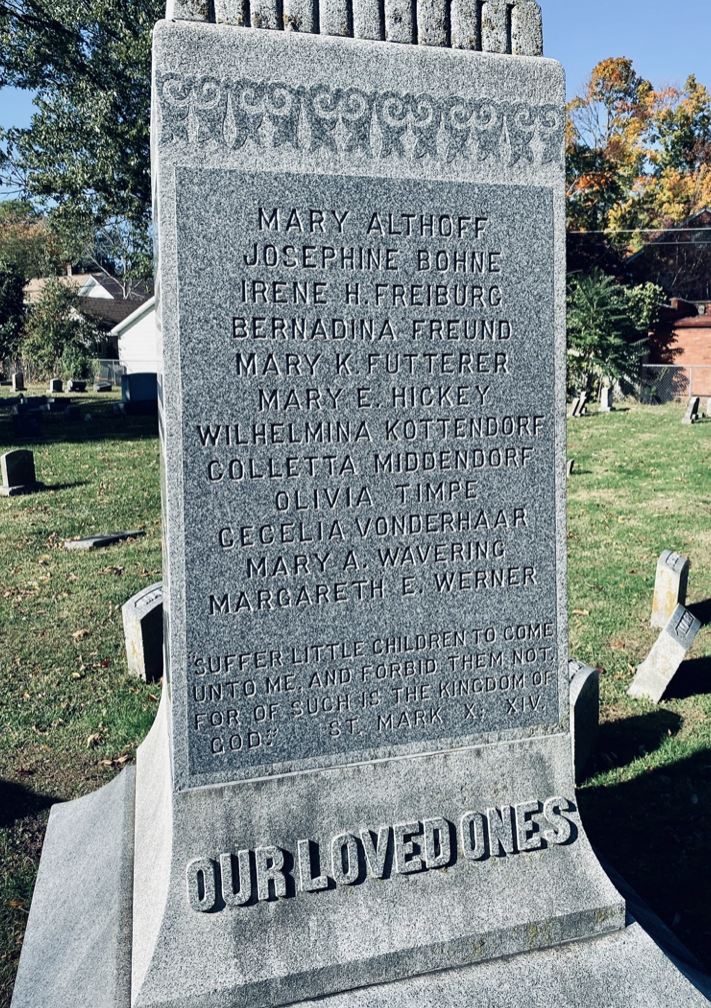

The death toll was 12 little girls – “Our Loved Ones” as would eventually appear on a memorial to remember them.

St. Francis Fire Memorial Lists “Our Loved Ones”. Image by James A. Rapp

Shortly before dinnertime, when Lillian and Clara heard their mother come into the house, when they heard her weeping, they climbed out of their hiding place. When their mother saw them alive and safe, she did not spank them. She embraced them with tears of joy which other parents were denied.

Helena Soebbing survived, thanks to the quick thinking of her sister Clara. Laura Menke, Lulu Bauman, and Elenora Timpe also survived, but were terribly burned.

So were the teachers who fought so heroically to extinguish the flames and save the children. Father Andrew, Professor Musholt, and the Reverend Nicholis Leonard, who was rector of St. Francis College, were badly burned on the hands, as was Gerhard Koetters, the janitor of the school, and Sisters Ludwiga, Radulpha, and Ephia.

But Sister Theotima suffered the worst bums, on her face and hands and arms as she struggled to save the girls.

They were all taken to St. Aloysus Orphan Asylum and attended to by Dr. Koch and Dr. Bieme. And while their own bums were being dressed – through their own terrible suffering – Father Andrew and the sisters asked constantly about their children. But the news was so terrible that the doctors would not allow them to be told. There would be time to mourn.

Carolyn Rapp is a writer, storyteller, book lover, traveler, and mother of three grown children. She lives with her husband, Michael Rapp, in McLean, Virginia. She also is the author of Garden Voices: Stories of Women & Their Gardens, published by Water Dance Press.

By and copyright © Carolyn Freas Rapp

Thanks to the Quincy Public Library for allowing use of images from the Quincy Area Historic Photo Collection.

Muddy River News is community journalism. Our Home. Our News. Storytelling is an important part of this. We welcome contributors to share stories and material of interest to the community. Email: news@muddyrivernews.com.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.