‘Purely and simply punishment’: Lovelace makes case for resentencing Masters as juvenile to appellate court

QUINCY — Oral arguments in the Gavin Masters appeal before the Illinois Appellate Court Fourth District on Tuesday afternoon focused on the standard of review for a post-conviction petition.

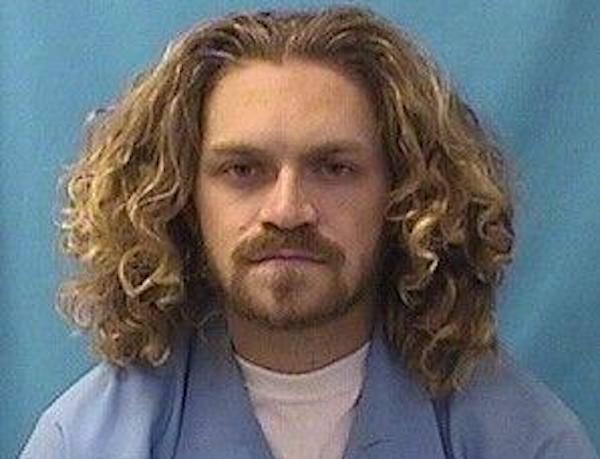

Masters, 26, received a 115-year sentence in the Illinois Department of Corrections in December 2015 after an Adams County jury convicted him of first-degree murder in the July 4, 2015, shooting death of 21-year-old Randy Bowser-Smith and attempted first-degree murder in the shooting of Skylar Osborne, which resulted in paralysis. Masters was sentenced to 45 years in prison on the murder conviction and 20 years for the attempted murder conviction. Twenty-five years was added to each sentence because a firearm was used.

Masters has unsuccessfully filed petitions for post-conviction relief three times in Adams County, with the most recent denial in April by Judge Tad Brenner. Masters’ lawyer, Curtis Lovelace, has argued the sentence was a violation of the proportionate penalties clause of the Illinois Constitution. Lovelace argued Masters, who was 18 when he shot Bowser-Smith and Osborne, should have been considered a juvenile at the time of sentencing.

Tuesday’s arguments were heard via Zoom by Fourth District Appellate Judges Peter Cavanagh of Springfield, James Knecht of Normal and Kathryn Zenoff of Winnebago County.

Lovelace argued for a de novo review, which allows a higher court to examine a lower court’s decision anew without deferring to a previous ruling. He claims Judge Robert Adrian did not sentence Masters, four months past his 18th birthday when the crimes were committed, to rehabilitate him.

“Gavin’s 115-year sentence is purely and simply punishment, and (Adrian) believes that Gavin deserves ‘every second of every minute of every hour of every day that he got,’” Lovelace wrote in a brief to the Appellate Court.

“Gavin asks that this Court not judge him as an adult but instead to truly consider his juvenile characteristics and to recognize that his 115-year sentence is wholly disproportionate as to shock the moral sense of a sensible, reasonable and compassionate community.”

Allison Paige Brooks, counsel for the state, has argued for a review of manifest error — an indisputable error of judgment that is obvious and indisputable that warrants reversal on appeal. She argued in her briefs to the Appellate Court that the postconviction court “correctly found that the defendant failed to meet his burden of showing an as-applied constitutional violation.”

Dr. James Gabarino, a professor in the psychology department at the University of Loyola-Chicago, testified during a March 30 hearing he had interviewed Masters three times by telephone, and each interview lasted approximately one hour. He testified he had Masters complete two sets of questionnaires that included a series of “life history” questions, and he had not made any clinical diagnosis of Masters. He said he had not reviewed the trial transcripts, and he didn’t recall the contents of the police reports.

His testimony was based on his perception of what he said were “five Miller (v. Alabama) issues” that were present in Masters, which were:

- Immaturity and impetuosity, diminished capacity to consider consequences;

- Family and home environment;

- Circumstance of the offense, including the role of peer pressure;

- Impaired legal competency when dealing with the police and legal proceedings;

- Rehabilitation potential.

Miller v. Alabama was a 2012 U.S. Supreme Court case in which the Court held that mandatory sentences of life without the possibility of parole are unconstitutional for juvenile offenders.

Much of Garbarino’s opinion was based on a 10-question Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) test. He said Masters scored a 7 out of 10, which he said was worse than 99 percent of the population.

“Following the evidentiary hearing, the postconviction court thoroughly addressed the myriad reasons why it gave little weight to the evidence presented through the report and testimony of Dr. Garbarino related to the Miller v. Alabama factors that allegedly pertained to (Masters),” Brooks wrote.

“Dr. Garbarino did not provide a specific factual basis for an opinion about (Masters) having been impulsive. Dr. Garbarino found it difficult to know how viewing gory images or playing a violent video game affected (Masters). Dr. Garbarino did not indicate the severity, frequency or recency of domestic violence in the home.”

Zenoff noted that Brenner said in his decision that he couldn’t give “significant weight” to the results of Garbarino’s ACE test because the lack of information it had regarding the questions and that the responses were not independently verified. She asked Lovelace during Tuesday’s hearing where Brenner’s error was made.

“Well, it’s indisputably wrong,” Lovelace said. “(Brenner) said (he) couldn’t give significant weight to the ACE because (he) didn’t know the questions. That’s just not true.”

“I think the record shows there was a general description of the questions, rather than, ‘This was the question. This was the answer,’” Zenoff said.

“The record reflected that when asked, Dr. Garbarino testified as to the specific area, the type of questions,” Lovelace said. “No, he did not verbatim give the questions, nor did the court, nor did the state on cross-examination, request, the specific questions.”

Zenoff also said Brenner was concerned that neither Garbarino’s report, nor his testimony at his March hearing considered any information from the trial transcripts. She asked Lovelace what that wasn’t a valid concern.

Lovelace said Garbarino acknowledged the facts of the case. He said Masters was handing out with friends in a house where there was an attempted sale of marijuana. Bowser-Smith tried to grab the marijuana and Masters shot him, and then he shot Osborne.

“There isn’t an issue with regard to what happened in the case,” Lovelace said. “What does it matter that (Garbarino) didn’t review the testimony as to what happened in the case?”

Brooks wrote that the defendant’s sentence was proportionate to his severe crimes, citing the 2018 case of People v. Pittman. She wrote that the 18-year-old offender in that case had a history of experiencing and witnessing domestic violence.

Lovelace disagreed.

“Mr. Pittman was convicted of killing his 17-year-old girlfriend, her mother and her 11-year-old younger sister,” Lovelace wrote. “(The defendant) stabbed his girlfriend 19 times, strangled her and fractured her jaw. He stabbed her mother, who was on crutches, numerous times. He stabbed her younger sister 29 times. This case is clearly not analogous to Gavin’s case.”

Lovelace said Masters filed a motion to reconsider in 2019, asking Adrian to honor the Illinois Supreme Court’s ruling in People v. Harris, recognizing that an 18-year-old defendant can make an as-applied constitutional challenge for a de facto life sentence. Adrian denied that request.

“There’s no doubt that the circuit court in Adams County has had some reluctance in embracing the Illinois Supreme Court’s holding in People v. Harris,” Lovelace said during Tuesday’s hearing. “That’s why we’re here for the third time. Based upon my experience with this court, as well as the language, I think the court continues to struggle with applying the law in this case.”

Brooks told the Appellate Court judges most of the record supports Brenner’s ruling and that the case is “straightforward.”

“This is just a completely shocking and violent crime,” she said. “This is the type of thing where being a personal perpetrator of such a serious, violent crime, it makes it wholly distinguishable to the other sorts of cases where an already 18-year-old defendant was convicted by accountability.”

Zenoff asked Brooks about Lovelace’s observation that Brenner seemed “very reluctant” to acknowledge the Miller v. Alabama factors applied to Masters.

“Miller is the standard for defendants who are under 18 at the time of their offense,” Brooks replied. “It’s not applicable to the defendant here.”

Brooks went on to say that if Masters claimed he had witnessed some domestic violence and relied on his adverse child experiences, “that’s a very small part of the case. It’s not going to make a big difference in terms of what the seriousness of his crimes are. … The defendant’s upbringing was not that atypical. It’s not a situation where it was an extreme case of poor upbringing.”

Knecht interrupted Brooks.

“You use the phrase like, ‘It wasn’t atypical,’” he said. “No marriage. No (parents) living together. A stepfather who’s in jail for meth delivery. (Masters) begins using drugs at age 10. I don’t see that that is anything other than atypical.”

“It’s not so extremely atypical that it’s going to overwhelm the facts and circumstances of the crime and just make the court disregard everything else in the case,” Brooks said.

The decision from the three judges will be posted on the Illinois Supreme Court website the same day it is issued.

The Fourth District Appellate Court is in Springfield and hears cases appealed from trial courts in 41 counties, including Adams, Pike and Brown.

Lovelace, who grew up in Quincy and previously worked in the Adams County State’s Attorney’s Office, now lists the Center for Criminal Law & Justice in McKinney, Texas, as his employer.

Miss Clipping Out Stories to Save for Later?

Click the Purchase Story button below to order a print of this story. We will print it for you on matte photo paper to keep forever.