Letter to the Editor: Adrian is human and changed his mind, rousing the rabble to pick up pitchforks

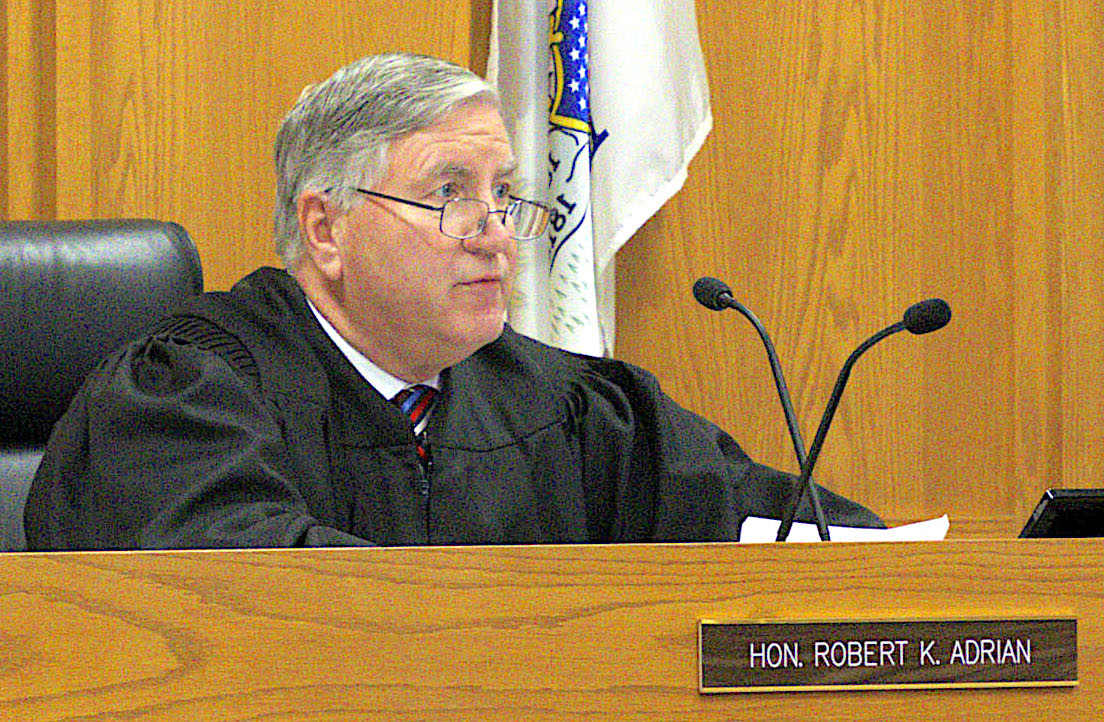

Muddy River News recently published an article detailing the events that led to Robert Adrian’s removal as Eighth Circuit Judge. This letter to the editor will examine the reasoning (or lack thereof) surrounding that removal.

This is not an attempt to assign a value judgment to the sexual assault case People of the State of Illinois v. Drew Clinton 2021-CF-396. Rather, it’s an attempt to examine Adrian’s alleged wrongdoing and the moral and societal implications of him being removed from his position. This letter will attempt to show that Adrian’s removal was not only unwarranted but that the reasons posited for his removal are indicative of a sociological regression in our society.

In October 2021, Adrian found Drew Clinton, 18, guilty of felony criminal sexual assault against Cameron Vaughan, 16, but subsequently vacated Clinton’s conviction on Jan. 3, 2022, and ruled Clinton not guilty based on a lack of credible evidence. Speculative accusations were made that Adrian was motivated to reverse his decision because he thought the mandatory sentencing was too harsh, and these (speculative) motivations were deemed sufficient to remove Adrian from his position as judge.

In the admirable spirit of journalistic integrity and transparency, MRN’s article embedded the legal syllabus for the proceedings against Adrian, providing the public with direct access to what happened.

The article stated the following: “Adrian made statements he knew to be false while testifying under oath before the Illinois Judicial Inquiry Board on April 8, 2022.”

What exactly were these statements and why were they knowingly false? Let’s take a closer look. In the section “Pleadings and Alleged Code Violations,” the syllabus stated:

“And finally, count III of the amended complaint alleged that on April 8, 2022, (Adrian) gave false and misleading testimony when he testified before the Board that he reversed his guilty finding based on a lack of evidence presented in the Clinton case and not because he was trying to circumvent the law requiring the imposition of a mandatory prison sentence upon the defendant. The amended complaint alleged this testimony was false and misleading, and that (Adrian) knew it was false and misleading because (Adrian) reversed his guilty finding in order to circumvent the law, which required (Adrian) to impose a mandatory prison sentence upon the defendant.”

This language is a little obfuscating, but logically, it is the equivalent of saying, “Adrian knowingly lied in his testimony because we think he was motivated to reverse his decision for the wrong reasons.” This is what’s referred to as an untenable argument. It’s unable to be defended logically. Essentially, this language states that “he lied because we think he lied.”

More to the point, it’s presuming to have proof of his motivation, which is impossible for obvious reasons. Conjecture abounds! Moreover, there are certainly reasonable motivations for Adrian to reverse his ruling, the most obvious being his initial ruling was the wrong one.

This sequence of events reflects the virulent norm in society — enforced through the justice system — to moralize motives, which are always speculative. The actual result or consequence of Adrian’s behavior — the reversal of his decision — is that Clinton walked free.

Adrian’s final ruling — finding Clinton innocent — is considered immoral by virtue of Adrian’s intentions. Consequently, it is filtered through the lens of motive-moralization, which is ultimately arbitrary and mutable. Was Adrian’s behavior, reversing his ruling, legally tenable? Yes, it was.

Moreover, based on Adrian’s statements when he reversed the decision, it is perfectly plausible (and probable) that, in addition to rethinking his initial ruling, he thought the sentencing was incongruent — the mandatory sentencing merely mirrored Adrian’s blunder back to him. He knew he made a mistake. These are not mutually exclusive judgments.

He can reverse his decision based on the lack of evidence and, in addition, experience trepidation regarding sending Clinton to prison. From Adrian’s perspective, the mandatory sentencing functionally seems to have cast a spotlight on the lack of evidence in this case, prompting Adrian to reconsider the nuts and bolts, the cold, sober truth. If there was compelling evidence to convict Clinton, Adrian would have had no misgivings about the sentencing.

Adrian is a man of the law. He knows the law inside and out. He knew what the mandatory minimum was before he initially found Clinton guilty. It’s not as if he first learned this after his initial ruling and then chose to reconsider his decision, as if he was somehow newly enlightened by discovering the law for the first time.

He went to law school. He knew what the mandatory minimum sentencing was from the outset, ergo, he genuinely wanted to reconsider the defendant’s guilt based on the evidence presented. Incidentally, the weight of sentencing spurred him to reconsider the evidence (or lack thereof) and the defendant’s guilt — this nuance is absolutely critical.

Adrian’s perspective on mandatory minimum sentencing is incidental. Moreover, this perspective is not a crime. Attorney Drew Schnack successfully proved there was a lack of credible evidence to convict Clinton. There was no smoking gun. If Adrian had found Clinton not guilty to begin with, it’s quite probable that I wouldn’t be writing this letter. Alas, Adrian is human, and he changed his mind. Society loves to moralize those who change their positions while idolizing those who have the courage of their convictions.

In “Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits” (1878), the late German philosopher and value theorist Friedrich Nietzsche wrote:

“…we believe at bottom that no one would change his convictions so long as they are advantageous to him, or at least so long as they do not do him any harm. If this is so, however, it is an ill witness to the intellectual significance of convictions.” (Aphorism 629)

Indeed, Friedrich, indeed.

Intellectual integrity presupposes being able to change one’s beliefs in light of credible evidence to the contrary, regardless of how unpleasant and uncomfortable this process feels. It is the mark of an intelligent, reasonable man to change his mind when confronted with logic that challenges his beliefs. If our leaders all held fast to their errors to preserve their egos and their reputations, society would eventually regress into barbarism.

Furthermore, this moralization of motives is a confusion of cause and effect, creating a slippery slope, as it were. Adrian’s motives were speculatively determined after the fact and erroneously endorsed as his smoking gun.

We might as well dust off the crystal ball and devolve into sorcery if we’re going to speculate on the motives of elected officials and punish them for the morality we project onto these conjured motives. This kind of primeval behavior merely serves to satisfy the bloodlust of a disgruntled public, which doesn’t need to adhere to rationality or credible evidence to be satiated.

On the contrary, revenge is usually irrational, but the vengeful are satisfied by the compensatory eye for an eye. Let’s at least be intellectually honest and call it what it is: the sensationalized media attention this case received (Dr. Phil) served to paint Adrian as the arbiter of the victim’s suffering, rousing the rabble to pick up their pitchforks.

This is what we need to consider before we take it upon ourselves to hurl our uninformed value judgments at Adrian based on emotional reactions to the outcome of one of his cases. After considering the facts, the glaringly obvious conclusion is that Adrian vacated Clinton’s conviction because the evidence against him wasn’t compelling enough.

Indeed, the evidence wasn’t particularly compelling. Attorney Drew Schnack did an exceptional job convincing Adrian of that. As a society, if we slip into the archaic practice of speculating on intentions, moralizing those intentions and then punishing people for them, we are entering perilous waters.

Adrian was within bounds to reverse his decision based on a lack of compelling evidence.

Mitchell Provow

Quincy, Illinois

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.