The serendipitous arrival of Quincy Park Board President Mark Philpot

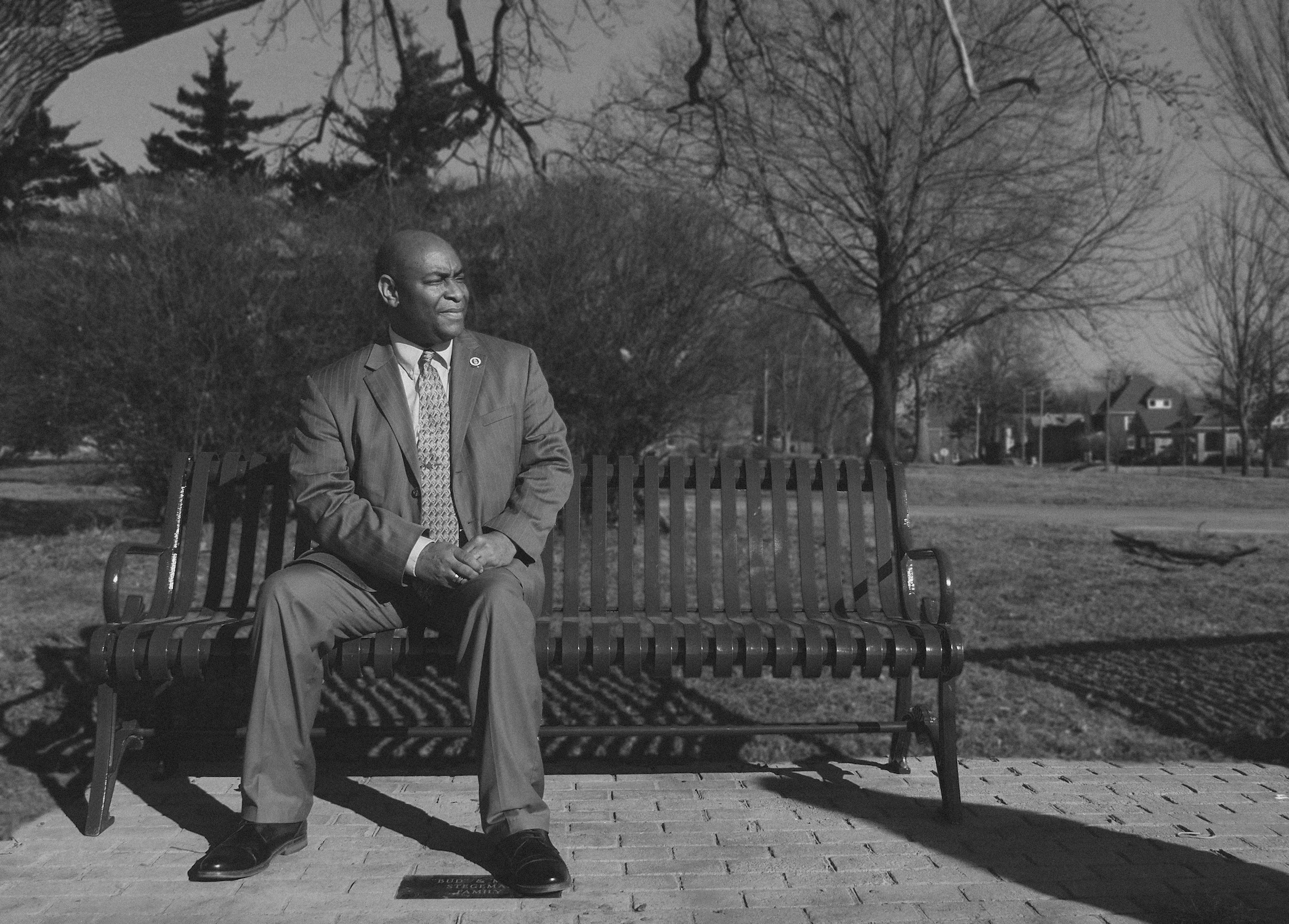

QUINCY — Mark Philpot believes he has one of the best jobs ever. He’s the first Black president of the Quincy Park Board, the “Disneyland of city government,” as he calls it.

His journey here was nearly as magical, too, despite a rough start. He drove 137 miles from the rural town of Wellman, Iowa to Quincy, a town he’d never been to before, in 2017 — all for a really bad blind date.

“Date was going horrible, so I did what I normally do when I’m down and depressed: I went to go sing some karaoke,” Philpot said.

Then a song came on — “Hopelessly Devoted to You,” the tender and melancholic ballad sung by Olivia Newton-John that was made famous in the 1978 movie “Grease.” The heavens opened up to grace the karaoke bar stage for a performance by a woman so spellbinding that not only did Philpot make that 137-mile journey countless times after that, but he made it so many times that he drove his Ford Explorer into the ground — just as it squeaked “Quincy, Quincy, Quincy” over each and every bump of the Bayview Bridge.

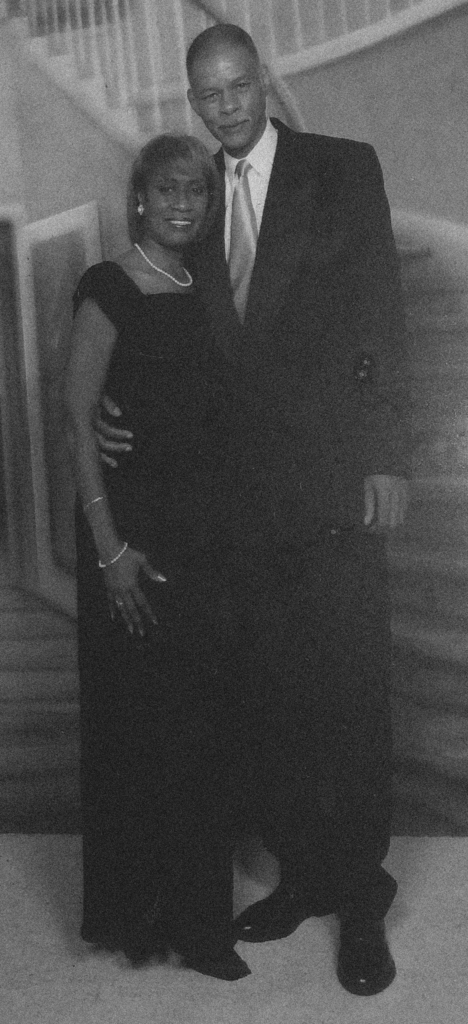

After years of weekend visits to see the woman behind the “angelic voice” whom he now calls his fiancée, Philpot officially moved to Quincy in 2020.

The ‘new school’ of the Quincy Park Board, est. 2023

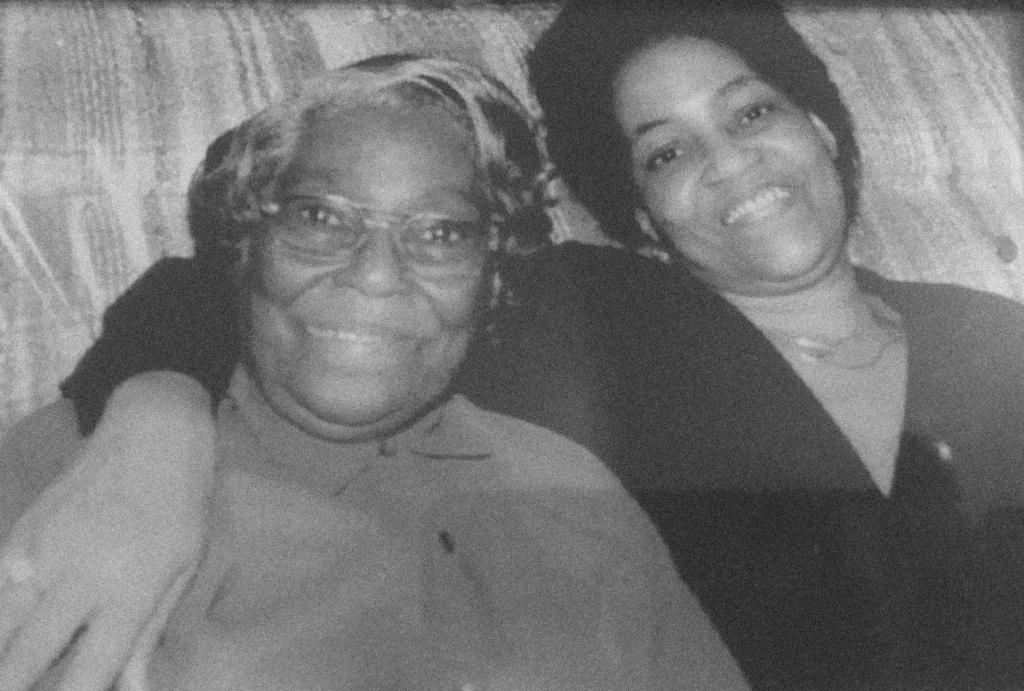

Before Ben Bumbry became the first Black man elected to the Quincy City Council in 2004 and the namesake of Riverview Park following his death in 2018, he was the first Black commissioner elected to the Quincy Park Board in 1993. He served on the board until 2003.

Alan Hickman became the board’s second Black commissioner in January 2023, and Philpot became the third a few months later — roughly 20 years after Bumbry’s departure. Philpot was elected as Park Board president in May 2024.

“I think it’s wonderful, and it should’ve happened a long time ago,” said Bumbry’s widow, Helen Bumbry.

Helen said that by seeing people of color rise to leadership positions in the community, children are motivated to stay in school and continue on to college because they see what’s possible for their own futures.

“I think that it is important to have all populations, but especially underrepresented populations, at the table,” Philpot said. “I’m very adamant about the fact that all voices are important. More hands make the work light.”

Jarid Jones also joined the board in 2023, joining Philpot and Hickman to usher in a new generation of influence on the board.

“It was ‘new school’ as opposed to ‘old school.’ And I don’t think that it was abrasive necessarily, but there was definitely an atmosphere of, kind of, ‘Know your place,’” Philpot said. “When the transition came with the new leadership, that gave us an opportunity to kind of adjust the narrative and to show that we were going to be a board of inclusivity, that we were going to reach out to everyone. We were going to be connected with all sections of the community.”

Rome Frericks has worked with six presidents since becoming the Quincy Park District’s executive director in 2014. He said Philpot’s honesty and ability to be straightforward are among his most notable characteristics.

“(Philpot is) taking the reins but letting us do our jobs and working together to make the Quincy Park District a better place than what it was in the past,” Frericks said.

Before moving to Quincy, Philpot was the first Black alderman elected to the City Council of Wellman, a town with a population around 1,500 where he lived for 11 years before moving to Quincy.

Philpot hasn’t ruled out a future bid for Quincy City Council and is “prepared” to take on a new role if and when the time comes, but he wants to learn more about the community first. Plus, he likes the current representatives for his ward on the council, Jeff Bergman (R-2) and Dave Bauer (D-2).

“You gotta know the landscape, right? And you also gotta recognize your elders, too. People who have been here and have been established, it’s important to gain their trust but also let them see your work,” Philpot explained.

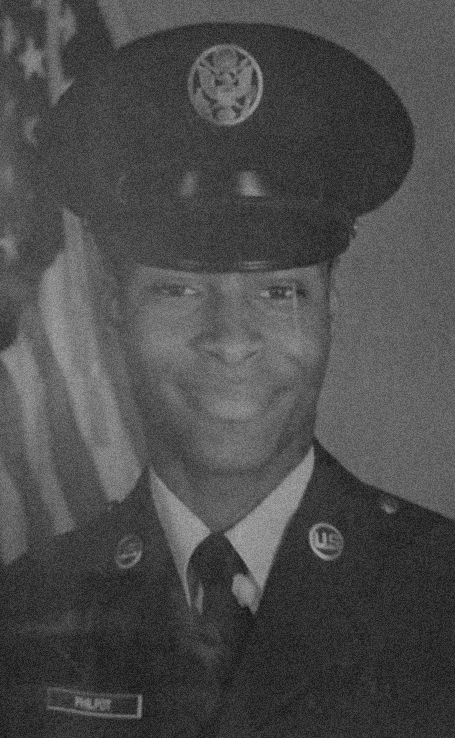

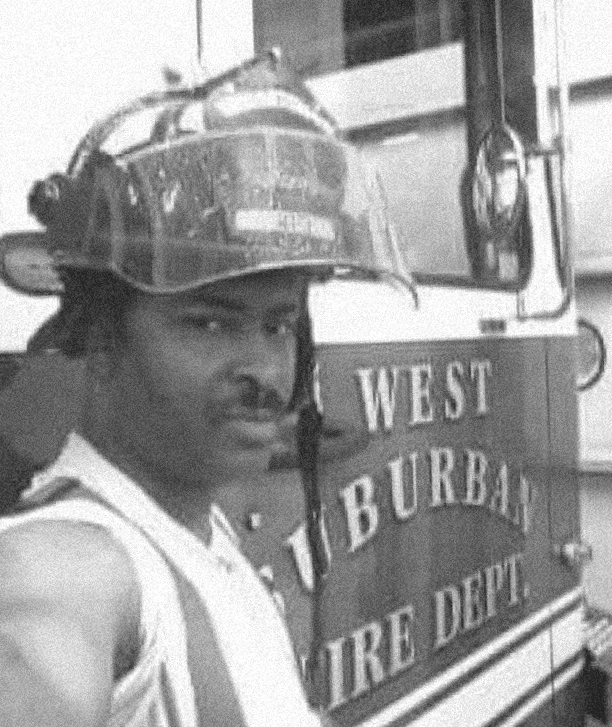

Philpot’s resume features one public service position after another, each having made significant contributions to the skillset he utilizes in a variety of roles today — from serving in the United States Air Force, the Illinois National Guard and the Air Force Reserve to serving as a firefighter, a suicide hotline crisis interventionist and seasonally as a ranger with the Chicago Park District.

He also worked for the Chicago Public Housing Authority for the Department of Public Safety, a job he described as the “protection of the residents of the projects of Chicago.” Daily interactions with people involved in gang activity and substance abuse made it a dangerous position.

“I buried three of my coworkers on that job,” Philpot said.

But for as dangerous and heartbreaking as it was, the role taught him several lessons in being human.

“It taught you a lot about people,” Philpot said. “It taught you not to judge people by their address. It taught you that flowers can grow in concrete, because even though I saw people on a daily (basis) that didn’t know whether they were going to have food to eat that night (or) whether they were going to have clothes to put on their back, they were smart. They were gifted. They had talents.”

Outside of the Park Board, Philpot is on the Community Building Council for the United Way, Together with Tri-State Veterans, American Legion Post 37, the Adams County Democrats and the city’s Human Rights Commission, which he chairs — and that’s just the stuff he does in his free time.

He started picking up shifts in the adult psychiatric unit at Blessing Behavioral Health Center while visiting Quincy on the weekends. He eventually moved to the child psychiatric unit, where he remains on call. He recently started as a client advocate with the Adams County Public Defender’s Office, which involves connecting formerly incarcerated people with the resources they need, such as mental health counseling or getting a driver’s license, to rejoin the community and become productive members of society.

“I want to be of service to others. People need someone to have their back, to actually care that things are good for them tomorrow,” Philpot said.

The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

Philpot’s mother was the deputy director for the Midwest region of the Office for Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, described by Philpot as a punitive role that dealt with instances of corporate discrimination. His adoptive father was the Cook County area administrator for the Department of Children and Family Services, overseeing all of the agency’s officers and investigators in the county.

“(My family and I) very much were involved in being of service to others and doing those emotionally hard jobs that another person might not be able to do but for the goal of making the world or our community a better place,” Philpot said. “That was instilled to me very early.”

‘We shared and we took care of each other’

Philpot’s family history, like that of many Black Midwesterners, is woven into the Great Migration, the decades-long period when roughly six million African Americans relocated to the North from the South, settling in Chicago, New York, St. Louis, Detroit and a handful of other cities in the Midwest and Northeastern regions of the country.

His family’s Great Migration began in Mississippi and flowed into the Chicagoland area, where Philpot was born in 1969.

“It was a different time,” Philpot said. “It was about looking out for your neighbors, and that if you had little, and maybe your neighbor had a little, then together we might have a lot. We shared and we took care of each other, and there was a sense of community and accountability.”

His grandmother, the oldest daughter of Mississippi sharecroppers whose toughness earned her the nickname of “The General,” often used a handful of phrases to put him in his place:

- Don’t be a liar.

- You think you know everything, and you don’t know nothing.

- I knew you before you knew yourself.

- Don’t be trifling.

- I don’t want to miss the time you’re gone.

“I thought this was the meanest old lady in the world. She was teaching life lessons. I didn’t even pay attention,” Philpot said. “I didn’t even understand it.”

A commitment to education, viewed as “the gateway to opportunities,” and the development of a solid work ethic were of the utmost importance in Philpot’s youth.

“We grew up in public housing in Chicago, but they were very serious about the fact that your address does not define you,” Philpot said. “My uncle graduated from Loyola, my aunt went to Southern (Illinois University) at Carbondale and my mom has a doctorate in industrial psychology from Roosevelt, so your address does not define you.”

Philpot played baseball and witnessed the dawn of hip hop in Chicago. He was in the chess club, dreamed of being a meteorologist and had a peculiar obsession with the stock market that led him to watch the numbers “from opening bail to closing bail” during summer vacation.

He graduated from Saint Willibrord Catholic High School in 1987 — the last class to graduate before the school consolidated with another. (The school eventually joined a list of other predominantly Black Catholic schools in the area to close.) He joined the Air Force immediately following graduation and served into the mid-90s.

Philpot’s biological father was in the military, too — Marine Corps. For 18 months in Vietnam, he “sat and sweltered” as a prisoner of war, resulting in a trauma that was so calamitous that it catalyzed a decades-long period of struggles with alcoholism, substance abuse and familial estrangement.

During that time, Philpot’s adoptive father met and married his mother. He took Philpot in as his own, serving as his primary father figure and even endowing him with the last name Philpot.

When he was in his 30s, Philpot reconnected with his biological father. He’s still alive and doing much better now that he’s involved with church and “has had an opportunity to get things together.”

“He’s a success story now, right? He’s visited Quincy, actually,” Philpot said. “He found that coming to Quincy was probably the most peace he’s been able to achieve in a long time.”

Philpot has a “great relationship” with his biological father today. Despite Marvin’s Oct. 2024 death, his influence continues to play a pivotal role in shaping Philpot’s reverence for the public service sector.

“One man gave me life, and one man helped guide me through manhood, and I’m equally indebted to both of them,” Philpot said.

Philpot issues sharp rebuke of ‘cutesy Christians’

Philpot sees the same struggles his biological father once had when looking at the local homeless population.

“We have a problem in Quincy with lack of housing. We have a problem in Quincy with homelessness,” he explained.

Last month, the YWCA conducted its latest point-in-time count — an annual “count of sheltered and unsheltered people experiencing homelessness on a single night in January,” as defined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. During an evening when temperatures dropped to 6 degrees, YWCA employees came across 35 people “walking the streets” with nowhere to go.

“For a town that purports to be so religious, you cannot turn a blind eye to the things that are going on that are a cancer to our community. You can’t have it both ways. You can’t be a cutesy Christian,’” Philpot said. “Because if you really believe in whatever higher power that is — for me, it’s Christianity — if you really believe in that, then you;’ve got to follow all the rules, not just the ones that make you feel really good on Sunday.”

He takes issue with those in the community who claim to be “holy” while passing by a homeless person on the street with “no regard” for what that person might have gone through. They could be veterans plagued by the same trials and tribulations of his father.

“You can’t turn a blind eye, you can’t wish them away, can’t ship them to Hannibal, you can’t do any of those,” he said.

“Yeah, I said that.”

Philpot isn’t afraid to speak his mind, no matter the audience.

“I recognize where I am and the landscape in which I operate. I make no qualms about the fact that I’m a registered Democrat and I’m vice chair of the party for the county,” he said.

Philpot deemed his approach to politics as “middle of the road,” finding he tends to meet people where they’re at to find common ground more often than not. Most people share in the same hardships, the same daily responsibilities to their families and their community and the same desire to improve the quality of life for their children, regardless of the party they identify with.

He believes a person’s motivation for seeking office matters more than the letter behind their name. He questioned if the current White House administration’s first priority was working class Americans or its own financial gains.

“The common man would say, ‘Well, (President Donald Trump) stands up for me, and he represents me,’” Philpot said. “There is not a person in Quincy who can call him and say, ‘My light bill is getting turned off, Mr. President. I need you to come help me.’ ‘My kids need money for daycare. I need you to come help me.’ There’s no one in Quincy who can do that.

“If you can’t relate to my day to day, whether I have three boats on the river or whether I’m living in the projects — if you can’t relate to my struggle, then what is the point? Why are you in the positions that you’re (in), and what is your motivation? You want to help me? Why? Why do you want to do this job? If people can’t answer those questions, those aren’t people who should be in leadership.”

Philpot believes people who voted for Trump saw him as the answer to their fears.

Pointed criticism of various diversity, equity and inclusion programs by the MAGA flank of the Republican Party have blatantly targeted the legitimacy of Black history in the classroom and transgender people in sports and the military.

Philpot remembers the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell era, when he said he observed several men and women who were “forced to leave the military just for the fact of who they love.”

“You’re entitled to love who you want to love. You know why? Because it’s hard enough to find love anywhere. So wherever you find it — get it, keep it, do what you gotta do,” Philpot said. “They can say, ‘Oh, well, you know, it degrades the cohesiveness of the unit.’ Well, they used to say the same thing about Black people. So, you know, yeah — it’s interesting.”

It would be “fraudulent” if Philpot said he didn’t encounter racial microaggressions in Quincy, but he believes they’re merely a side effect of the community’s lack of diversity.

“When you are isolated and don’t have a lot of exposure to different groups, you draw your own conclusion about how they are, what they’re supposed to be,” Philpot said.

It was a lack of diversity in his own community in the south side of Chicago that fueled him on a curiosity-filled quest to discover what lay beyond the “bubble” he’d grown comfortable inside of.

“I work really hard to become educated, not only about politics, but about the world, the community, the culture,” Philpot said. “That gives me the ability to speak eloquently and be able to share information and outlook that, hopefully, makes them refer less to my Blackness and more to my humanity.”

From the projects of Chicago to the Disneyland of the Gem City, Philpot has indeed made his arrival — and it sounds like he’s here to stay.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.